I thought Daniel Nayeri’s Everything Sad Is Untrue was going to be one of those kinds of books. Parent reviewers complained of violence, and gave the impression that the author indulged in the kind of grittiness that mistakes mere excess for depth. To paraphrase several online comments, “I’m sorry all of that terrible stuff happened to the author, but is this really appropriate for children?” After finishing Nayeri’s nonlinear refugee memoir, I can’t help but wonder if we were all reading the same book.

Everything Sad is a good book. By that I mean that is fairly well-written – if you can get past the circuitous and chummy style – and that the content is substantive, and (mostly) edifying. There are a few problems, which I’ll address shortly. Yet as nearly as I can tell, what some readers really object to about this story is that it happened, and they would rather that it didn’t.

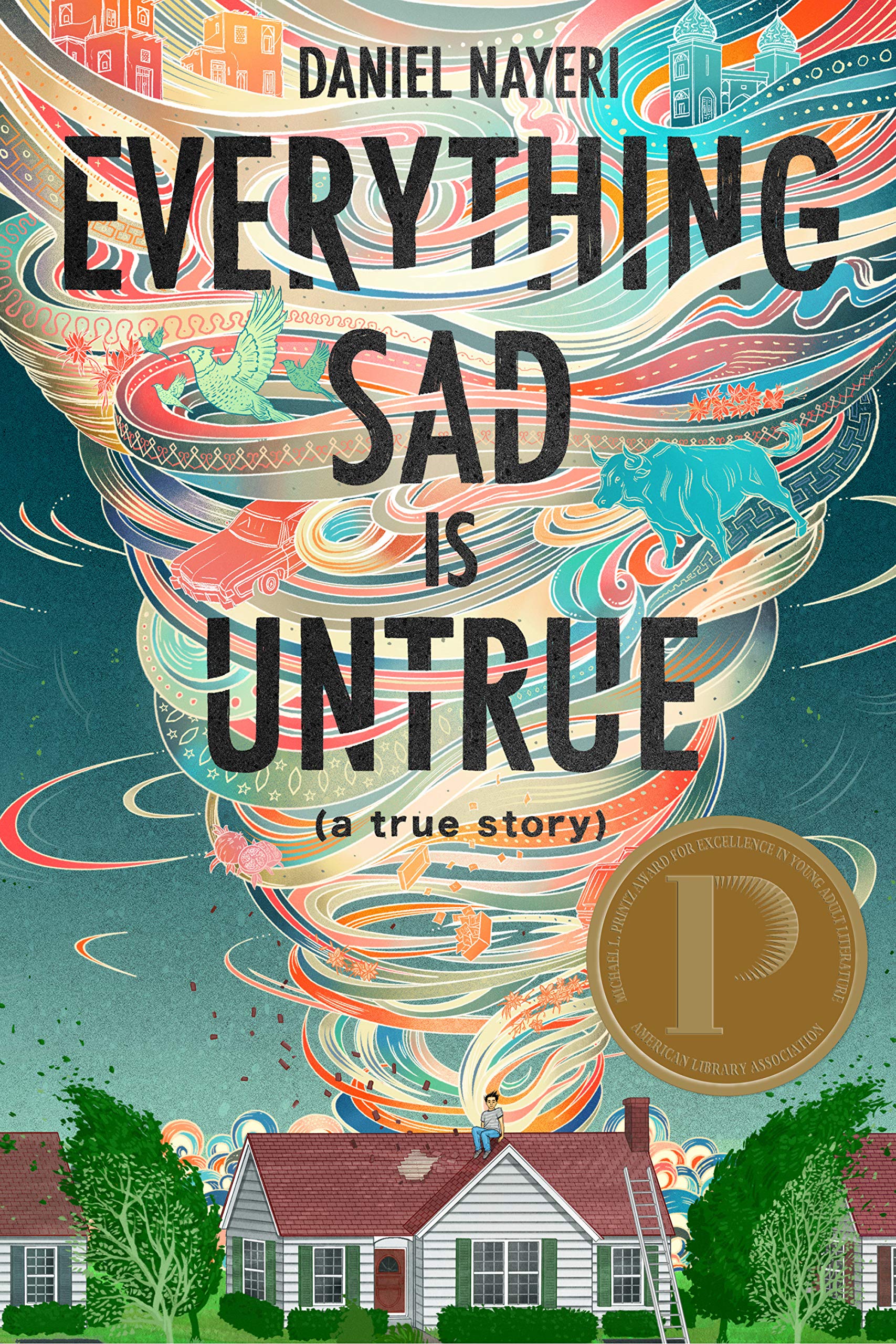

Moving back-and-forth in time, weaving from strands of lives present and ancestral that formed him, Daniel relates his family’s complicated journey from Iran to Oklahoma. Once upon a time, Daniel was called Khosrou, and he lived in Iran. His earliest memories were happy, though colored and embellished by hindsight. Indeed, the author stops frequently to reflect on the tricks that imagination plays on memory, including on one’s familial and cultural history. He does not balk at telling his own life story as if it were a myth, nor does he regard it as any less true because it is also chimerical. Taking One Thousand and One Nights’ Scheherazade as his model story-teller, Nayeri relates his personal experiences as strands in a complicated Persian rug. And Persian rugs, he frequently reminds us, have flaws.

The straightforward, linear account of his childhood goes as follows: Daniel lived in a beautiful house with his father, mother, and brilliant sister. His mother, a doctor, and his father, a loving scoundrel, provided well for their children, and had few troubles to speak of. Things went south for them when a series of strange, violent, and miraculous events led Daniel’s mother to convert to Christinianty. This fact was eventually discovered by the authorities. Since the penalty for conversion was torture followed by death, Daniel, his mother, and sister fled the country. After a painful period as refugees, the fractured family ended up in Oklahoma, where they contended with poverty, domestic abuse, and the general awkwardness of being culturally Persian in the United States.

Though written in the first person, the hero of Everything Sad is not Daniel, but his mother. With good reason, he compares her to Scheherazade, weaving order out of chaos, and to her savior Jesus Christ, taking violence upon herself to spare others. Though he keeps his own religious cards close to the vest, the author challenges his readers to explain the phenomena of his mother – not only her person, but the seeming miracles that led to her conversion and escape – in any way other than supernatural. It is not easy in contemporary America to produce writing that will