I am the blade that is swung by your hand,

“Threnody,” from the collected works of H.S. Socrates

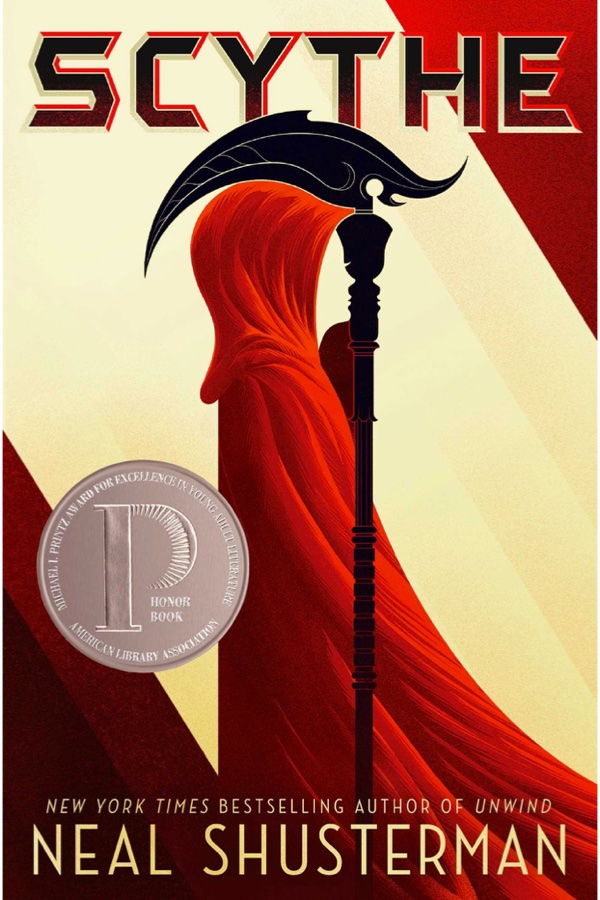

By the mortal-age shades of Donne, Dickinson, and Gray, this is none of your generic pop candy Y.A. fiction. Dignity and gravitas sound together to form the deep chords of this piece, and author Neal Shusterman is a somber organist. In Scythe , however, the bell tolls for no one at all, death stops by for only a chosen few, and churchyards in which elegies might be delivered are largely irrelevant. As are Donne, Dickinson, and Gray themselves. (They would be slightly dismayed, but probably not in the least surprised.) Scythe tells the story of Rowan and Citra, two everyday young people living in an interesting version of a plausible 22nd century… but no one really knows what year it is any more, because it stopped mattering. In 2042, all knowledge was taken up into an all-encompassing cloud called the Thunderhead. This thing is so much bigger than what we call “clouds” that the latter are not even mentioned. All combined human knowledge plus an active calculation of all possible consequences of any action resulted in the obliteration of such things as car accidents, disease, and famine. Simultaneously with the creation of the Thunderhead, humans figured out how to reset their physical selves to a younger age, resulting in virtual immortality. Ambu-drones automatically show up if anyone experiences fatality, take whomever is deadish to the nearest revival center, and a few days and couple bowls of ice cream later, they are good as new. Fatalities are usually intentional, since they are harmless and therefore funny, like Roadrunner and Wile E. Coyote cartoons. Enter the Scythes. As the name implies, they are a version of the grim reaper. But unlike the mortal-age version of that character, the Scythes are humans who are tasked with choosing those whose lives are to be ended permanently. (Death by fire is the only other permanent death.) The Scythes are not subject to the Thunderhead or any common social authority, and may choose whomever they will for any reason, or no reason at all. They are subject to a set of ten commandments, but are answerable only to an internal conclave. Their task is called “gleaning” rather than “killing.” Rowan and Citra are chosen to be apprentices to a Scythe named Faraday. This is not his real name, but the name of a mortal-age figure he has chosen to commemorate, given that all history, science, literature, art, you name it, is now redundant and reduced to a pastime for bored pedagogues and cranks. All Scythes choose their own such designation. The villains of the piece choose names like Goddard, Chomsky, Rand, and Volta. Sympathetic characters choose names like Faraday and Curie. The first Scythes (way back in 2042) chose names like Prometheus and Socrates. Our protagonists choose (or are given) equally interesting names, which I will not tell you. Make of these names what you will, but make something of them. Shusterman and his characters all picked them on purpose. Whatever their names, all Scythes are commanded to kill. It is a vocation, and many of them abide by vows very like the ecclesiastical poverty, chastity, and obedience. Also, one of the most serious requirements for wearing a Scythe’s robe is an extreme reluctance to do so. Moral dilemmas and personal conflicts ensue in intriguing fashion.

What I found fascinating about this book was its departures from common dystopian tropes. It might be described as a combination of The Book Thief , I, Robot and a truly benevolent 1984 , but as that description is wildly unenlightening, you should probably just read the book. Scythe is not, surprisingly, a story of an future dominated by Nazis, machines, or Big Brother. Also surprisingly, it is not about hot button issues such as population control or eugenics. Population control is rejected as the reason for the Scythes’ vocation. Eugenics only becomes an issue when a minority of the Scythes decide they are a superior class of beings. But these are the villains, who are distracting from the real issues, and who are outwitted and defeated in the fast-paced final act.

But none of the characters are two-dimensional to begin with, and even with the villains out of the picture, the biggest questions endure. The “good guys” struggle to understand even as they continue to act, and the “bad guys” have thought deeply before deciding… but there is a right and wrong in the world of this book, whether the characters have discovered it yet or not. The result, at least in the most relatable characters if not also in the reader, is a longing for the gift of discernment. Listing the ten commandments is easy. Living them is a much more precarious proposition. How do we discern between prudence and cowardice? Where is the line between zeal and bigotry? Between a sense of self-worth and an attitude of selfishness? These are a few of the questions which the book takes on.

The predominant theme is death, and how humans think and behave when faced with mortality. Queries about an afterlife appear, in spite of the fact that God has drifted out of most minds. After all, if we’ve made ourselves effectively immortal and we’ve created the omniscient all-caring being, what’s left to need? But something was lost in the process, and a longing for that persists through the story. Faraday suggests that longing itself, driven by the awareness of death, motivated humans to search, strive, and create. He teaches Rowan and Citra about art, science, literature, and philosophy, even though most assume these things have no meaning. Vague memories of the “miracles” that occurred during the “Month of Lights” (December) are bittersweet.

In the end, the protagonists struggle to discern the role of death in this artificially immortal society, because, as Scythe Curie puts it on the first page of the book, “Humanity is innocent; humanity is guilty, and both states are undeniably true.”

Here are the requisite parental advisories. There is no sex or profanity. Two references to gender and political issues are barely blips on the radar. The many portrayals of violence are sometimes gruesome but in my opinion non-gratuitous, as they are deeply and explicitly relevant to the themes of the book and directly illuminate character development. No moment of violence is taken lightly by the author or the characters.

Obviously I am a fan. I definitely would not want to wear that robe. And I find the name Caliban intriguing. Make of that what you will.

Discussion Questions

This book attaches a list of twenty discussion questions and eight extension activities. If you’d like something more, here are a few:

What role do the “tone cults” play in the book? Are they pursuing truth or falsehood? In what ways are individual Scythe names significant? How do they relate to the thoughts and behaviors of the characters? What do you think of Citra’s name choice, and of the name that legend gives to Rowan after he disappears?