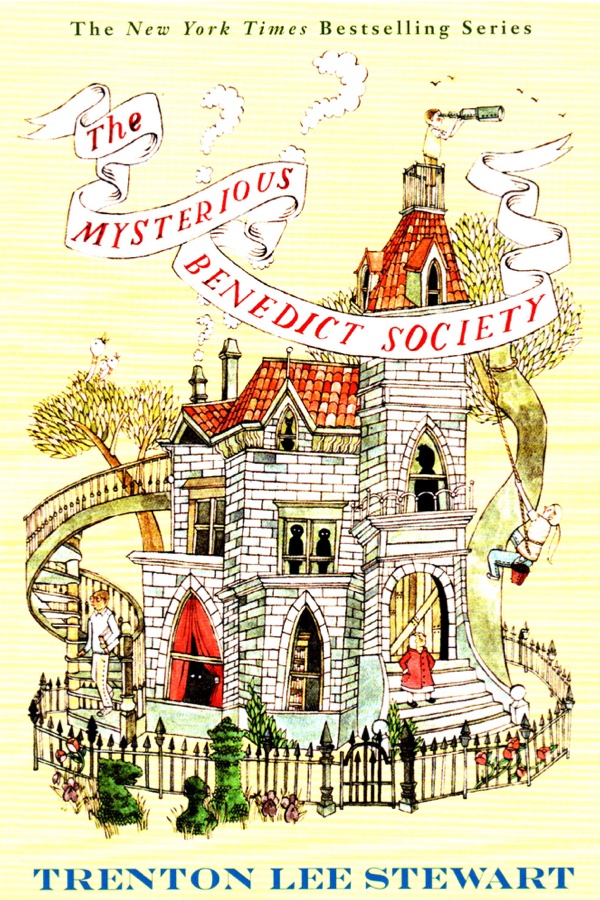

When I first saw Trenton Lee Stewart’s The Mysterious Benedict Society on a shelf in Barnes & Noble, my first thought was, “Great, another New York Times Best seller children’s series.” In general, great art—the possession for all time—seems to me to gain more approval as the generations pass, whereas the accolades for the piece that is designed for a favorable hearing start loud and dwindle with the attention spans that it has helped to erode. So I usually avoid bestsellers until they are a few decades old. It is summer, though, and the need to find a good recommendation for my fifth-grade son made a happy coincidence.

I will have to keep most of the story a secret, because I would not want to spoil the moment when Reynard Muldoon figured out how to pass the tests to get into the Society, how Kate Wetherby got Sticky Washington to reveal the mystery of his past in morse code, or the time when Constance Contraire received a very unexpected birthday cake. All I can say is that four children must go undercover to infiltrate The Institute and save the world.

MBS will evoke comparisons with Harry Potter. A team of two boys and two girls, selected for their unusual talents, try to thwart the plans of an evil genius bent on world domination. Stewart deserves credit, however, for putting these four heroes together in an original world without spells, wizards, or fantastical monsters.

It is often repeated that “every one…is essential to the success of the team” (119). Each of the four children is a primary example of one of the four temperaments—phlegmatic, sanguine, melancholic and choleric—and the dynamism of the Society as a team shows the beauty of their balance. The Society’s members are chosen because they 1.) are children and 2.) “love the truth” (101, passim). “Although most people care about the truth,” the children are told, “they can nonetheless—under certain circumstances, and given proper persuasion—be diverted from it. Some, however, possess an unusually powerful love of truth, and you children are among the few” (102). Their curiosity and simplicity are their strengths.

This makes them natural opponents to an enemy whose calling card is equivocation. The enemy claims that there are no rules—except that there are things you may not do. For example, “You can eat whatever and whenever you want, so long as it’s during meal hours in the cafeteria.… And you can go wherever you want…, so long as you keep to the paths and the yellow-tiled corridors” (171). Another one of the enemy’s lessons: “Because it was impossible, in the end, to protect yourself from anything—no matter how hard you tried—it was important to try as hard as you could to protect yourself from everything” (189). This lesson, about bacteria, is a microcosm for the oppressive idea of the Emergency (which looms over the whole story), which nobody seems to be able to define exactly, but about which all the protesters and the President agree “that something must be done, and soon” (97). Some heavy ideas for a young audience, but the story, which moves along with its own vitality, carries them easily.

MBS weaves together a fun plot with characters defined by moral choices, without tendentiously proffering right and wrong. When a character questions his own motives, or condemns those of others, he does it in character, with his own voice, not the author’s. For example, one of the heroes apostrophizes an absent friend: “Would you ever have thought I might choose a lie for the sake of my own happiness? [This] happiness is an illusion—it doesn’t take away your fears, it only lies to you about them, makes you temporarily believe you don’t have them.” The author’s voice does not obtrude when the orphan is tempted, by the promise of belonging to a group, to deceive himself. Even the dramatically necessary framing of a bad-guy character for a crime she did not commit leaves two of the heroes troubled by guilt (302). But how do they know that the authority that has commissioned them is to be obeyed against the authority of the Institute? Why do they trust Mr. Benedict? Do the members of the Mysterious Benedict Society need to place themselves outside the established structures of moral authority in order to accomplish their goals, like most child fiction heroes?

This is what makes the characters and the story as a whole so attractive. It pits those who accept the claims of the realities they encounter against those who declare that they can define reality. One character, upon giving his nickname to a bad-guy character, is asked if it’s his “real” name:

“It’s what everybody calls me,” Sticky replied.

“But is it official? Is there an official document somewhere that declares ‘Sticky’ to be your official name?”

“Um, no, but—”

“Well, if it isn’t official, then it can’t be real, now can it?”

Sticky just stared.

“Good boy, George,” said Jackson, leading them back toward the classrooms.

This is the central tension of the story. What happens when the beginning of cogitation is our assent to the reality that is in front of us—do we begin in wonder, and end in wisdom? And what happens when we claim to be able to master it—“Control is the key!” is a refrain that recurs throughout the story—ultimately, to define it for ourselves?

The Mysterious Benedict Society is a fun read, with an internal consistency of plot, and characters that demonstrate unity of personality. The author writes with a charm and a restraint that invites and challenges the reader to use his imagination and solve puzzles along with the heroes. Still, Stewart could have been more economical. The simple style of English for youngsters leads to a rather longer book than it had to be at 512 pages. He rewards the reader’s attention, even through the last chapter (you will be glad you stuck around for a last surprise or two after the action seems all over). I recommend it without reservation, and I am glad that my fifth-grade son enjoyed it enough to race through its two sequels before I could finish this first installment. Now that two of us are finished, my 6-year-old daughter and wife will have more time to read it.

Things to discuss…

- Think of the times when Reynie encounters Mr. Curtain. Why do you think he decides to remain loyal to Mr. Benedict?

- Do you ever feel sorry for any of the Executives? Which ones?

- How will the world be a worse place if Mr. Curtain succeeds?

- Who is a better hero, Reynie Muldoon or Milligan? What is something that each of them does that makes you like him less? How would the story have been different if they had not done those things?