Sections

Reimagining Risk

The following essay is part of an ongoing series in which Dr. Joseph Lanzilotti surveys and summarizes the ever-growing body of research on boys’ education.

“To love is to risk not being loved in return,

To live is to risk dying,

To hope is to risk despair;

To try is to risk to failure;

[T]he greatest hazard in life is to risk nothing. (…)

Only a person who risks is free.”

—William Arthur Ward (1921-1994), excerpt from “To Risk” [1]

“Personal involvement often requires risk. Risk implies danger. To face danger demands courage. This is why the fearful are seldom involved.”

—William Arthur Ward [2]

All life involves risk. To be alive in this world is to be vulnerable to a plethora of dangers. If I step out my front door, I may twist my ankle on the way to my car. And, in fact, not to act contains its own risk. To aim to live in such a way that it is impossible to have negative outcomes is not only foolish but actually, and perhaps counterintuitively, a dangerous way to live. Not to take reasonable risks is itself not simply risky but can cause grave harm physically, spiritually, and psychologically. Healthy risk-taking opens the door to much greater rewards while foolish risk-taking can lead to absolute ruin.

The Problem

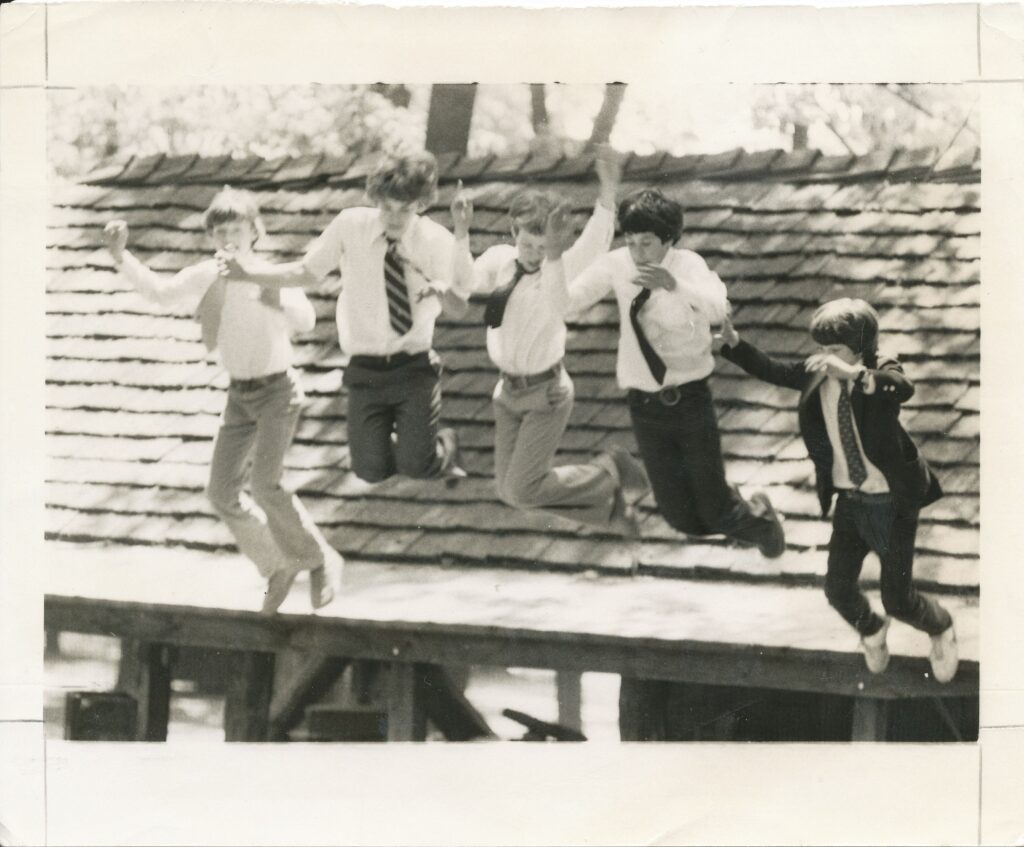

Over the past several decades, researchers have confirmed what many of us have noticed in the broader context of our culture. Children are spending less time outdoors and, when they are outdoors, their time and activities are highly managed by adults whose goal is primarily safety. We want our children to be safe. However, due to a host of factors, safety has become not merely a goal but the goal above every other goal. Jonathan Haidt in his book The Anxious Generation calls this debilitating ideology “safetyism.”[3] Because of safetyism, children are discouraged from taking risks which generations ago were seen as a normal part of growing up. Climbing trees, jumping off rocks, exploring gulleys and ravines, and running over tangled roots, for example, have been a normal and healthy part of childhood. And yet, with fewer and fewer opportunities given to children for unstructured play outdoors, these risks cannot be taken. Helene Guldberg recounts these observations in her book, Reclaiming Childhood. Many parents, she says, are restricting and thwarting healthy independence for their children in the name of safety.[4]

