In 1989, I was a recently married lieutenant in the Army, stationed in Germany, and found myself—to this day I can’t remember how—in possession of a book entitled A Retreat for Lay People. It was a series of talks by a priest named Ronald Knox that followed the general outline of a retreat. Till then, just about any spiritual reading I had done was reminiscent of the times, with lots of exclamation points and titles like In Search of Me. This man was different. His tone was conversational yet respectful. His assumptions were that you had a soul and you cared about it, that you had a brain and could use it. He was sympathetic but not indulgent. He had a sense of humor, but that was by-the-by, and the point was to get to the point. His prose, although I wouldn’t have been able to say so at the time, was, in a word, graceful. I liked him.

I’ve read much since by this man. Ronald Knox has become a sort of spiritual uncle, and the point of this article is to tell you a little about him. It’s not complete; I don’t have the space or intellect for that. Perhaps, though, it will convince you to read some of his work. He is a sound touchstone of not only how to think, but also how to act. That is a rare combination.

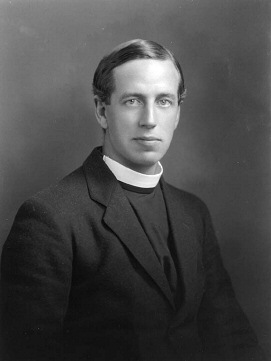

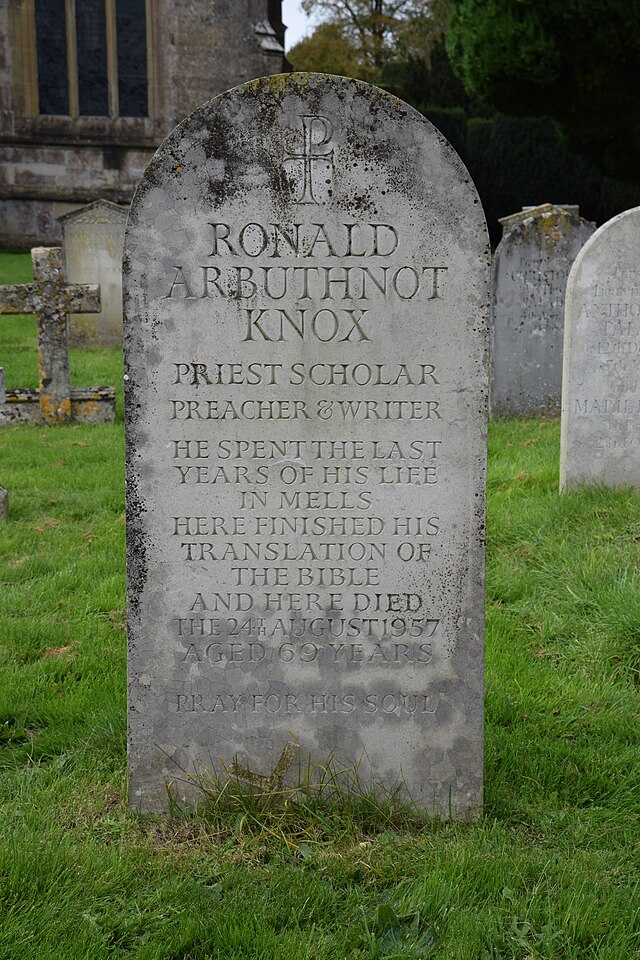

Monsignor Ronald Knox was born in Kibworth, England, in 1888. His father was an Anglican clergyman who would later become Bishop of Manchester. “Ronnie” (as his friends called him) was educated at Eton and Oxford and soaked in the classical tradition, winning prizes for Greek and Latin verse compositions. He had early felt a call to the ministry and was ordained an Anglican priest in 1910; in 1917, after much internal anguish (of which more later), he converted to Catholicism. He was ordained a Catholic priest in 1918 and, although shy and diffident, would be a major influence for the next forty years for just about the entire rich harvest of converts to the Roman Catholic Church in England during the twentieth century—especially among the literary class. Evelyn Waugh, G. K. Chesterton, Siegfried Sassoon, Christopher Dawson, Graham Greene, Edith Sitwell, Roy Campbell, Alec Guinness, Maurice Baring, and Arnold Lunn were just a few of these. He was even admired by those who didn’t come all the way over, but stayed in the “Anglo-Catholic” wing of the Church of England, such as Dorothy Sayers, C. S. Lewis, and T. S. Eliot, with Lewis calling him “possibly the wittiest man in Europe.”

