God is the perfect artist. He creates beauty at every scale and in every context we’re willing to find it. Our job as cooperators in his creation is to represent that beauty to the world… and that’s hard. Every earthly artist is going to struggle—that’s the nature of attempting anything good. What a joy it is, therefore, having the job of helping our sons push through that struggle and find the satisfaction of co-creating through art. This has been a passion of mine which unites the various steps in my career from advertising to architecture to homeroom teacher. Having taught art for a decade now, I’ve heard from many parents eager to foster their son’s skills and appreciation of art.

A quick table of contents if you want to jump to a specific question:

- Why is art required?

- How can I help my son be more invested in art?

- How can I help my son take it to the next level?

- What do you recommend for the summer?

- How do you grade a student’s art?

- If I’m not good at art, how do I help my child?

- What is the point of doing projects?

- What books can you recommend?

- Why focus so much on drawing?

- What is your most common advice to students?

- What is your main goal as an art teacher?

On that note, let’s get to the questions:

Why is art required?

We believe that studying art is an essential element in a true education, not an interesting tangent. The skills your boys learn through our art curriculum transcend technique and design. Our primary aim is to develop his ability to observe. Seeing accurately is prerequisite to appreciating beauty and is an ability best learned through the rigors of artistic reproduction. Both the mundane and the exceptional—a clay pot or a breathtaking landscape—provide opportunities for training our eyes and our heart to be open. For example, I often point out when doing self-portraits that the difference between good and excellent comes down to tiny adjustments that are only possible through looking at every feature as if for the first time. What makes your mouth or eye or nose look distinct from that one? A small curl here, narrowing there, shadow and light where you don’t expect them.

These lessons train the boys in more than just art. The mental discipline, of course, is a worthy end. The physical skills of manipulating media and artistic tools is helpful. Like in any other subject, some boys will struggle more than others. We all need to struggle a little! But foremost, the student of art attains a greater openness to all the transcendentals—the true, the good, and the beautiful. There is truth, and in art class, it is right in front of them. There is beauty, and capturing it begins with a capacity to accurately render reality. As for goodness, perhaps a quote from Tolkien best captures this: “There is nothing like looking, if you want to find something. You certainly usually find something, if you look, but it is not always quite the something you were after.”

How can I help my son be more invested in this class?

For many boys, tapping into their natural interests is the most important victory. Cars, planes, warriors, animals… this is a good list to start from! If sports are his thing, finding images of his favorite athletes might pique his interest. Anybody is going to be more attentive to the details if the subject is personally interesting. If your child becomes interested in drawing on his own time, the more challenging exercises in class may seem less onerous.

How can I help my boy take it to the next level?

Don’t underestimate the benefits of good quality materials. Poor materials can frustrate your budding artist with unnecessary limitations. Sketch paper, for example, is intended for quick sketches or studies and will disintegrate if worked up into a tightly composed drawing. Mixed media paper, for example, can be used for pencil, pen, marker, and paint. Decent quality colored pencils, such as Prismacolor Scholar, are essential for producing good drawings in that medium. Cheaper brands use less pigment resulting in insipid colors and poor blending.

Novelty can also be your ally. Drawing on black, gray, or brown toned paper can spark some creative ideas. Are you feeling ambitious? Sculpey clay can be baked in a standard oven—or even blasted with a heat gun—and then painted. Some students who struggle with drawing produce remarkable work in sculpture.

What do you recommend for the summer?

The summer is a great time for diving deeper. You usually have more flexibility and can tackle more involved projects. Perhaps this is when you try that sculpture project? Museum trips are a fantastic way to expose your child to the heights of artistic achievement. This is exactly what artists have done through the ages: study and copy the masters. Of course, you don’t have to restrict it to art museums: there are plenty of items of interest at history and natural history museums. Nature centers usually have quality taxidermy specimens that are a great challenge. If architecture interests him, you can venture into the city or sit on the curb of your favorite suburban neighborhood to draw.

How do you grade a student’s art?

Although there is an expressive, subjective element to art, a major component is the objective degree of accurate representation. When grading any student’s art, the objective accuracy of their work, weighted by their general ability, is my main consideration. Some work we do in class allows for their artistic interpretation or adjustments to an original which I assess more generally. For example, sometimes they copy a simple line drawing and then add color of their choosing. I typically coach them on how to use color effectively, but it’s their choice. When using pastel, some boys instinctively blend colors smoothly while others prefer a more painterly or impressionistic application of the color. The objective reality of the color present (which can sometimes be surprisingly open to interpretation) is as important as the forms and shadow shapes. Add to that the complexities of composition—how they arrange the subject on the paper. It is not uncommon for me to have a student start over if they are starting too small, leaving huge amounts of blank space on the page. Other times, I work with the boy afterwards to trim the page to a good shape and size.