There are a number of experts in the fields of psychology, educational theory, and neuroscience who have been working to identify the changes that have occurred over the past several decades which have strong correlations with anxiety disorders and other mental health problems. Psychologist and researcher Dr. Peter Gray is among these experts. He writes, “Somehow, as a society, we have come to the conclusion that to protect children from danger and to educate them, we must deprive them of the very activity that makes them happiest and place them for ever more hours in settings where they are more or less continually directed and evaluated by adults, settings almost designed to produce anxiety and depression.”[5]

Gray relates that, since the late 1950s and early 1960s “in the United States and other developed nations, children’s free play with other children has declined sharply. Over the same period, anxiety, depression, suicide, feelings of helplessness, and narcissism have increased sharply in children, adolescents, and young adults.”[6] Gray laments that in an effort to protect our children we have inadvertently created the perfect recipe for anxiety and depression. We have done this by depriving children of the freedom and time to play outdoors, with friends, in settings that allow them to naturally and freely challenge themselves, work together to overcome challenges, and to experience the joy of living in a world in which uncertainty of outcome is not a debilitating hurdle but rather a thrilling impetus towards more abundant life.

A New Field of Research: The Benefits of Risk

In January of this year, 2025, Nature Magazine published a piece titled “Why Kids Need to Take More Risks: Science Reveals the Benefits of Wild, Free Play.”[7] The article provides an excellent survey of a burgeoning field of research on the benefits of risk and the dangers of trying to protect children from it. In recent decades, several researchers have worked together to study “risky play” and its benefits to children. Among the most notable expert researchers in the field of risk and child development is Dr. Ellen Beate Sandseter who has collaborated with several different researchers throughout the world in recent decades to study and address the problems facing children and risky play.

In 1996, Norway passed legislation which aimed at making play areas safer for children. Playgrounds throughout Norway were stripped not only of potentially hazardous elements; they were being completely redesigned in ways that thwarted the possibilities for children to take healthy risks while at play. And, ironically, studies have shown that these playgrounds did not actually result in fewer injuries to the children that legislation had aimed to protect. Dr. Sandseter set out to study the broader effect the well-meaning but apparently ineffective law affecting children’s playgrounds was having on children. Through her research, she found that the safer equipment and spaces didn’t inspire children’s curiosity and creativity. Children were looking for challenges and were finding spaces which were artificially uninteresting and unchallenging. Moreover, Sansetter found that as they grew up, adolescents who were deprived of positive and healthy opportunities for risk were more likely to take dangerous and unhealthy risks.[8]

Dr. Zaneta Thayer, associate professor of anthropology at Dartmouth observes, “One of the ironies of modern parenting is that our children have never been physically safer and yet we have never been more worried about them.”[9] In a 2024 paper, Dr. Thayer was a member of a team of researchers that advocated for a return of monkeybars to children’s playgrounds. Playgrounds are an easy target for a risk-averse society, not because they are a primary or leading cause of injury (which they are not), but because they are perceived to be potentially dangerous. Children playing freely can make adults, particularly female caretakers, extremely nervous. Studies have shown that women are more risk averse than men.[10] While a woman’s natural instinct to protect is good and beneficial, especially when caring for infants and toddlers, it can restrict the development of older children, especially young boys. On the other hand, a man’s penchant for taking risks can be excessive if not checked and balanced by a woman’s perception of danger. There truly is a profound complementarity at work here for the upbringing of children, and both parents are wise to be conscious of their respective tendencies.

Despite the fear and worry around free play on playgrounds, a 2003 study calculated the risk of playground injury at no more than 0.59 injuries for every 100,000 uses, which is far less than the rate of injury through organized sports.[11] In youth soccer, for example, the rate of injury is around 2,000 injuries for every 100,000 hours of play.[12] And yet, because of its perceived dangers, free play in interesting and challenging settings is in danger of being lost for many children. This is both because of the perceived dangers of free play and ignorance of its benefits for children.

