How do you prepare to read (and teach) such an imposing and brilliant work of literature as John Milton’s Paradise Lost? The epic poem in blank verse landed like a conquering army on the plains of English letters, sprung from the windy peaks of Mount Parnassus, where the muses of poetry dwell beyond the heights of ordinary mortals. One doesn’t pick up Paradise Lost for a beach read or something to distract you on a lazy Sunday afternoon. That would be like listening to Wagner’s The Ring of the Nibelung while mowing the lawn.

The short answer to the above question is this: find a school like The Heights. I don’t mean this as a piece of self-promotion but simply as unavoidable fact: to become a member of the audience for whom Milton wrote, you have to have read a good portion of what he read in preparation for encountering his almost unmatched poetic oeuvre.

A young reader approaching Milton (1608-1674) for the first time should at least have a solid familiarity with the following titles or subjects: Hesiod’s Theogony, The Odyssey, The Iliad, The Aeneid, Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Arthurian legend, Spenser’s Faire Queene, plus a good handle on sacred scripture, as well as the development of the major Christian doctrines. Though this is only a part of Milton’s vast reading which he incorporated into Paradise Lost, and though this list alone can tax not only students but teachers (yours truly, of course), a student diligently working through the Heights’ curriculum will over the years find himself a part of Milton’s intended audience. Perhaps not in the front row seats, but there nonetheless. In a sense, it’s a permanent ideal, a reading plan for life.

It’s also what studying such works over the course of one’s time at our school can make a reality. That’s not to say my class on Milton this fall is for every student, or that every student in the class will automatically be enamored of Milton’s poetry. Nothing is education is automatic. That’s why in teaching there must be appeals to a student’s freedom, perhaps the ideal behind all the other ideals of teaching anybody anything.

Why do I like Paradise Lost so much? Aside from the fact that “like” is too weak a word for what I think about Milton’s work, the fascinating thing to me is how Milton turned his knowledge of so many songs, so to speak, into his own majestic music. One brief dip into Paradise Lost is enough to experience the power of his unique utterance. It speaks of an artistic assimilation on a tremendous scale.

Milton’s convictions, theological, political, or moral, might not be our own. In regards to scripture, he’s almost a school of scriptural interpretation all to himself, much of it dissonant to a Catholic vision of revelation. (His published tracts in favor of divorce for incompatibility earned him a reputation as a radical.) But the validity of his artistic achievement, I would argue, stands on its own merits. Beauty, after all, isn’t so much a conceptual construal of the world as it is a celebration, a liturgy of praise. Beauty shows within the work of art itself a glowing harmony that hints of a wholeness beyond this world, a paean that pulls us towards eternity even as it illuminates the fallenness from which it sprung.

Milton’s Life and Times

Great works of literature are sometimes compared to cathedrals: Dante’s Divine Comedy and Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales are two examples of this. Their structure is vast, intricate, interlacing, with textual light and shadow shimmering throughout their pages, often by a masterful control of tone and voice. Paradise Lost similarly vaults into the reader’s mind, adorned with thousands of lyrically perfect lines, bristling with contrapuntal scenes, characters, and themes. The epic voice at times seems less the work of one man than the voice of a literary tradition exceeding itself and losing none of its complicated sources whose allusions soar like verbal flying buttresses, roofing in its frame the world above—and in Milton’s case—the world below.

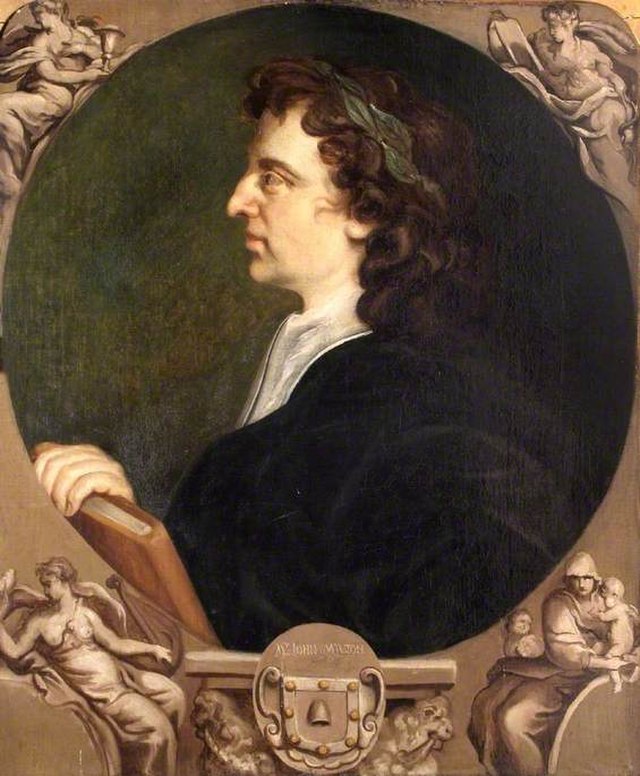

If ever a person dedicated himself to such a vast project worthily, Milton was that man. He was born in London, the son of John Milton, a scrivener (something akin to a notary and a law clerk combined), as well as an amateur composer and musician. We know next to nothing, unfortunately, about his mother. Milton’s upbringing was marked by tutors, intense private study, schooling at St. Paul’s, and finally, several years at Christ’s College, Cambridge, where he finished his Master’s Degree with distinction. He apparently did not enjoy his years at Cambridge. Some biographers attribute this to his unique devotion to scholarship, while others note the rising tide of religious uniformity at the university (and elsewhere) incompatible with Milton’s nonconformist views.