His was what I would call an English spirituality: understated and reasonable, given to homely truths and allusions, having a love for nature and a preference for the small or local. A good example is his magnum opus, a history of heresies entitled Enthusiasm. It was not meant to be a compliment. Nothing so separates him from the modern mind, or endears him to me, as that outlook. He was personal and practical with a deep sympathy for human weakness.

Knox could converse with equal pleasantness and erudition on Transubstantiation, the works of Anthony Trollope, or the merits of the modern detective story. (He wrote several of his own and was one of the founding members of The Detection Club along with Agatha Christie, Dorothy Sayers, Baroness Emma Orczy, G. K. Chesterton, and others.) He was ideally suited to bring not only other Christians into the Catholic Church, but atheists and agnostics as well.

From Anglican to Catholic Priest

First, though, he would have to find—or more appropriately, be driven to—the Catholic Church.

In 1912, a group of leading Anglican theologians published a book entitled Foundations, which, by a method called “Higher Criticism,” questioned much of the supernatural in Sacred Scripture. In the search for the historical Jesus, they presented Him more akin to a great moral teacher than the Incarnate Son of God. This was just the latest in a series of “turf wars” that had been stirring in the Church of England between the “Anglo-Catholic” and the “Broad” (or “Evangelical” or “Liberal”) wings since the 1830s. Knox, seeing the danger, responded with practical intellect and humor. He used the principles of the Higher Criticism for an essay entitled “Studies in the Literature of Sherlock Holmes,” meant facetiously to show that the adventures of the great detective must have been written by several different authors. (He makes a convincing case.) More succinctly, he writes, “If I was to go to Heaven with the Higher Critics, it must be on the plea that invincible ignorance blinded me to the light of doubt.”

Ultimately, Higher Criticism raised the question of authority. Where did it rest in the Modernist era? Modernism is a difficult concept to pin down; Pope Pius X, in 1907, took a whole encyclical to do it. The basic idea is that authority rests with the individual, one’s own experience. Knox summarized it (and the crisis of Christianity in the twentieth century) in one of his best known epigrams:

When suave Politeness, temp’ring bigot Zeal

Corrected I believe, to One does feel.

For Knox at this time, as for most Anglicans, the authority was with the Church of England, which they saw as something of a concomitant branch of the Catholic Church. One has to appreciate the atmosphere of England in the early 1900s, the unbounded confidence when “the sun never set on the British Empire.” As Knox put it: “Only those of us, I think, who were born under Queen Victoria know what it feels like to assume, without questioning, that England is permanently top nation, that foreigners do not matter, and that if the worst comes to the worst, Lord Salisbury will send a gunboat.” As the debate about Higher Criticism showed, however, the Anglican Church was in a doubtful mood about its authority; in a way, it didn’t want to answer for it. Knox would later call England “the country of compromises.”

Being one of those men who push for answers, Knox looked for authority in the Nicene Creed where the signs of the Church were enumerated: one, holy, catholic, and apostolic. He saw that, for Protestant denominations, unity was something that once was and may be again someday. Meanwhile in the Catholic Church, it was something that once was, still is, and ever shall be. He reasoned: “If, therefore, schisms happen within the body of Christendom, the result of such schism is not to produce two Churches of Christ; what you have left is one true Church of Christ and one schismatic body; otherwise, after all these centuries, we should no longer be certain that our Lord’s promises held good.” As far as the term “holy,” Knox discerned an important distinction. Writing after his conversion, he described it this way: “Christians of any other denomination, if they describe that denomination as ‘holy’ at all (which they very seldom do), are referring in fact to the individual holiness of its members. Whereas when we talk about the Holy Catholic Church we aren’t thinking, precisely, of the holiness of its members. We think of the Church as sanctifying its members, rather than being sanctified by its members.”