An essential part of the response to safetyism is advocacy for what researchers call “risky play.” Its benefits are so well-documented that even safety experts are advocating for it. Among these is Pamela Fuselli, president and CEO of the injury-prevention non-profit organization Parachute, based in Toronto, Canada.[13] Fuselli, who has over twenty years of experience in injury prevention, says we cannot underestimate the value of risky play because the “benefits are so broad in terms of social, physical mental development and mental health.”[14] Her advocacy does not ask parents to throw safety concerns aside; rather, they are asking parents and educators to contextualize these concerns within the broader context of children’s needs and to become aware of real vs. imagined dangers. Taking the right kinds of risks can actually reduce serious injury.

Fuselli does not say this lightly. She advocates for prevention of serious injury because of how common preventable injury is among young people. Parachute, her non-profit based in Toronto, Canada, aims to help parents, children, and educators discover how to prevent serious injuries before they happen. In a podcast episode titled “Keeping Kids Safe, Not Bubble-Wrapped,” she talks about the need for children to be given freedom to explore and learn through risky play while parents and educators work together to protect them from real danger and preventable serious injury. This is a common theme among those who are studying and advocating for more “risky” play. Far from throwing caution to the wind, they are simply saying that, too often, parents and educators today work against human nature and against its flourishing by preventing children from engaging with the world in ways that are exciting and challenging. Rather than saying no to a group of boys who want to play in a creek bed, advocates of risky play would have us assess the risk, the possible injuries or other negative outcomes, considered in proper proportion with the benefits.

According to Fuselli, Parachute exists because preventable injury is the leading cause of death “if your loved one is between the ages 1 to 44.”[15] If we look at the difference between boys and girls in these statistics, a troubling, though predictable outcome is found. According to Dr. S. George Kipa, “Men are twice as likely than women to die from an unintentional injury.”[16] Men are more likely to take risks and to suffer physical injury from these risks. Likewise, they are more likely to work in careers which have greater hazards than women. For these reasons, they are ten times more likely to die in a work accident.[17] An important aspect of risky play for boys is providing an environment where they are free to take reasonable, responsible, and prudent risks which allow them to experience the thrill of life. Although more research is needed in this field, there are good reasons to hypothesize that more risk taking by boys will make them more aware of their limits and the real consequences of actions which may result in injury. For those who are prone to be overly exuberant in taking chances, this may lead them to be more prudently careful in the future. For those who are more hesitant in taking risks, small and incremental opportunities for taking risks may lead to unexpected and surprising advances when sustained over the course of a primary, elementary, and secondary education. Consistency is key for making this kind of progress as it would be with other forms of literacy. A study recently found that risky play, which results in greater physical literacy, contributed to a decrease in injury in sports.[18]

As previously noted in the study of caregivers, boys are more likely than girls to take risks. They are going to take the kinds of risks during play that are going to make parents and educators want to make things not merely as safe as necessary but as safe as possible. And, in doing so, a boy’s natural need for movement and risk-taking will be thwarted. In a mixed setting, the boys will receive most of the correction from well-meaning but often misguided and misinformed supervisors who perceive greater dangers than are actually present. Curtailing boys’ opportunities for healthy risk is exactly the wrong approach. Allowing boys to climb trees, engage in rough and tumble play together, and explore interesting natural environments all contribute towards channeling and directing their natural need for thrill and adventure, a need that is quantitatively higher for boys than for girls. Mr. Alvaro de Vicente, headmaster at The Heights, gives the following advice for those of us who are entrusted with the care of boys as parents or teachers: “For boys, it is best to be relatively lenient with physical risks and to exercise more caution with intellectual and moral risks. In other words, let your son do things in which he may experience some bodily pain or discomfort (to a certain extent, obviously), but be careful in letting him do things that could warp his vision of other people and entangle him in addiction.”[19]

