The Artemis Fowl series has gained a wide readership for its mix of hilarious mayhem and snarky humor, but the series has some sketchy elements. Author Eoin Colfer regales his middle grade readers with that familiar, hyperactive style that reads in exactly the same way a Disney Channel teen actor acts. Imagine the bodiless and over-sweetened “energy drinks” that middle school boys seek out, throw in a heavy dose of sci-fi tech and explosions, add a half-cup of angry environmentalism and a few teaspoons of creepy cosmology. Then you’ll have a fairly accurate picture of this series.

C.S. Lewis once wrote that a story can have a normal protagonist in an odd situation, but not an odd protagonist in an odd situation. Colfer joins a long list of contemporary authors who gleefully violate this dictum by placing weird characters in weird situations. Authors who do this excuse themselves from the difficulty of creating real characters in a world with a believable feeling of depth. On the other hand, in such a bizarro world, the author is free to assert — or have his protagonists assert — anything he likes as true, so long as he can keep his readers engrossed by the spectacle of it all.

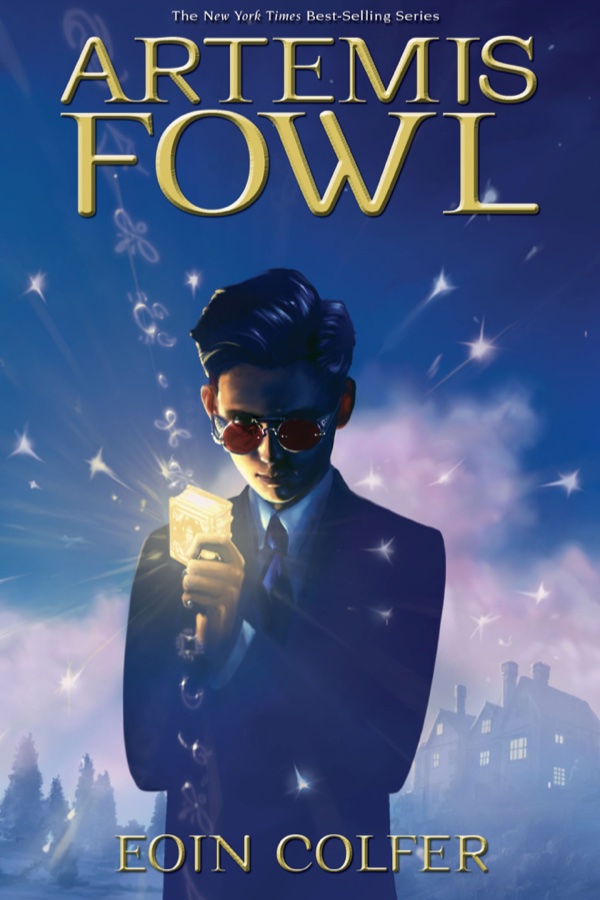

Artemis Fowl is an essentially unbelievable character, a twelve-year-old criminal mastermind who always outwits his adult opponents. The truest part of Artemis is that, like some real life twelve-year-olds, he harbors (unbeknownst even to himself) better sentiments beneath an anti-social veneer. His adventures begin when he kidnaps a fairy in order to hold her ransom for a large sum of gold. As the series progresses, Fowl finds himself in one high-stakes scenario after another, invariably triumphing in the end because of his superior mind. He’s joined in these adventures by Holly Short, the story’s stereotypical butt-kicking action girl, by several wiseacre backup characters who ‘tell it like it is,’ by a soil-excreting dwarf named Mulch Diggums, and by Fowl’s own perpetually loyal and physically imposing bodyguard, Butler. Eventually a maniacal sprite, Opal Kaboi, emerges as the series’ major villain, and her final defeat marks the series’ end.

The main strength of the books lies in their effective execution of an entertaining, if by now familiar concept: the collision of a character from the human world with characters from a parallel magical world. Many middle schoolers will find the books funny and engaging, and will enjoy their edginess. Eoin Colfer described the series as “Die Hard, with fairies,” and it’s true that this contemporary kids series with guns, explosions, and even a cigar-smoking good guy sometimes feels less packaged and politically correct than one would expect from a mainstream book. In marketing terms, the books are brilliant, but like Artemis’s supposed wit, the brilliance is mostly superficial.

As literature, the books feel pretty thin. Over time one begins to tire of the same kinds of quips, gestures, asides, and sarcastic elbow jabs. The plots are also surprisingly sparse, with relatively little actually happening in some books. Instead, what might be called “episodes of spectacle” fill in the gaps between major plot events. These episodes are generally snarky conversations that fill up space, intrusive comments from the narrator that fill up space, or descriptions of fairy novelties that either fill up space or provide an arbitrary, on-the-spot plot reveal, one which couldn’t have been foreseen or guessed because it’s really just “fairy ex machina.”

