Civilization is metaphor control. Now you may have noticed, that statement, literally, is a metaphor, and metaphors require civilized self-control to be wielded wisely. An uncivilized critic can always explode a metaphor, that is, expand it beyond its intended use in order to dismiss it, like so: “Obviously, civilization is so much more than poetic skill in the use of metaphors.” Thank you, my barbarian friend, but the first lesson of civilized metaphor control is accepting metaphors, as such. In order to understand whether the point of comparison between two things is true, we must respect the metaphor. Obviously, our barbaric hearts can abuse the metaphor, treat it as something it is not, such as a definition; that is, we can explode it and thereby render that most useful tool of human civilization utterly useless. If I had the power to add a definition to the dictionary it would be “Neanderthal: 7. (n.) an exploder of metaphors and civilizations.” I hope we are sufficiently civilized to recognize that “Neanderthal” is yet another metaphor. So let us walk a bit faster and leave behind the knuckle-dragging Neanderthals and facts-only barbarians of the lowlands, until we reach the high plains of patience, art, and friendship that lead up to the mountain palace of civilized metaphor, the very Heights of civilization.

But can you feel the barbarism in my use of so many wild and wheeling metaphors in the paragraph above? For as with everything, save charity and grace (but I repeat myself), there is always a golden mean. While the Neanderthal and barbarian cannot maintain civilization due to a lack of metaphorical thinking and control, the Epicurean, the Cretan, the aesthete (can you hear the punning metaphor?), the wild and romantic scribbler, the exaggerator, the liar, the gnostic, the subtle intriguer – all these are the enemies of civilization due not to a deficiency of metaphors but to an excess. Both the Neanderthal and Epicurean lack metaphor control, and such souls will not carry on – nor hand down – civilization.

What is civilization, then, you may ask. Many have tried to define it, and like a fool, I will court the same folly and give an answer the briefest of goes.

Daniel Webster, one of America’s most important statesmen wrote, “When tillage begins, other arts follow. The farmers therefore are the founders of human civilization.” The arts, in Webster’s reckoning, be they mechanical or humane, have everything to do with civilization. Now there is an argument to be made (and I’ve made it, long ago, in these pages) that the liberal arts or the arts of liberty are those high arts which aid us in the pursuit of virtue and the fulfillment of our loving duties to God and men. We might add, perhaps even metaphorically, that the highest of these arts is friendship. Civilization may have a great deal to do with the practice of the liberal arts, the arts of governance, law, and politics, and, in a fundamental way, the arts most closely associated with friendship. Etymologically speaking, “civilization” suggests as much: from the Latin civis, meaning citizen, the term concerns cities full of citizens, which are named for their relation, one to another, with mutual rights and obligations, held together as a people by, as St. Augustine so wisely put it, common loves. So it seems friendship and the arts that best assemble friends into sharing together a set of common loves are those arts most crucial to the maintenance and development of civilization.