In 2019, the Board on Children, Youth, and Families at the National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Technology reviewed the current landscape of adolescent risk behavior and found that “most theorists agree that risk taking during adolescence is normal, but that the key to healthy risk taking is to provide guidance in decision making and to encourage adolescents to engage in less dangerous and more constructive risks.”[20] As they grow into young men, boys have a greater proclivity toward more hazardous and harmful risk-taking—for example, failing to secure a seat belt when riding in a car, driving at high speeds, and being more likely to drink and drive. As a boy matures, the role of parents, teachers, and mentors is essential in helping to guide him as he matures so that he can be encouraged to take the kinds of risks that will lead not to his harm but to his growth and flourishing.[21]

As parents and mentors we ought to be having conversations with the children under our care about positive risk taking. Dr. Barbara Morrongiello, at University of Guelph in Ontario, Canada, says, “Parents and teachers who [integrate] conversations about risk-taking into their daily lives may have long-term sustained effects on children’s attitudes toward risk.”[22] As children grow into young adults, we can help them to reflect upon the ways in which they have taken those risks which helped them to grow. We can also help them to identify the difference between risk-taking that leads to more life in comparison with recklessness and rash imprudence.

Saying Yes to Risky Play

When it comes to risky play, Dr. Ellen Sandseter’s definition is the most widely accepted. She defines risky play as “thrilling and exciting play that involves uncertainty and a risk—either real or perceived—of physical injury or getting lost.”[23] Eight categories of risky play have been identified:

- Play with great heights—danger of injury from falling, such as all forms of climbing, jumping, hanging/dangling, or balancing from heights;

- Play with high speed—uncontrolled speed and pace that can lead to a collision with something (or someone), for instance bicycling at high speeds, sledging (winter), sliding, running (uncontrollably);

- Play with dangerous tools—that can lead to injuries, for instance axe, saw, knife, hammer, or ropes;

- Play near dangerous elements—where you can fall into or from something, such as water or a fire pit;

- Rough-and-tumble play—where children can harm each other, for instance wrestling, fighting, fencing with sticks;

- Play where children go exploring alone, for instance without supervision and where there are no fences, such as in the woods;

- Play with impact—children crashing into something repeatedly just for fun; and

- Vicarious play—children experiencing thrill by watching other children (most often older) engaging in risk.[24]

Each of these are relative to the age, competencies, and abilities of a particular child. For a two-year-old boy, a “great height” might be an 18-inch high platform off which he jumps gleefully.

Dr. Peter Gray contends that these kinds of play (freely engaged without the direction and constant intervention of adults) help children to “(a) develop intrinsic interests and competencies; (b) learn how to make decisions, solve problems, exert self-control, and follow rules; (c) learn to regulate their emotions; (d) make friends and learn to get along with others as equals; and (e) experience joy.” He goes into great detail for each of these benefits.

The last of the benefits Gray lists is the experience of joy. I would argue that this is the most important and yet most overlooked positive outcome of allowing children to engage in free outdoor play. Joy can’t be made or produced. It arises from the depths of the heart in response to the goodness of things and in response to a fulfilled hope. When a child sets out to do something new, he always does so in hope that it may turn out for the best. Even when, for example, jumping across a small brook results in wet socks, this slight failure can turn to joy at the thrill of having tried to do something which tested their limits—or at just how funny and fun it is to get wet by falling into some shallow water. Dr. Sandseter relates that when she interviews children about their experiences of engaging in risky play, they call it “scary-funny,” a kind of “scary joy.”[25]

Sandseter’s work is complemented in large part by that of Dr. Mariana Brussoni, Professor and Director of the Human Early Learning Partnership at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada. Her work greatly informed Jonathan Haidt’s writing on the need for outdoor play in his book The Anxious Generation. Haidt writes, “Mariana quickly joined my pantheon of experts on play, along with Lenore Skenazy and Peter Gray. With articles such as Play Worth Remembering: Are Playgrounds Too Safe? and Risky Play and Children’s Safety: Balancing Priorities for Optimal Child Development, Mariana makes the case that we harm children’s social, physical, and even immune development when we remove all risk from their lives.”[26] Studies show that boys, in particular, crave the experience of risk, and may seek it in increasingly dangerous or erratic ways if denied the proper channels.[27]

And it’s not only children who may be able to benefit from a change in mindset and embracing a way of life that involves more daily risk. While this is an area of research which is underdeveloped at the present time, Sandseter hypothesizes that adults can also experience the childlike joy which comes from engaging in the real outdoor world in ways that are risky in all the right ways. This kind of joy can permeate our entire lives when we realize that we don’t have to cower in fear before risky situations and challenges. When we see them as opportunities to grow and develop our competencies, we can likewise experience the outcome as joyful fulfillment when we accomplish what we set out to do. Likewise, we can grow in resilience and in the virtue of fortitude when we don’t immediately obtain the results that we desire. Each day can be a source of joy before the adventure of life when lived with the spirit of a child fully alive.