appeal to conservatives and liberals, while making each uncomfortable. The former will not necessarily be pleased by the author’s portrayal of the plights of immigrants, nor at his mild jabs at American culture. The latter might not wish to consider Islam’s treatment of Christians, nor will left-leaning readers find it easy to deal with Daniel’s well-educated, “strong woman” mother – who happens to be a Bible-Christian. For finding a way to discuss these matters, the author should be commended. But there are a few elements to which readers may more reasonably object.

One is the aforementioned violence. In my opinion, this objection has no real merit, since the episodes mentioned are brief, told with great restraint, and – most importantly – actually happened. The author relates a few unpleasant moments, but he does not wallow in them. But he nearly wallows in something else.

As mentioned, Nayeri found a way to talk about very uncomfortable subjects without overtly offending political sensibilities. The way he pulls this off is by scattering his memoir with what he calls “poop stories.” These are uncomfortable episodes in his childhood when business did not go as planned. Though the phrase “poop stories” is jarring, and some of the tales are mortifying, there is a method to Nayeri’s madness. First, by making his readers uncomfortable in this way, he distracts them from the unproductive discomfort that comes with politics and stances. Like a comedian, he gets around his readers’ ideological defenses by making them cringe and laugh. Second, Nayeri uses these stories to highlight awkward points of difference between the diets of Easterners and Westerners, and between their respective norms of hygiene. I must admit, I learned some things; perhaps more than I wanted to know. In short, these elements will make you cringe, but they may be necessary evils. Just like…well, nevermind.

If a reader can make it through these things without holding his nose, he’ll find Everything Sad Is Untrue both moving and educational. As Roald Dahl did in his childhood memoir Boy, Nayeri takes painful, embarrassing, and sometimes violent moments, and reframes them. Nayeri’s ultimate theme is the self-consciously Tolkien-ish idea that dark things are only apparent, are passing away, and are therefore, fundamentally untrue. He sums up his philosophy in a quote from Dostoyevsky, with which I will also end this review:

“I believe like a child that suffering will be healed and made up for, that all the humiliating absurdity of human contradictions will vanish like a pitiful mirage, like the despicable fabrication of the impotent and infinitely small Euclidean mind of man; that in the world’s finale, at the moment of eternal harmony, something so precious will come to pass that it will suffice for all hearts, for the comforting of all resentments, for the atonement of all the crimes of humanity, for all the blood they’ve shed; that it will make it not only possible to forgive but to justify all that has happened.”

-Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Brothers Karamazov