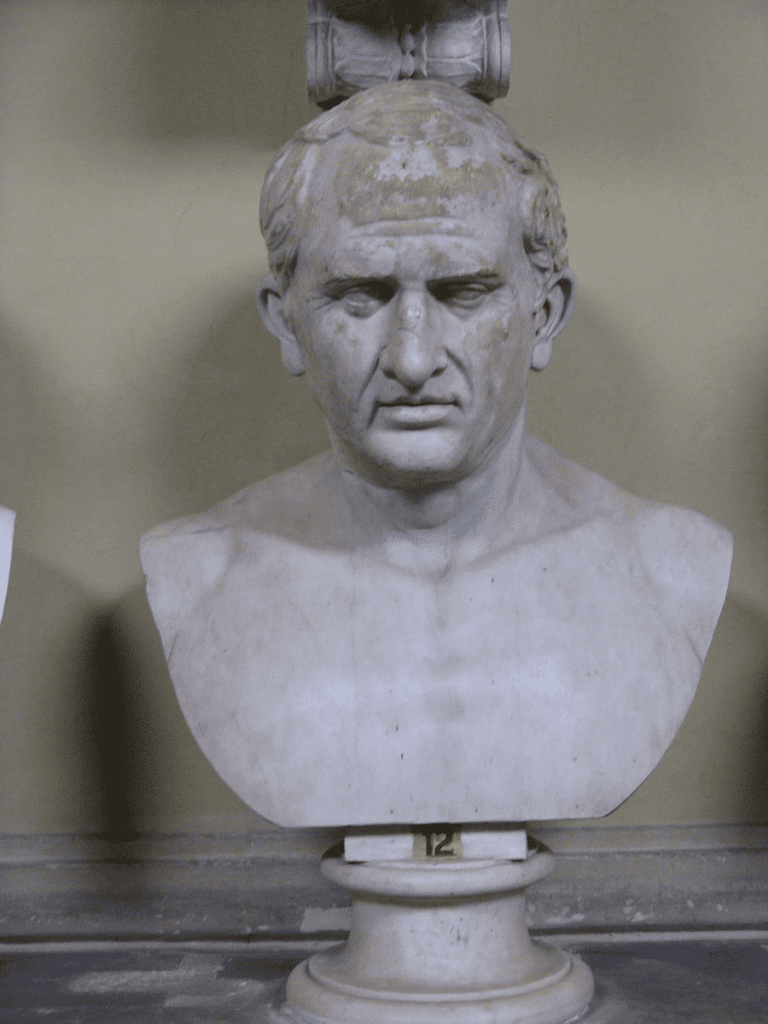

Well, we might press further, what arts best assemble friends into sharing common loves? And pressing still further we might ask, what arts most bring before the human mind and heart objects beautiful and lovable and, thus, objects sharable among citizens; given the complexity of any civilization worthy of its name, what arts can best aid our admiration and love of so many of our fellow citizens, present and past, and of their arts, habits, experiences, and sentiments; and what arts best allow us to share objects of affection that are so necessary and at the same time so manifold and, yes, so complex? To begin an answer to that battery of questions, we might look to one of our civilization’s most eloquent philosophers of both friendship and civic life: Marcus Tullius Cicero. “Tully,” as he was once called by our civilization (because we used to regard him as our very dear friend), referred to the republic, the political community, or, more simply, our city as our great complex of ordered loves. What arts magnify, strengthen, deepen, and sharpen a set of shared civilizational loves? Might it be that the lovable objects of virtue and truth, which we all wish our civilization to love, are most benefited by those arts most capable of complex and powerful beautification, namely poetry and oratory, the two liberal and humane arts that each, in their different ways, teach civilization its metaphor control? Obviously, these depend on other arts, such as history and politics, grammar and logic, because well-controlled metaphors must be comparing real and fitting things worth loving. But everyone knows the difference between the Gettysburg Address, a political speech made beautiful by the oratorical art, and a PowerPoint presentation on the same material. The one is lovely; the other, ugly. The former is civil and soaring; the latter is technical and inhuman.