Milton seemed to be headed for a life of ministry in a nonconforming sect, but his disillusionment with clergy removed that as a viable option. He would, starting in the 1640s, get behind the political movement which led to the execution of Charles I in 1649. Milton, with two other poets as aides, John Dryden and Andrew Marvell, became Secretary of Foreign Tongues for the new Puritan Commonwealth. (Can you name another government office staffed by three great poets at the same time? I’m stumped.) After the death of Commonwealth leader Oliver Cromwell, and the restoration of Charles II on the throne in 1660, Milton, with two deceased wives behind him, would embark on his greatest poem amidst the ruins of his political ideals.

Ever-during Dark Surrounds Me

Yet he went on, despite the times, his personal hardships, or the challenges of writing an epic poem. Like the gorgeous greenery of Paradise, described by Milton as abundantly rich and ever-varied so that it seemed “wild above rule or art” because it spread its leaves entirely in sync with its Creator’s purpose, so too this epic unfurls with a maestro’s touch. Paradise Lost is wild and eminently civilized; exuberant and restrained; delicate and grand; earthly and cosmic; domestic and celestial; traditional and energetically innovative. Yet, for all that bardic virtuosity, there are a few times when the voice of John Milton, the man, comes through. Milton went completely blind in his early forties (pressure on his optic nerves seems the most likely cause). At the start of the third book after invoking the muse, which for Milton was the Holy Spirit, he reverts back to his own situation, his political hopes crushed, his voice steady:

Thus with the Year

3.40-50

Seasons return, but not to me returns

Day, or the sweet approach of Ev’n or Morn,

Or sight of vernal bloom, or Summers Rose,

Or flocks, or heards, or human face divine;

But cloud in stead, and ever-during dark

Surrounds me, from the chearful wayes of men

Cut off, and for the Book of knowledg fair

Presented with a Universal blanc

Of Nature’s works to mee expung’d and ras’d,

And wisdome at one entrance quite shut out.

Milton believed his muse nightly inspired him to compose his grand narrative. Two of his three daughters from his first marriage were often on call to take dictation of the rich load of verse he needed to unburden himself of in the early hours of the day. As many a biographer has noted, Milton said he felt like a cow that “needed to be milked” of his precious words that came in the double-darkness of night and affliction. His muse, whoever or whatever it was, certainly delivered. The “argument” of Paradise Lost is profound but straightforward. Milton tells us outright, he wants “to justify the ways of God to man.” How can God, infinitely good, create a world wracked by sin? Where, in such darkness, can we find light that endures?

Like all classical epics, we begin in the midst of the story: Satan and his rebellious angels have been tossed out of God’s presence, and fallen into the lake of fire in the depths of hell. Sounding very much like Homeric heroes, they orate high sounding speeches that rail against the Almighty. In Book II, we get the “plan” of God the Father to send his Son to redeem humanity which through Adam and Eve in Paradise will fall to Satan’s deceptive logic, bringing into the world “sin and all our woe.” Here we also get Satan’s plan to avenge himself on the Almighty. I can’t help seeing the following passage as a “hook” in the modern cinematic sense that pulls its audience into the action of the story. Says Satan, after much debate among his fallen crew:

There is a place

(If ancient and prophetic fame in Heaven

Err not)—another World, the happy seat

Of some new race, called Man, about this time

To be created like to us, though less

In power and excellence, but favored more

Of him who rules above; so was his will

Pronounced among the Gods, and by an oath

That shook Heaven’s whole circumference confirmed.

Thither let us bend all our thoughts, to learn

What creatures there inhabit, of what mould

Or substance, how endued, and what their power

And where their weakness: how attempted best,

By force or subtlety. Though Heaven be shut……this place may lie exposed,

2.345-361

The utmost border of his kingdom…

But “favour’d more / Of him who rules above…” We get much in this passage: Satan’s psychology of jealousy and spite, the odd idea of humanity’s creation being at a weaker outpost of God’s presence, an atmosphere of unimaginable epic distances, as well as a nod to Homer’s Zeus who often shook Olympus with his oaths. Satan’s speeches increasingly grow in eloquence allied with deception so much that a century or so later William Blake would say Milton was “of the devil’s party without knowing it.” Perhaps Milton knew something else: that eloquence disdains truth to its own destruction, whatever your political or religious allegiances.