There are a number of other researchers whose work is contributing to the support for risky play. Among these are Helen Dodd (a child psychologist at the University of Exeter, UK), Eva Telzer, Jean Twenge, Kayt Sukel, and Dr. Gever Tulley (founder of the Tinkering School and author of 50 Dangerous Things You Should Let Your Children Do).

Why “Risky”: Some Semantic Misunderstandings

Because of growing risk-aversion in the prevailing culture, some advocates of risky play have preferred to substitute the word “adventurous” for “risky.” While this way of describing risky play is somewhat adequate, Dr. Ellen Sandseter, believes that something essential is lost when we use a word which doesn’t carry within it the possibility of loss. According to her, “it’s actually an important point that the meaning of the term also includes the possibility of a negative outcome—since the fear of this outcome is the reason we have all the restrictions and surplus safety in the first place.”[28] Sandseter says, “Our very clear message should be that children’s risky play (yes, risk (!) but in a playful and relatively safe context) most often leads to positive outcomes; exciting experiences, development, learning, mastery….”[29]

Researchers are finding that when children are encouraged to take healthy, positive risks, they are less likely to take negative, unhealthy risks. There is also a correlation between risky play and overall emotional and psychological well-being. We cannot avoid risk. However, the risks we encourage, allow, and facilitate can either help or hinder the flourishing of the children in our care. If we do not encourage risks that will lead to growth and flourishing, we risk losing our children to merely a different path of risk-taking which will be to their detriment and perhaps even their own self-destruction.

Many people still think of risk mainly as an account of what might go wrong in a situation, but the understanding of risk in the field of child development has broadened. In a 2022 article headed by Sandseter, the authors write, “[A]fter 2010, the discourse was addressed more as future uncertainties. This change of discourse opens towards a recognition of the necessity to sometimes take a risk to achieve a positive result and thus a preference for risk-benefit assessments over only risk-reducing measures.”[30]

Risk comes into play whenever there are actions that are taken with some desirable goal in mind and which necessarily may result in not obtaining our desired end. This is usually accompanied by the possibility of some other undesirable outcome. Risk involves an action in which there is a known and foreseen possibility of loss, however great, and at the same time, a known and foreseen possibility of gain. Risk is not only tolerable but necessary for human flourishing and ought to be thought about positively by parents and other educators. At The Heights, we aim to encourage parents, teachers, administrators, and educational institutions to reexamine their preconceptions regarding risk and to seek ways to encourage healthy risk-taking in age-appropriate ways. Much of this is facilitated rather than directly managed or controlled by teachers and parents. It is facilitated by allowing children to play like children in environments and ways that open the possibilities for risk. Helping our boys to face up to their fears and overcome them in a healthy way is an essential part of their education.

Yet the term “risky” is also distinct from “hazardous.” Advocates and facilitators of risky play should acknowledge the very real concern of serious injury that can result when children play. One group of researchers helpfully defined the difference: “A risk arises in situations where a child can recognize and evaluate the challenge and decide on a course of action based on personal preference and self-perceived skill. For example, how high to go on a climbing structure or how fast to run down a slope. A hazard is posed by situations where the potential for injury is beyond the child’s capacity to recognize it as such or to manage it. For example, an improperly anchored slide could topple under a child’s weight, or a rotten tree limb may break.”[31]

For each category of risky play, it is the responsibility of adults to ensure that the space in which children are playing is free of true hazards, especially those which children may be unable to recognize. This could mean assessing a tree’s health and removing rotting limbs that are in danger of falling under a child’s weight. It may involve removing litter or hazardous debris, keeping equipment in good condition, or encouraging the children to wear shoes in certain environments. Sometimes, we identify hazards that cannot be removed but which can be made obvious with a cone or other sign which alerts children of the dangers. Such signs are common on ski slopes for advanced terrain, which allows for a healthy dose of risk for experienced skiers and snowboarders but represents a true hazard for those who lack experience. Similarly, certain play areas may reasonably require boundaries, especially for younger children. These boundaries can be expanded as the child grows in competency.