The key to his own conversion, though, was apostolic succession, the faithful handing on of doctrine expressed in a continuity of ordained leadership. For Knox, this wasn’t just a question of authority; as a priest, it was a question of his vocation, his very life. He asked: “Matthew Parker had sent me; who sent Matthew Parker?” (Matthew Parker was the first Archbishop of Canterbury, appointed by Queen Elizabeth I.) Again: “That the Church of England possesses valid orders may, from the non-Catholic point of view, be arguable. That it possesses no commission handed down to it by direct succession from the apostles is a plain matter of history.”

As his country and the world suffered through World War I, Knox struggled with these questions. War pushed ultimate questions to the fore. Many of his dearest friends were at the front; several shared his questioning and, knowing they would die soon, had converted. Finally, on September 22, 1917, Knox doubted no more and was received into the Catholic Church.

Gracious Apologist

Following his conversion, Knox taught at St. Edmund’s College in Hertfordshire. Then, in 1926, he was appointed chaplain to the Catholic students at Oxford. He saw his mission as one not to inspire converts but to prepare Catholic students for life after the university. “The Church gets on by hook and by crook,” he said, “the hook of the fisherman fishing for converts and the crook of the shepherd looking after his flock, and I am more of a crook than a hook.” In what would be a divine twist of fate, though, it would be his books and collected sermons in apologetics that would lead many to convert to the Catholic Church.

One of Knox’s major public contributions to the Catholic cause during this time was with Arnold Lunn, an atheist, who had been so upset by the conversion of Knox, Chesterton, and others that he had written a book called Roman Converts, criticizing them and their beliefs. Surprisingly, he sent a copy to Knox, who even more surprisingly responded with a note: “Thank you for the compliment, for it is, I suppose, a compliment of sorts, like the crocodile pursuing Captain Hook.” Lunn was so taken aback by the graciousness of the response that he suggested he and Knox write a book in which Lunn would set forth his arguments and Knox would respond. This was a forceful but civil give and take between two high-powered minds, which makes for a compelling read. While Lunn’s arguments were forceful, what struck most readers was Knox’s reserve of strength and personal tone. As Lunn would write later, “Knox was addressing me and not a crowd of readers.” It did its job, for in 1933, Arnold Lunn was received into the Catholic Church by Monsignor Ronald Knox, which goes to show that good manners may be just as important in conversions as good arguments.

In his conferences and later apologetical works, Knox took pains to show that a Catholic didn’t believe the truths of the faith merely because “the Church said so,” but rather that the Church believed them because they were true—and it was precisely because the Church held on to the Truth that she drew others to her. Accommodating the world wouldn’t work: “Dogmas may fly out at the window, but congregations do not come in at the door,” he said. Like G. K. Chesterton and so many converts, Knox had a skeptical attitude toward modern civilization; he once called the toast rack the only really useful invention to have come along—and he saw the twentieth century as a “flight from reason.” With two world wars, a huge economic depression, the rise of the totalitarian state, and the deployment of the atomic bomb, he had good cause. Yet, it only strengthened his belief in the Catholic faith. “It is so stupid of modern civilisation to have given up believing in the devil,” he once wrote, “when he is the only explanation of it.” Knox also warned presciently about what would be the next great conflict: that of sacrificing the individual to secular notions of progress. “Our work is to colonize Heaven; theirs is to breed for Utopia.”

Preacher and Writer

Knox was not only an apologist but also a spiritual guide. The reflections he gave on retreats would become a series of books, e.g., A Retreat for Lay People, The Layman and His Conscience, and A Retreat for Priests (well worth reading for the layman, too). Then, as another example of unintended consequences, there was his “Slow Motion” series which came from talks he gave to a girls school that had moved into the house where Knox was staying during World War II: The Mass in Slow Motion, The Creed in Slow Motion, and The Gospel in Slow Motion. His tone throughout is casual but not patronizing. His gift was to illuminate theology’s very practical effects; he had a way of helping you see how a given virtue or point of morality affected you and what you should do about it. He never played on your emotions but got you to think about something till it worked its way into your heart. He did this, though, as a counselor and not an authority, as one who had thought about and worked through the issue himself. I’ll give some examples from The Layman and His Conscience.

