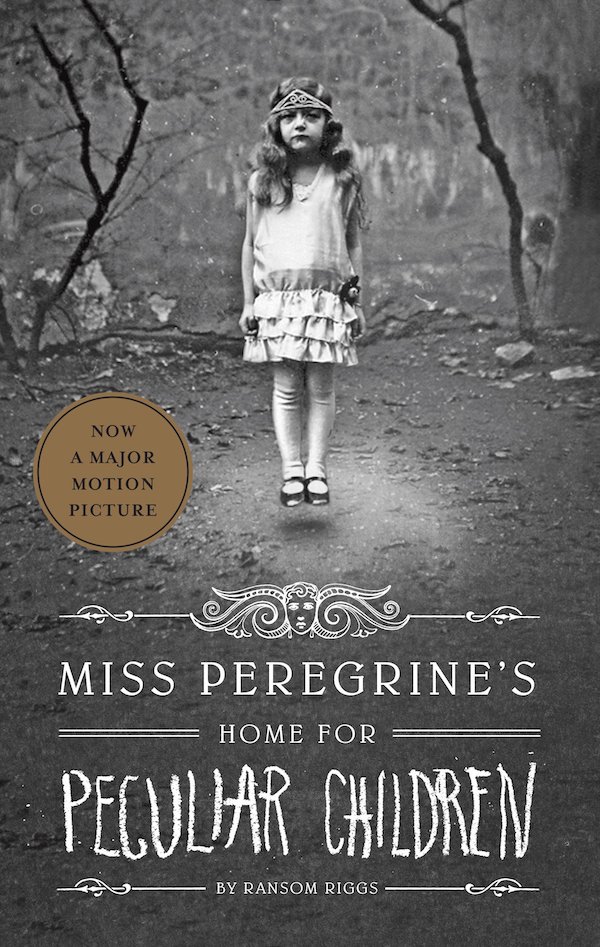

Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children is a story that grew out of old photographs. When author Ransom Riggs approached Quirk Books with his collection of found photos, many of them in sepia tones and featuring odd or surreal subject matter, the publisher suggested he develop a fictional narrative to explain the pictures. The resulting quirky novel was a New York Times bestseller, which has subsequently been translated to film. The book is absorbing, but is also marred by content that doesn’t seem right for its Young Adult audience.

Jacob Portman is an unhappy only-child, the fifteen-year-old heir to a drug store empire. When we first meet him, he’s doing the same hourly work as his future employees, work which he finds both boring and menial. We are supposed to sympathize with the protagonist, upon whom fate has unfairly bestowed a life of financial security, and who is consequently forced to go through the motions of “working” for the company that he will someday run. Jacob’s overprotective parents are similarly saddled with the need to fill their time with various projects. His father, being something of a kept man (since the family fortune comes through his wife, Jacob’s mother), is an amateur ornithologist who can never finish any of his birding manuscripts. Jacob’s one great love is his grandfather, Abraham Portman, who may be going senile

When he was a child, Jacob’s grandfather told him fantastic stories of a magical refuge to which he fled during the Nazi persecution of the Jews. These stories come with gray and sepia-toned photographs of what are supposed to be extraordinary children, children who float in the air, or who have super strength, and other peculiar abilities. But the photos seem like obvious fakes, and Jacob now doubts their provenance. Nevertheless, Jacob continues to revere his grandfather, a man who stockpiles guns, and who is increasingly certain that someone is trying to kill him. Responding to a frantic phone call, Jacob finds his grandfather bloodied and dying, and anxious to pass on a secret. When Jacob sees what killed his grandfather, he begins to doubt his own sanity. On the advice of his psychiatrist, Jacob, accompanied by his father, makes a pilgrimage to the fictional Welsh island of Cairnholm to do research on the strange refuge where his grandfather spent part of his childhood. Not long after arriving, Jacob begins to learn what’s actually going on.

The novel’s strong points include its convincing mix of history and fiction, its abiding sense of strangeness and mystery, and the believable foreignness of Cairnholm itself. There’s also relatively little political correctness in the places you’d most expect to find it. For example, guns play a legitimate role in self-defense, and alcohol and tobacco use are portrayed as normal in this context. Aside from the risible suggestion that a victim of pre-Christian human sacrifice probably wanted to be sacrificed, and a single line of victim-narration with Christians and Muslims as the baddies, there’s relatively little left-wing boilerplate. However, the book has other problems.

One is the pervasive abuse of God and Christ’s names. Another is the semi-frequent use of sexual vulgarisms. Both seem meant to lend a note of “realism” to the story, and yet they coarsen it. These things also contribute to a third problem, the novel’s atmosphere of spiritual grayness. Like the sepia-toned photographs that feature so heavily in the story, the imaginary atmosphere in which the story takes place also partakes of a certain metaphysical fatigue. It’s hard to put one’s finger on it precisely, but suffice it to say that the story has too much peculiarity and not enough wonder. Wonder requires humility, and innocence. A fairy-tale without those qualities can only offer intrigue and oddness, as is the case here. There is a sadness and a boredom to this world, not so much in the story itself – which is engaging enough – but in the metaphysical horizons it embraces. Sure, there are mysteries to uncover here, but then what? Frankly, after finishing the first book, I was too exhausted to want to find out.

This is not to deny the author’s skill, nor the cleverness of the story’s concept. It’s also quite possible that other readers will find the story delightful and full of wonder, not gray and world-weary, as I did. But even allowing for differences in taste, the harshness of some of the language leads me to question the publisher’s moral prudence. Who is this book’s intended audience? Some of the language used is objectively worse than the f-word, even if not so regarded by the book’s author. The mix of “young” themes and harsh language, along with a certain bleakness to the story, make me hesitate to recommend it to its intended Y.A. audience. On the other hand, one of the story’s plot reveals implicity affirms the dignity and inviolability of the marriage bond.

Judged as a whole, Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children is a mixed bag, an entertaining and cleverly-constructed novel that seems confused about its intended audience. Like so much contemporary entertainment, some of its content is too “young” for adults, yet too “old” for young adults. It’s too old in another sense; the weariness of its worldview reflects more the perspective of old, tired (and, perhaps, spoiled) men, than that of wonder-filled youth. While the latter judgment is hard to quantify, and may only reflect the reviewer’s personal tastes, prospective readers should at least be aware of the adult language sprinkled throughout it. Again, who is this fairy tale for? Read it with some caution.