What Parents Can Do

Researchers of risky play are finding that, by and large, children are very good at assessing their own capabilities. The transition from cradling a baby to allowing a toddler to take his first few steps outside can be frightening for new parents. With risk of scrapes and bruises comes the great hope of freedom, the freedom to walk on one’s own two feet, to run like the wind across an open field, the freedom to test one’s limits. Moving from coddling to facilitating involves prudence. Before moving forward it is necessary to distinguish between risk and hazard. It is our responsibility as educators to foresee dangers of which children may be oblivious and to protect them from these dangers.

Too often, adults see dangers everywhere in the realm of the physical, real world—but are oblivious and blind to the dangers of the virtual world of screens and other electronic devices. In his book The Anxious Generation, Jonathan Haidt makes the compelling argument that “overprotection in the real world and underprotection in the virtual world” is doing great harm to an entire generation of young people.[32] According to Haidt and many others studying the rise in anxiety and self-harm disorders, we have actually measured the danger backwards. The gravest and most present danger to many of our children comes from the virtual world and from a failure to engage meaningfully with the real world. We ought to be encouraging the taking of reasonable risks in the real world while educating ourselves regarding the unreasonable risks associated with giving mere children unfettered access to the internet with a personal computer (read “phone”) placed within their hands.

A parent’s duty will inevitably shift over time as their child encounters new environments, physical and digital, and gradually becomes more independent. When our children are young, we must be directly involved in preparing their environment to remove those clear and present dangers to life and limb. Our duties as parents with little ones who are absolutely vulnerable is to protect them from danger. As they grow, it is our duty to ensure that they are willing and able to take the risks necessary for their development and growth.

This is analogous to what we do in agriculture where seedlings are nurtured first in greenhouses to protect them from the pests and weather events which could easily destroy them and from the weeds which would choke them off. A greenhouse is a protected (but not sterile) environment meant to reduce the hazards to young and vulnerable plants. But in order for these plants to survive in the outdoor environment, they will need to be slowly and intentionally acclimated to their harsher and more challenging environment. A prudent botanist will know what species can withstand what conditions and how to allow for this transition in which temperature fluctuation will be much greater, the sun’s rays will fall on the leaves with greater intensity, and gusts of wind will test the strength of the plant’s stem. If the plants are encouraged, so to speak—if they are exposed to the more challenging conditions in an incremental and methodical way, with prudence—they will not only survive but will be hardy and resilient for the years ahead.

Raising Wise, Courageous Risk-Takers

Our headmaster, Alvaro de Vicente, has spoken in the past about the hope and the mission to form “wise, courageous risk-takers” of the boys who pass through The Heights.[33] Why would it be our goal and aim to encourage boys to take risks? This all comes down to the vision of what we are and what we are made for. As Alvaro has said, there is more to life than merely being alive. To be fully alive is to learn to take the risks that bring ourselves and others more abundant life, the life of Christian service and witness. Jesus tells us that the Christian way is a way of risk. He tells us that whoever wishes to save his life will lose it, but whoever loses his life for His sake will find it (cf. Matt. 16:25). Setting off after Christ is risky business, yet it is the adventure that comes with the greatest reward. There will be no life unless we are willing to lay down our lives and our own agenda and live for Christ and His Kingdom.

When we allow and encourage our boys and young men to become wise, courageous risk takers, they gain even when a particular action doesn’t result in the desired gain. The habit of taking courageous and wise risks actually helps to form the virtues necessary for men who will become and remain fully alive. How will young boys become the kind of men who are willing to forget what lies behind and press on towards greater heights if they are not able to practice overcoming small obstacles each day which involve real risk?

There is perhaps no greater risk than to give oneself away through a lifelong commitment of fidelity in Holy Matrimony or a commitment to celibacy for the sake of the Kingdom of God. To love another person will always involve risk. To love God with all one’s heart and soul involves the risk of setting out into the unknown. However, what there is to be gained is too great not to take that risk. Whether it is to marriage and family life or to some form of service that will entail the forgoing of these goods, we need to form our sons to be capable of taking on the adventure of life, aware that there are risks, and aware that, with and through Christ, they are strong enough to take those risks. They will not be alone, for Christ has promised that He will be with us always.