On simplicity: “When you get down to it,” simplicity is “living for an end, and not allowing yourself to be distracted by side-issues.” Try to eliminate “undue attachment to a particular set of external objects and a particular way of living … not so much our possessions as our possessiveness … Don’t multiply, as far as you can help it, the number of things you can’t do without.” And, “learn to mind your own business … without peace of mind you can’t be integrated; your own life is impoverished when your whole attention is squandered on the lives of other people.”

On humility: “No, when all is said and done, it is a great part of humility to realize that there is nothing whatever to be humble about.”

On self-examination: “When man judges man, the accused knows whether he is innocent or guilty; it is for the judge to find out. When God judges man, the judge knows the truth already; it is the accused that has to learn it.”

Throughout his life, Knox’s one great love was the Eucharist. In one collection of his sermons, thirty-one are on this Sacrament—its ineffable mystery and humility. In one, he draws our attention to “the courtesy of Christ … always thoughtful and therefore always lovable.” Our Lord in the Eucharist is unobtrusive. “Even when we receive him in Communion, our faith must go out to meet him; he will give no sign to tell us who it is that comes to us, how it is that he comes to us. Easy to pass him by without reverence, easy to forget about him. He is just there if he is wanted; that is all.” Again, in a separate sermon, Knox writes that we must reach for communion through God’s “window in the wall,” mirroring the text from Song of Songs.

And at the window, behind the wall of partition that is a wall of partition no longer, stands the Beloved himself, calling us out into the open; … Come away from the blind pursuit of creatures, from all the plans your busy brain evolves … from the pettiness and the meanness of your everyday life … from the cares and solicitudes about the morrow … Come away into the wilderness of prayer, where my love will follow you and my hand hold you … Not that he calls us, yet, away from the body … [r]ather, as a beam of sunlight coming through the window lights up and makes visible the tiny motes of dust that fill the air, so those who live closest to him find, in the creatures round about them, a fresh charm and a fresh meaning, which the jaded palate of worldliness was too dull to detect.

To those who complain about the routine of the Mass, Knox had this to say: “Those who are not of our religion are puzzled sometimes, or even scandalized, by witnessing the ceremonies of the Mass; it is all, they say, so mechanical. But you see, it ought to be mechanical. They are watching, not a man, but a living tool; it turns this way and that, bends itself, straightens itself, gesticulates, all in obedience to preconceived order—Christ’s order, not ours … The Mass is best said—we Catholics know it—when it is said so that you do not notice how it is said; we do not expect eccentricities from a tool, the tool of Christ.” In typical English manner, he could offer the greatest compliment in an aside; this he did to the mother of Christ, Mary, in a homily on the friendship of Christ in the Eucharist and its influence: “But when we are speaking about the friendship of Jesus Christ, of course it is different. Nothing about us can influence him, there is nothing in him that needs to be influenced. If you come to think of it, I suppose he was the only person who ever came across our blessed Lady without being the better for it.”

In his later years, Knox worked on a translation of the Bible from the original Hebrew and Greek. When cancer overcame him in 1957, he was working on a translation of The Imitation of Christ by Thomas à Kempis.

So, that is some of Ronald Knox. There is so much more to him: his friendships with G. K. Chesterton (at whose funeral he preached), Hilaire Belloc, Evelyn Waugh, and others; his literary works outside religious matters; the care he took whenever he wrote or preached. I hope you will read him. You will find an apologist, a guide, a strong but gentle intellect, and a genial sense of humor. It may be that, as with most Brits, it takes you a while to warm to him; he wouldn’t mind that. As he might say, the point isn’t to get to know Ronald Knox; the point is to get to know Christ.

Recommended Short Reads (Online)

The Ten Commandments of Detective Fiction by Ronald Knox

Studies in the Literature of Sherlock Holmes by Ronald Knox

Recommended Books

A Retreat for Lay People by Ronald Knox

Difficulties: Being a Correspondence about the Catholic Religion by Arnold Lunn and Ronald Knox

The Layman and His Conscience by Ronald Knox

A Retreat for Priests by Ronald Knox

The Mass in Slow Motion by Ronald Knox

The Creed in Slow Motion by Ronald Knox

The Gospel in Slow Motion by Ronald Knox