Certainly, as Louis Martz makes clear in his Poet of Exile (1980), Milton, by the time he was writing his epic, realized what it meant to see a cause dear to him vanquished in battle. This gives his account of the rebel angels a certain sympathy, at least in his poetic rendering. As well, Martz shows how Milton’s language “defies grammar…alters the parts of speech at will…” This shifting language allows us to see several things going on at once in a few lines of verse, it is, says Martz, “a syntax of lightning.” And so, for instance, his description of Beelzebub also conjures images of Cromwell—whom Milton admired—as leader during much of the Interregnum:

Deep on his front engraven

2.302-309

Deliberation sat, and public care;

And princely counsel in his face yet shone,

Majestic, though in ruin. Sage he stood

With Atlantean shoulders, fit to bear

The weight of mightiest monarchies; his look

Drew audience and attention still as night

Or summer’s noontide air…

There’s no doubt, of course, that Milton thought that the rebels against God were on the side of the Royalists he despised, but such is the mystery of art.

***

Books V to VIII narrate Raphael’s message to Adam and Eve of their danger, as well as how war in heaven is at the root of their peril. Raphael also tells Adam about the beginning of the physical world, and we see the early chapters of Genesis spring to lyric life. Milton’s conception of creation here is a literal reading of scripture, quite at odds with the Church Fathers of late antiquity, but the effect is wonderfully poetic. As we’ll see, the reference to “pairs” throws a shadow of the Flood over the passage, hint of future fallenness:

Among the trees in pairs they rose, they walked:

The cattle in the fields and meadows green:

Those rare and solitary, these in flocks

Pasturing at once, and in broad herds upsprung.

The grassy clods now calved; now half appeared

The tawny lion, pawing to get free

His hinder parts, then springs as broke from bonds,

And rampant shakes his brinded mane…….the tiger, as the mole

7.459-470

Rising, the crumbled earth above them threw

In hillocks: The swift stag from underground

Bore up his branching head…

Book IX brings us the temptation scene (Milton here tells us his story must turn tragic) where Satan enters the serpent and finds Eve alone and boldly convinces her to eat of the fruit that was forbidden by God. Milton writes, “she plucked, she ate: / Earth felt the wound.” After her primal violation of God’s command, Eve almost instantly articulates a deistic version of God as an aloof, uncaring architect, “the great forbidder” due to his jealous promulgation of the moral law. Adam soon shares her plight, as do we all.

As Alan Jacobs has pointed out in his Paradise Lost: A Biography (2025), the dramatic tensions Milton works through the use of foreshadowing in the pre-fallen moments of Adam and Eve are what make this poem relevant to every age. Critic Joseph Addison put it well in the 18th century: who is unaffected by this catastrophe of our first parents? Much of our reading—aside from understanding the narrative—will center on this dramatic shadow which throws itself over the poem: the hints of “wanton” elements in Eve’s “ringleted” hair, as well as the strange dream she tells Adam about seeing her reflection in a stream and being taken by its beauty, mindful of Narcissus’ fatal infatuation. We can also hear this undertone in Adam’s rationalizations to himself to let Eve work alone in the garden—against his better judgment and Raphael’s explicit warnings. It’s no surprise critics have compared the poem to music, with its sweeping themes and paces of development leading to a complicated finale.

Encountering Milton

While critics of Milton have found him at times to have written a work almost too grand for the average reader (even Samuel Johnson said “none ever wished it longer”), Milton’s monumental achievement still stands unmatched. In the nineteenth-century, William Wordsworth would push the epic genre into later modernity with The Prelude (1850), but that work’s concentration on his own poetic journey—the poem is literally an autobiography—marks it in a distinctly different register than Milton’s. One, it’s true, rich in insight and eloquence, but also narrowed by a relatively constricting range of reference. Milton’s range is truly universal.

What will our students be doing this fall in my class? First of all, I hope they will be encountering Milton’s bardic voice, his inventive inclusion of so many other masters in his effort to make something new and yet traditional. Then, as we explore what he meant in thousands of poetic allusions and images, we’ll consider the great strands of stories that Milton weaves together from the ancient poets, from scripture, from the history of the political hopes and tragedies of his time. Along the way, we’ll also see how many of those stories, in their fundamentals at least, are our stories too.

Sources:

Barker, Arthur, E. Milton: Modern Essays in Criticism. 1965.

Hill, Christopher. Milton and the English Revolution. 1977.

Jacobs, Alan. Paradise Lost: A Biography. 2025.

Lewalski, K, Barbara. The Life of John Milton. 2003.

Martz, Louis L. Poet of Exile: A Study of Milton’s Poetry. 1980.

Milton, John. Paradise Lost, edited by David Scott Kastan. 2005.

Moshenska, Joe. Making Darkness Light: A Life of John Milton. 2021.

Tillyard, E. M. W. Studies in Milton. 1990.