Conclusion

We as a species are made for risk by and for one who took a “risk” in creating us. In giving us the freedom to respond in filial love to God, we are capable of gaining eternal life. We are also free to misuse our freedom and lose friendship with God. Without that risk initiated by God, our freedom which he gives to us in our creation and vocation as men and women, we would be incapable of a free response. We would be incapable of love. The very structure of our freedom means that—I would risk to say—God takes a risk that we may not respond with trust and with love to his gratuitous goodness in calling us out of nothing and into his marvelous light. The Orthodox theologian Vladimir Lossky writes about this in his book Orthodox Theology: An Introduction. While there are several excerpts which would suffice this one is the most succinct: “The person is the highest creation of God only because God gives it the possibility of love, therefore of refusal. God risks the eternal ruin of His highest creation, precisely that it may be the highest.”[34] Made in the image of God, who has taken the risk of creating us in and with freedom, we are made to take risks in turn, risks that will lead to more freedom, more joy, and more life. Deciding to take a certain action involves making decisions regarding what I know I am capable of doing and what I might be capable of doing. Crossing beyond the known to the unknown always involves risk. And yet, without crossing this boundary, there can be no growth and no progress. I will not be able to know what I am capable of if I do not take the risk of failing in my pursuit of something more than I have already done and mastered. This is true not only in the test of final perseverance. St. Paul reminds us that we have not yet obtained the prize of our salvation while we run the course of our earthly life. To listen to his words, it is clear that he was willing to take risks every day, confident that the Lord was with him. “[F]orgetting what lies behind and straining forward to what lies ahead, I press on toward the goal for the prize of the upward call of God in Christ Jesus” (Phil. 3:13b-14).

References

- William Arthur Ward, “To Risk” in Fountains of Faith: The Words of William Arthur Ward (Droke House: 1970).

- William Arthur Ward, Thoughts of a Christian Optimist (Droke House: 1968), 51.

- Jonathan Haidt, The Anxious Generation (New York: Penguin Press, 2024), 88.

- Helene Guldberg, Reclaiming Childhood: Freedom and Play in an Age of Fear (New York: Routledge, 2009). See also: Ellen Beate Hansen Sandseter, “A Norwegian Approach to Supporting Children’s Risky Play,” After Babel, 16 May 2025.

- Peter Gray, “The Decline of Play and the Rise of Psychopathology in Children and Adolescents,” American Journal of Play 3, no. 4 (Spring 2011), 458.

- Gray, “The Decline of Play,” 443.

- Julian Nowogrodzki, “Why Kids Need to Take More Risks: Science Reveals the Benefits of Wild, Free Play,” Nature 637, no. 266-268 (January 2025).

- Natasha Duell and Laurence Steinberg, “Differential correlates of positive and negative risk taking in adolescence,” Journal of Youth and Adolescence 49 (2020), 1162-1178.

- Quoted in Morgan Kelly, “Risky Play Exercises an Ancestral Need to Push Limits: Dartmouth anthropologists tout the benefits of monkey bars for child development,” Dartmouth, 6 September 2024.

- Cf. Christine R. Harris and Michael Jenkins. “Gender Differences in Risk Assessment: Why Do Women Take Fewer Risks than Men?” Judgment and Decision Making 1, no. 1 (2006): 48–63.

- Luke Fannon, Zaneta Thayer, and Nathaniel Dominy, “Commemorating the monkeybars, catalyst of debate at the intersection of human evolutionary biology and public health,” Evolution, Medicine, and Public Health 12, no. 1 (2024), 143-155. “Parents cite injury concerns for limiting thrill-seeking play on playgrounds, but such risk is low—calculated between 0.26 and 0.59 injuries per 100,000 uses—and dwarfed by organized sports or gym class as causes of hospitalizations.”

- Cf. Andrew Watson et al., “Soccer Injuries in Children and Adolescents,” Pediatrics 144, no. 5 (2019).

- Pamela Fuselli, “Keeping Kids Safe, Not Bubble-Wrapped,” Bringing Up Baby, 14 November 2022.

- Julian Nowogrodzki, “Why Kids Need to Take More Risks: Science Reveals the Benefits of Wild, Free Play,” Nature 637, no. 266-268 (January 2025).

- Pamela Fuselli, “I May Be Tired, But I Can’t Turn Away,” Parachute Blog, 7 July 2025.