Because of the many considerations that the student has to weigh in doing any of our class work, it is rare that I cannot find aspects that they have done well when assessing their work especially because I do my rounds of the classroom and coach them through the process.

If I’m no good at art, how can I help my child?

The two main ways that any parent can help are with encouragement and personal experience. Although you may feel incompetent, it’s best not to make a big deal of your lack of skill—children feel, often incorrectly, that their talents can’t differ much from those of their parents and therefore putting yourself down will take the air out of your kids’ sails. Be upbeat about the possibility of them learning a new skill! Furthermore, by sheer years of experience, you have far greater knowledge of art, artists, and even art techniques. You are certainly a more competent researcher and can help connect your child with good sources.

What is the point of doing projects?

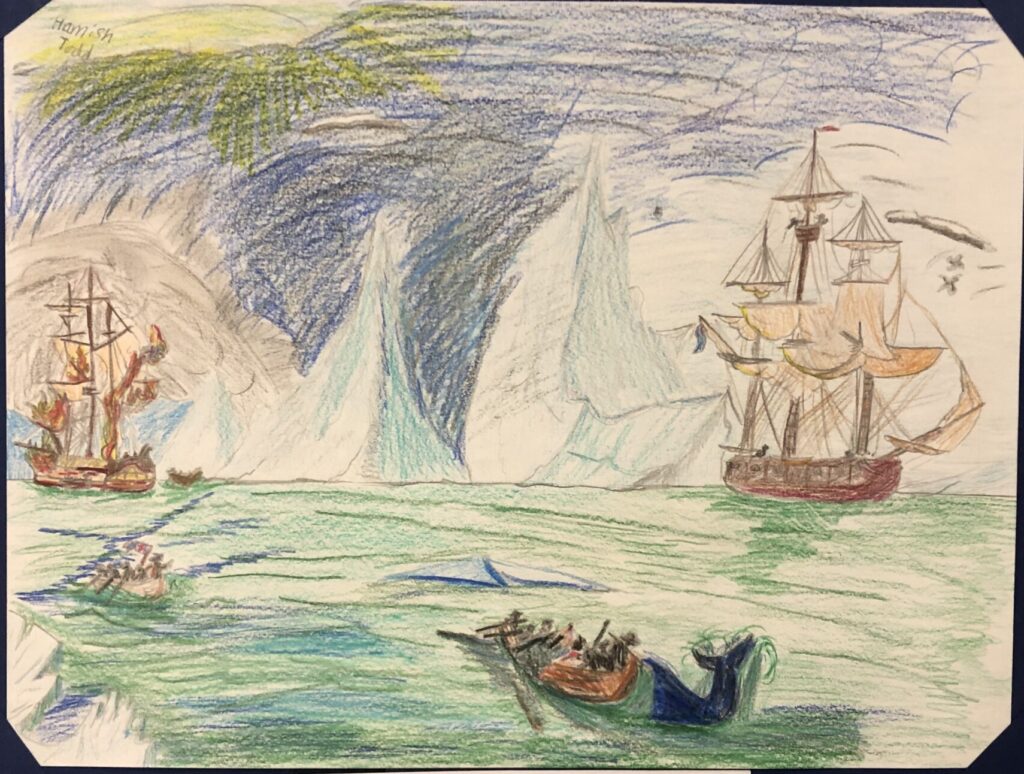

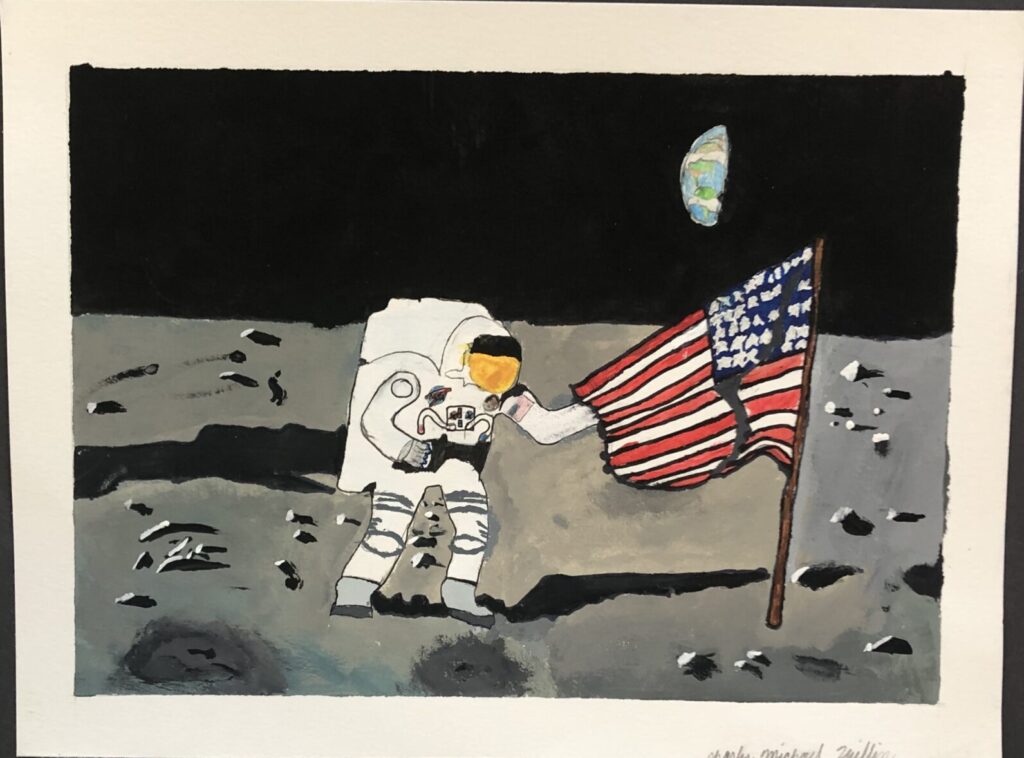

Although I assign no homework in art on a regular basis, there is something very important about creating art completely on one’s own. Years ago, when one of my colleagues and I first assigned an art project, we selected about a dozen of our best students and gave them the option to create a Christmas-themed work on their own. We quickly realized, however, that we were underestimating the potential of all our students to create good art. Time and again since then I have seen the proof that the boys will surprise you and themselves. Whether or not they “win,” so many great works have been created—and not only by those boys everyone expects.

The themes we choose help to give some parameters while leaving room for a wide range of interpretations. And even the best artists know that a commission and a deadline really help kick us into high gear!

What books can you recommend?

Besides the age of your child, the most important factor in answering this question is what goal you want to achieve. If you are hoping to spark his interest in doodling and drawing for fun, I have fond memories of using Ed Emberley’s drawing books as a kid. If you are looking for supplementary art activities to fit with a particular interest, the Dover coloring books are wonderful for any age and nearly any subject. There are countless books on technique out there and most of them demonstrate how to progress from simple lines and geometric shapes into detailed drawings. Ruth Sanderson, the illustrator of several of my family’s favorite picture books, has one for drawing horses. John Muir Laws has an entire method for drawing birds from a nature journaling perspective. I recommend that you find artists whose work you admire and find out if they have tutorials—or simply buy a book collection of their work. Years ago, I stumbled across the artist James Gurney, and now he has published numerous books that would interest many an imaginative child! Of course, a museum exhibit book or coffee table book focusing on a great master (perhaps Rembrandt, Homer, or Payne, to name a few) can provide immense inspiration.

