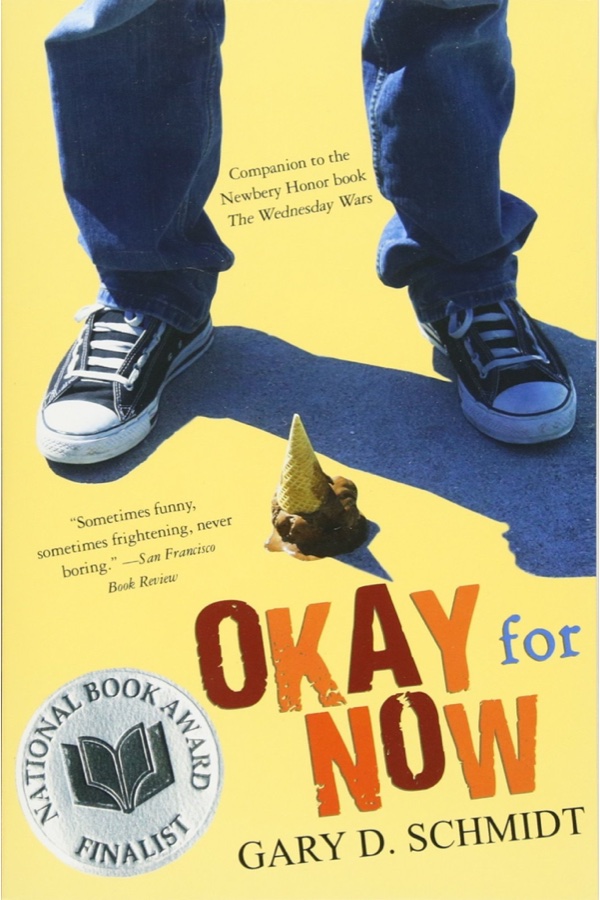

Okay for Now by Gary Schmidt is a familiar-feeling tale of personal growth set in the late 60s. Containing nothing overtly offensive, but composed almost entirely of elements you’ve seen or read before, the novel is likely to generate some very different reactions among its readers. Some will see it as a heart-warming redemption story, easily read, but not without a few nice literary touches, and a few surprising plot twists. Others, feeling that they have encountered the same story several hundred times already, and underwhelmed by its on-the-nose prose, may find themselves politely perplexed at its status as a National Book Award finalist.

As the story begins, things go from bad to worse for middle schooler Doug Swieteck when his troubled family moves from New York City to the small, upstate town of Marysville. Between his frustrated, factory worker father’s “quick hands”, and his violent older brother, Doug has learned to keep his soul well-insulated behind a mildly sarcastic exterior. He struggles to belong in a new community and in a new school, and he finds himself on the wrong side of several rather cruel adults. At the same time, chance encounters with goodness, beauty, and truth begin to effect in him a process of inner transformation that eventually spills out to improve the whole town.

The encounter with goodness comes through kind and perceptive adults who are able to see past Doug’s sarcastic front, and who guide him toward specific goals. Truth, to the extent that it’s an ideal in this novel, comes in the form of Doug’s acquisition of various practical skills that humanize him, and in his facing embarrassing facts about his life, without which personal and public honesty he cannot move toward healing. He encounters beauty in a girl name Lil Spicer to whom he eventually grows close, and also in a book of priceless bird paintings by John James Audubon.

The book of Audubon’s paintings plays a central thematic role. With each new painting, we learn something new about elements of composition, and about Doug. Not only do these paintings become the incidental cause for Doug’s development as a young artist, but they are oracles of his own life, external icons on which he projects his own problems. So when Doug, in a creative but subtle plan of redemption, begins recovering prints missing from the book, there’s a sense in which he’s restoring something missing both in himself and in the town. Marked shifts in the first-person internal monologue, and very metacognitive analyses of the significance of various bird paintings and other events, leave the reader in no uncertainty as to the thematic significance of this bird’s eye, or of that bird’s wing. And that’s the problem. As suggested earlier, Okay For Now is far too familiar as a story, and way too “on-the-nose” in its telling.

Examples of this are numerous, and listing them all might would come across as harping, or would give away some major plot points. Suffice to say that no symbol is left unexplained, no pearl unplumbed, no moment of serene quiet left un-intruded-upon. There is no moment to reflect, because the author is always telling us what to reflect on. Then there are the cliches: the father who drinks too much, the Vietnam trauma, the Mean Old Lady in the Mansion (Who – Surprise! — Really Isn’t Mean), miracle working teachers, etc. Near the end, the author even throws in a moment of very improbable and highly anachronistic political correctness that, sixties or no, would have been totally out of place in the year the story is set. It all felt very ready-made to me, as if Okay For Now were a literary product assembled by Doug’s father at the Ballard Paper Mill. Add to that a repetitive first-person voice that oscillates too obviously between “tender-but-tough city kid” and “reflective young artist”, and you have a novel capable of generating some very different reader responses.

Still, Gary Schmidt gives us a few things that are really unexpected, and rather nice. Very minor characters like Otis Bottom and James Russell stick out as real human beings, as does Officer Daugherty. Mr. Ballard, the successful businessman who owns the paper mill, is a good, thoughtful, and just man, whereas I expected Schmidt to portray him as a greedy shark. For the most part, I felt bludgeoned by the on-the-nose prose, and the constant repetition of the phrases, “Do you know how that feels?” and “And I’m not lying,”; however, the following passage sticks out as particularly poetic and moving:

You know, when someone has been crying, something

gets left in the air. It’s not something you can

see, or feel. Or draw. But it’s there. It’s like the

screech of the Black-Backed Gull, crying out into

the empty white space around him. You can’t hear it

when you look at the picture. But that doesn’t mean

it isn’t there.

I would have liked to see more of this, less chatty exposition, and more of an opportunity for the reader to react and reflect, but this seems to be the state of contemporary YA literature: everything must be obvious!

Recognizing real differences in readers’ expectations of and reactions to a YA novel, and recognizing the limitations in style that are, perhaps, imposed by the contemporary publishing industry itself, I can give the book a qualified recommendation for middle school readers. There is plenty of good in it, even if it’s not delivered in a manner that was to my personal taste. There’s some tough stuff in the the book, like physical and emotional abuse, and a reference to a famous war crime, but the book mostly steers clear of problematic content, and it also offers a redemptive story arc in which goodness, truth, and beauty finally defeat disorder, and in which several villainous characters receive opportunities to begin again. This National Book Award finalist is far from the kind of novel I’d prefer a middle schooler read, but, as a literary stepping stone, it’s okay — for now.