A similar criticism can be made of Artemis Fowl’s vaunted cleverness. For the most part, his whiz-bang solutions are unguessable only because their truth content is not obvious, or because they depend on information to which the reader has no access.True, Colfer generally drops in an early clue from which the perceptive reader might guess the surprise plot twist, but even so, Artemis’s reasoning process isn’t very satisfactory, and we are forced to take Colfer’s word that it all makes sense and that Artemis is simply wiser and more capable than those around him. This might seem a minor criticism, and it is, except that Artemis’s alleged intellectual superiority is his primary virtue. This fact indirectly points to what is ultimately wrong with the series: its gnosticism, and its anti-humanism.

The Artemis Fowl series is unusually hostile to the human race. Good characters authoritatively pronounce the human race a disease. Humans, or Mud Men, are criticized for having too many children, and our human fecundity is offered as the only reason for the otherwise impossible-to-explain ascendancy of man over the superior fairies. Humans understand essentially nothing, and are a “plague,” “bloodthirsty,” and so on. Meanwhile, the People (fairies) are enlightened, peaceful, and so on. To put it in contemporary political terms, fairies are woke. Besides being earth-destroying over-breeders, humans also mischaracterize spiritual and magical realities. For example, in the sixth book, the Kraken is not a ferocious, tentacled monster, but a peaceful giant — a sort of enormous whale — threatened by human pollution. Demons are also not evil, just a little rough around the edges. They are hostile to the human race because, well, who wouldn’t be? We’re such ignorant savages! N°1, a demon warlock, is a particularly enlightened and fun-loving guy, who even manages to like humans. He plays a major role in several of the final books and, although it’s never explicitly stated this way, he comes across as the best example in the series of how humans misconstrue even those spiritual realities they know.

To this reviewer, it was rather disconcerting to have a “good demon” appear in four of the novels. Given that a demon is supposed to be an embodiment of pure malice, a being that gleefully inflicts torture and cruelty and who deals in lies, one wonders what Colfer’s purpose could possibly be in rechristening, if one may so put it, this evil entity as just a fun rascal. A secular reader with no definite spiritual beliefs and who regards demons as mere symbols of evil might nevertheless ask himself if this is such a good idea. Despite the light tone, parts of the books seem unhealthily attached to spiritualism, occultism, and other forms of hokey irrationalism.

This seems to go hand in hand with a particular form of environmentalism which not only wants to save the earth from ravages of greed and from materialist reductionist mindset — a very good and commendable thing! — but which goes to the extreme of almost entirely dismissing the human race as a plague upon a semi-divinized earth. Though fairies are shown choosing to rescue humans from various disasters, the general message seems to be that we humans aren’t really worth all that much. The final book, The Last Guardian, does walk this pessimism back a bit, making Kaboi the enemy of fairies and men. It even states somewhere that “all souls are made for heaven,” which includes human souls. Still the books deliver a very heavy-handed dose of eco-ideology.

Yet, to paraphrase author Neil Gaiman, a child does not take from a book exactly what an adult would take from the same book. The middle school student who loves Artemis Fowl because of its action and humor may not even see the problems indicated above, or may set them aside easily for the sake of the parts that appeal to him. Moreover, at least one adult colleague (who read Fowl as a child and now lives without permanent damage) remembers only that the books were fun and exciting. He offered the view that story itself is a powerful medium, and added that because the notion of a magical world excites the imagination and creates and appetite for wonder, there can still be value in a series such as this, despite its problems. This reviewer cautiously agrees in principle, but with the caveat that it’s hard to know in advance which readers will be “immune” to Fowl’s problematic content and which are likely to be confused by it. This reviewer’s personal judgment is that the series can be acceptable for some readers, but really merits some parental discussion.

Discussion Questions

- In The Last Guardian, Artemis lies to Holly Short for a good cause. Is it permissible to tell a lie for a good reason? Can you imagine a way Artemis could have achieved his good end without lying?

- One group Artemis battles is the Extinctionists. Do you think there are really groups on earth that are elaborately planning ways to drive animals to extinction? If so, what are some examples of such groups? If not, what do you think is the author’s purpose in inventing such a group?

- Why do you think Colfer made demons essentially good, or at least morally neutral creatures?

- In the first book, holy water has power — it burns a fairy — but the antidote to holy water is another kind of fairy magic. What might Colfer be saying about the relationship between Christianity and folk magic/paganism?