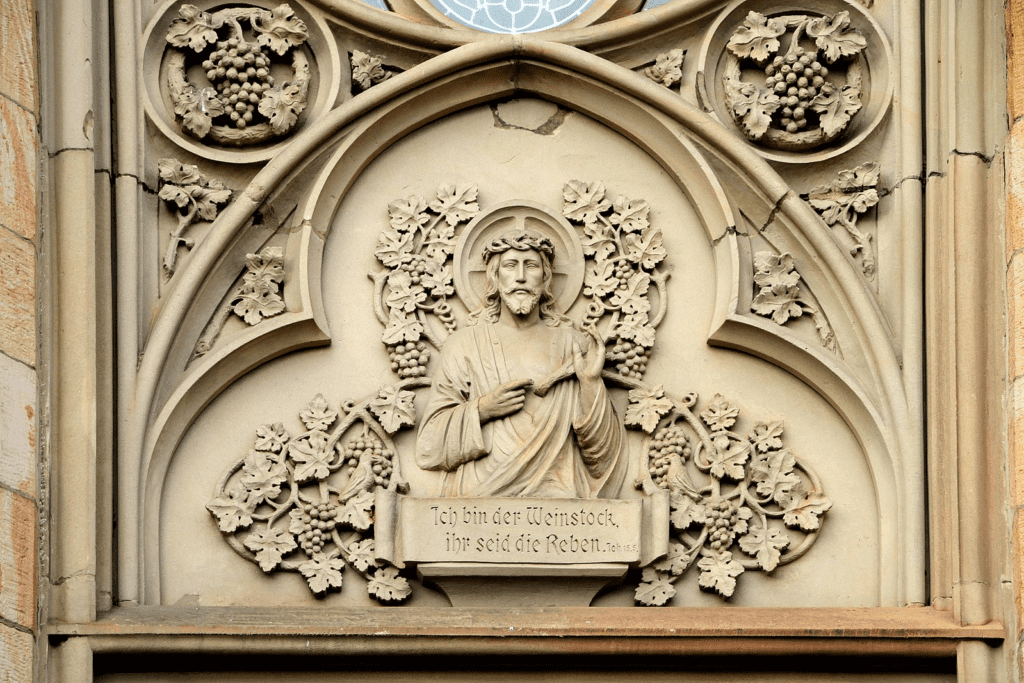

Recall that “civil,” “politic,” and “polite” are all words concerning affection and friendship. Friendships must be based in love and virtue, truth and trust, but even these are often not enough when they become wounded or even ruined by artless speech, ugly and harsh words, an inability to make oneself understood, known, and loved. The poetic and rhetorical arts, the arts of beautiful and persuasive speech directed toward truth – never a truth harsh or isolating, but always attractive and persuasive – are closely bound up with friendship, so much so that it is our civilization’s wise custom to regard friendship itself as an art, that most lovable art of friendship. Plutarch, the great and ancient moralist and historian, wrote that a bald truth told artlessly, at the wrong time, can do more damage and be more unjust than a lie. We practice friendship artlessly when we disregard the human heart’s penchant for gravitating toward beautiful truths and away from so-called ugly truths. That disregard becomes ridiculous if not outright unjust when we consider carefully such kind counselors as Shakespeare, Chaucer, Cicero, Newman, Hawthorne, Dante, Virgil, Horace, Plato, Seneca, More, Solomon, David, Isaiah, and of course, the greatest master of metaphor and parable, the Word Incarnate, Our Lord Jesus Christ.

But the truth must be spoken plainly, we may insist while clutching our stone knife. Yes, of course, at the right time, in the right way. Think how long the chosen people were slowly brought along by metaphorical prophecy before Christ, the Paschal Lamb, revealed himself. And when he did finally reveal himself, he did not forgo the use of metaphor even at the most intimate and revelatory Last Supper (“I am the true vine”), nor even on His Holy Cross; or do you think that Mary, our Mother, was not given to us by Christ in that most consoling metaphor: “Woman, behold your son”? So what then, we may stubbornly object, are we supposed to lie to one another until such time as we can speak the truth? And here again, I repeat, civilization is metaphor control. Not every truth needs to come forward at every moment; not every metaphor is a lie, especially if you can control them well. If God is Love and we are made in His image, then charity must be the rule of all truth, and friendship must be the rule that restrains even the pursuit of justice. Or as the famous grammarian H. W. Fowler put it, “Prefer geniality to grammar.”

This, our genial maxim that civilization is metaphor control, has particular importance in an era of confusion and chaos. When the storm churns the mighty waters and the ship of state or the Barque of Peter seems ready to founder or capsize, attention to metaphor control is an important way through the gale. And I’m sorry to say, I think even some of our very best have not wholly succeeded in friendly metaphor control and artfully maintaining the virtue most in need for a stormy time. The virtue I mean is the fore and aft anchors of Hope. The fore anchor, dropped from the bow, is well known to us. It is the clear and simple theological Hope in salvation, the Hope we each have in God’s aid to obtain the great and arduous good of eternal happiness with Him in heaven. But it is the smaller and oft forgotten stern anchor, at the back of a sailing ship, that I would like to remind us of now, for the simple reason that our minds and hearts very rightly concern ourselves with the more important fore anchor, and thus we can forget the aft anchor altogether.

So what is this subtler, smaller, aft anchor of Hope? It might be called optimism, except too many think too little of the term. Optimism means hoping for the best in an endeavor. And while many deride optimism as naïve, “dream and your dreams will fall short” is a pithy phrase to encapsulate a realistic tempering of more childish understandings of optimism. This aft anchor might be called natural hope, except natural hope is a kind of morally neutral passion that arises when any object of worth presents itself as an arduous good. No, there is something of virtue in the kind of hopefulness I’m speaking of here. Perhaps it is a certain aspect of prudence, not often written about by the ethicists but spoken of a great deal by the poets and historians. Or perhaps it is merely what our anchor metaphor implies, namely a minor aspect of the greater virtue of Hope.

Identifying clearly what it is that I’m describing may prove difficult because of a number of mistaken but persistent opinions and unwise metaphors that, while useful in their time, are outdated and overused in ways that hurt the fullest practice of the virtue of Hope as well as the virtue of magnanimity or greatness of soul. For example, how often have we heard some version of the following: “I don’t have to be optimistic; optimism isn’t a virtue. As a Christian, I have to be hopeful, and Hope only concerns reaching my final end, Heaven. Optimism about worldly goods is idolatrous. Hope in Heaven, but put not your trust in princes.” In one sense, this line of thinking is surely true. But in another, it may actually be a kind of cowardice or laziness or even small-souledness masquerading as piety and theological precision. Notice the metaphor? Optimism is idolatry. That’s an analogy, for clearly hoping for the best in a human endeavor is not the same as putting that endeavor above the worship of God. The argument above is in need of some metaphor control, for we can be optimistic or hopeful about a human project precisely because we hope in the Providential power of God, because we trust that God cares about our various human endeavors and wishes to, as the Psalmist prays, direct the work of our hands in this life toward success, in this life and the next. The insistence that God only wants to see us prosper in the next life mistakes the full power and Providential care by God of his children. We are commanded in the Gospel of Matthew to do good to those that hate us on the premise that it is an imitation of God, who gives His sunrise and rainfall to the just and unjust alike, in this life. To think that we should hope for no goods from our Father God in this life and expect only crosses and sorrows is to disregard the lesser anchor of Hope that we might attain arduous future goods on earth and not merely the great bow anchor of our final end in heaven.