- S. George Kipa, “Why Men Are at a Higher Risk for Unintentional Injury and Death,” MI Blue Daily, 28 June 2021.

- Cf. Kipa, “Why Men are at a Higher Risk.”

- Cf. Emilie Beaulieu and Suzanne Beno, “Healthy childhood development through outdoor risky play: Navigating the balance with injury prevention,” Paediatrics & Child Health 29, no. 4 (July 2024), 255-261; Christin Zwolski, Catherine Quatman-Yates, and Mark V. Paterno, “Resistance Training in Youth: Laying the Foundation for Injury Prevention and Physical Literacy,” Sports Health 9, no. 5 (2017), 436-443.

- Alvaro de Vicente, “Safety Is Not the Goal: Why Boys Need Risk to Flourish,” Profectus Magazine, 27 February 2025.

- “The Current Landscape of Adolescent Risk Behavior,” in Promoting Positive Adolescent Health Behaviors and Outcomes: Thriving in the 21st Century, ed. Robert Graham and Nicole Kahn (Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2019).

- The AA Charitable Trust, “Seatbelts Factsheet,” June 2023. Researchers in the UK found that from 2019 to 2023, the “overwhelming majority of young car drivers who die while not wearing their seatbelt are male (95%)” and that “young male car drivers are 4 times more likely than young female car drivers to die not wearing their seatbelt (34% young male drivers die unbelted in car crashes compared to 8% of young female drivers).” Also, “Male vs. Female Driving Statistics,” ConsumerAffairs Journal of Consumer Research, 25 July 2024. “Among the reasons that men are more likely than women to be involved in fatal crashes is their likelihood to engage in riskier driving practices, such as speeding and driving while under the influence of alcohol.”

- Quoted in Gemma Boothroyd, “The Risk Talk: Why Every Kid Needs One,” Alive, 12 August 2025.

- Nowogrodzki, “Why Kids Need to Take More Risks.”

- Ellen Beate Hansen Sandseter and Rasmus Kleppe, “Outdoor Risky Play,” Encyclopedia on Early Childhood Development, October 2024; Cf. Beaulieu and Beno, “Healthy childhood development through outdoor risky play.”

- Nowogrodzki, “Why Kids Need to Take More Risks.”

- Mariana Brussoni, “Why Children Need Risk, Fear, and Excitement in Play—And Why Adults’ Fears Put Them at Risk.” After Babel, 28 February 2024; Cf. Yousif Al-Baldawi, Maeghan E. James, Louise de Lannoy, and Mark S. Tremblay, “Injury statistics in outdoor compared to conventional early childhood education (ECE) programmes in Canada,” International Journal of Play 14, no. 2 (2025), 139-151.

- Cf. Doug Sundheim, “Do Women Take as Many Risks as Men?”, Harvard Business Review, 27 February 2013; Cf. “Understanding Risk-Seeking Behaviors In Boys And Men,” Better Help, 11 April 2025.

- Ellen Beate Hansen Sandseter, “Risky play? Adventurous play? Challenging play?” Ellen Beate Hansen Sandseter, 14 June 2016.

- Sandseter, “Risky play?”

- Ellen Beate Hansen Sandseter, Rasmus Kleppe, and Leif Edward Ottesen Kennair, “Risky play in children’s emotion regulation, social functioning, and physical health: an evolutionary approach,” International Journal of Play 12, no. 1 (2022), 127-139.

- Beaulieu and Beno, “Healthy childhood development through outdoor risky play.”

- Haidt, Anxious Generation, 9.

- Alvaro de Vicente, “Forming Wise, Courageous Risk-Takers,” HeightsCast, 11 December 2020.

- Vladimir Lossky, Orthodox Theology: An Introduction (Crestwood, New York: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1978), 73.

About the Author

Dr. Joseph Lanzilotti

Dr. Joseph Lanzilotti joined The Heights School faculty in 2022. He holds a Bachelor of Science degree in Biology with a second major in Philosophy from DeSales University, a Master of Arts degree in Theology from Ave Maria University, and a Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) degree in Theology from the Pontifical John Paul II Institute for Studies on Marriage and Family. Having grown up in rural New Jersey, Dr. Lanzilotti developed a great love for the natural world. He is a beekeeper and gardener. He enjoys trail running, swimming, and skiing. Joseph and his wife, Caeli, have a two-year-old son. They reside in Reston, VA.