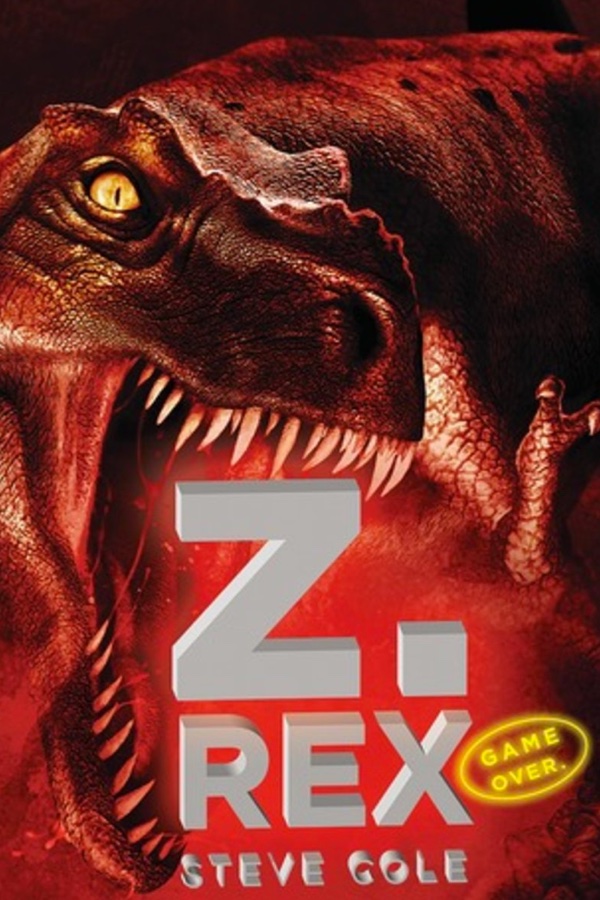

The Z trilogy, also known as The Hunting Trilogy, (Z. Rex, Z. Raptor, and Z. Apocalypse), by Steve Cole, is an unevenly written textual video game of a series, whose important defense of the dignity of the human person is almost drowned out by a combination of randomly inappropriate material and the bizarre ethical idea-soup it tries to pawn off on young adults.

The books are set in present day America and Europe, where thirteen-year-old Adam Adlar lives with his father, a genius scientist-programmer who can’t find a market for his Ultra Reality program. A creepy company called Geneflow Solutions hires him, and he’s soon forced to help them with a rather special project. (Hint: It’s making dinosaurs!) In the first book Adam and a certain scaly friend try to save Mr. Adlar from Geneflow’s clutches, encountering a fair amount of intrigue and mayhem along the way. Ultimately, the two Adlars must discover Geneflow’s ultimate plan, and put a stop to it.

Some juvenile readers will enjoy the dino-gore, as well as the hyper-evolved dinosaurs that also talk and fly and turn invisible and have special pockets inside their mouths for carrying stuff. And, oh yes, swim underwater. There are plenty of gross-out moments and explosions to tickle the fancy of the most screen-sophisticated youth.

On a serious note, the books do have a few very positive features. Atypically, there’s a father figure who is both present and is a relatively decent human being. A disabled character in the third novel forcefully defends her humanity against a genetic engineer who thinks she’s a biological mistake. The book attempts, unsuccessfully, as we’ll see, to defend the dignity of the human person against such horrors as human cloning and genetic tinkering with humans. In a flash of rare philosophical depth, a scientist (who is, with deliberate irony, an expert witness to the United Nations on medical ethics) announces to the protagonist that he “hates mysteries,” and the same man turns out to be one of the bad guys. Features like this would almost redeem the books as wholesome-though-mindless entertainment, if not for certain other weird shortcomings.

First, there is the by-now standard mismatch of prose and content. Like many young adult books, the prose is so simplistic that it seems aimed at eight- or nine-year-old readers, while the content is directed at a middle school or young adult audience. Also, the book has a great deal more melodrama than drama. Especially in the third book, there’s far too little meaningful plot movement, and far too much “zooming in” on characters’ emotional reactions, and on different angles of dinosaurs claws and such, to a minute and irritating level of detail. Even setting that aside, what is one to make of the author’s strange insertion of crude phrases at a rate of about two per book? For the most part, the books are innocent, if a bit stupid, except that we are suddenly jarred by a phrase like “by the short curlies,” or by the image of a female character “los[ing] her breakfast down her top.” It almost feels as if the editor demanded the author hit a minimum “rudeness quota,” since these moments don’t even fit with the tone or feel of the books.

The books also have a philosophy to pitch, and it’s a confused one. We’ll set aside the materialist nonsense that one can “evolve” an intellect and a free will. After all, talking dinosaurs are cool, and the author has to produce them somehow. At least he defends the reality of intellect and free will, and explicitly makes them the essential criteria of personhood. Yet at the end of the third book, after the villainess has given the standard spiel about why she did it, the protagonist’s father delivers this rousing defense of personhood:

You look at us like we’re walking, talking sacks of chemicals, but we’re not. [So far so good!] We’re people. [Yes!] We’re put here by chance, we’re shaped by happenstance, we blunder through life the best way we can. [Um…] It’s not the design that makes us better—it’s that journey.” [Wait…what?]

So in other words, kids, human life has special dignity because it’s not the product of any deliberate, meaningful plan, but, rather, because it’s a complete chemical accident. At least the author has done a good job of neatly summing up the absurd, self-refuting nonsense embraced by many contemporary “humanists.” A wise fourteen-year-old may indeed profit by reading this book. He would profit by seeing the need for something a great deal more robust than the meta-ethical narrative it offers.

In any event, the three books of The Hunting or Z series are a strange mix of innocence and crudity, of fun concepts and uneven prose, of promising themes and bad philosophy. The books are neither very bad nor very good. On the whole, there are more positive than negative elements, but readers should be aware of these deficiencies.

Discussion Questions:

- Josephs wants to improve the world by altering human genes, and by replacing people like Zoe. How would you argue against her position?

- According to this series, having a mind that can reason and freely choose is the mark of personhood. Could such a mind be purely material? Why or why not?