Why do you focus so much on drawing?

Drawing is the skill upon which all of the other visual arts depend. It is standard practice for a painter to do a series of “studies” before embarking on any major painting. Sculptors often draw the subject of their sculpture from various angles to warm up to the challenges of creating in three dimensions. Architecture, of course, is intrinsically linked to drawing as it relies on drawings to capture precisely what should be built. Even film directors rely on artists to draw storyboards to capture the setting and mood of their film.

In teaching students technique, they will have to work through the physical difficulties of producing a clean, smooth line and the mental difficulties of filtering out what they think they see. There is the physical difficulty of training their eye to observe angles and curves and the mental toughness to try again.

Furthermore, drawing is a skill with far broader applicability. Although it is fun to experiment with various media—which we do—drawing is the skill that will serve all of these boys in the future. Even if your sons don’t pursue art to the AP level… or the college level… or the professional level, they will obtain a proficiency that belongs in the liberally educated man’s repertoire so that he can turn to art in his leisure with confidence that his work is an image of the true.

What is your most common advice to students?

“Draw, don’t write”: By far the most common error my students make is drawing too heavily. I reiterate daily the need to work lightly because mistakes are guaranteed for all of us. I try to develop their ability to hold the pencil farther back from the tip as if holding a paintbrush. After all, they’re drawing, not writing. This helps prevent a heavy touch and also allows a better view of their lines as they’re drawn.

“Add, then subtract”: When making corrections to a drawing, it’s usually better to add the correct line so that they have their previous line as a point of reference. Only after the correction has been made should they erase the mistake. This process may take a few goes.

“Small corrections”: Building on the previous point, In nearly every drawing, the difference between good and excellent is in small adjustments. This is quite noticeable when doing perspective or architectural drawings. Why does that column look “off”? Perhaps one-eighth of an inch here or there. If the road you’re drawing misses your vanishing point by one-sixteenth of an inch, you can tell. Working on small corrections will set your work apart.

What is your main goal as an art teacher?

My goal is to instill in my students, through a foundation in strong artistic technique and careful exposure to beautiful art, a greater joy in the created world.

As G. K. Chesterton put it, “The world will never starve for want of wonders; but only for want of wonder.”