Or take another metaphor from the twentieth century that we are perhaps overly fond of using, namely the reference to mankind’s life on earth as the “long defeat.” The proximate source of this phrase is nearly sacrosanct to many (myself included), but it is, I feel called to argue, a metaphor of perhaps darker initial provenance than it would first appear. The phrase comes from Galadriel’s elven lips in The Fellowship of the Ring: “[T]ogether through ages of the world we have fought the long defeat.” It is a metaphor for a long series of battles with the evil forces of Morgoth and Sauron in Middle Earth. But there are many victories in that metaphor of defeat, many earthly goods established, built up, and preserved. And all the while, what looked like defeat was a staging for the Age of Men, whereby many souls would live well and die into new life with the gods of Middle Earth, a thinly veiled literary analogue from Tolkien for man’s pilgrim life on earth unto eternal life. And that would be all well and good if the metaphor remained controlled in the story of the elves. Alas, civilization has not been so blessed. Tolkien himself reapplies his own elvish metaphor to the human condition in a now often quoted letter from 1956: “Actually, I am a Christian, and indeed a Roman Catholic, so that I do not expect ‘history’ to be anything but a ‘long defeat’ – though it contains (and in a legend may contain more clearly and movingly) some samples or glimpses of final victory.” While he tries to temper the less hopeful aspects of the metaphor by saying we catch “glimpses of final victory,” he describes life on earth as properly seen by Christians as a “long defeat.” But is that how we ought to see our time on earth? Yes, we may answer, “mourning and weeping in this valley of tears.” And yet, we are weeping in hope; as the Psalmist recounts, “[t]hey that sow in tears shall reap rejoicing.” Even the horrors of the Apocalypse, another perhaps unwise metaphor some use for our own time, is a victory of Christ, who will appear in order to rescue us at the end of a long battle of many victories for souls, through which every earthly power will be put beneath the feet of Christ. To emphasize the defeats instead of the victories seems bleak, like the pagan Norse myth of Ragnarök from which, I suspect, Tolkien plucked the feel and sense, if not the concept, of the “long defeat” in the first place.

Pope St. John Paul II spent a great deal of his pontificate in a sustained effort to help Christians adopt a more hopeful mode of proceeding in this world. In his now famous and, for our purposes, aptly named book, Crossing the Threshold of Hope, Pope St. John Paul II cautioned that our sense of a bitter and hopeless world comes from a residual “false image of God,” which came from an Enlightenment attitude toward God as “the Absolute that remains outside the world, indifferent to human suffering.” Instead, he admonished us to rejoice in “Emmanuel, God-with-us, a God who shares man’s lot and participates in his destiny.” Pope St. John Paul II preferred the overarching metaphor of a “new springtime of Christian life” that he saw as an important means to overcoming the twentieth century’s habitual despair, which was understandable given how many evils Christian civilization had to undergo in that time of fire and death. In his encyclical Redemptoris Missio, he was explicit on the point: “[I]n this ‘new springtime’ of Christianity there is an undeniable negative tendency, and the present document is meant to help overcome it.” Recall that the “Threshold of Hope” and “springtime of Christian life” are civilizational metaphors designed to counter such embittering Enlightenment metaphors as the “watchmaker god.” Clearly, the great pope understood that civilization requires metaphor control, especially as such metaphors affect the theological virtue of Hope and the natural passion of hope as well.

But we may ask, isn’t our saintly pope talking about heavenly Hope simply? Aren’t we mixing apples and oranges, so to speak? Isn’t Tolkien talking about the “long defeat” of human goods and John Paul II talking about the Hope of heaven? To answer, let me explain a question from the Summa, in brief, “Whether one man may hope for another’s eternal happiness.” The answer is, I hope you guessed, yes, on the grounds that, while Hope properly concerns one’s own salvation, if we presume the union of charity with others, then we may hope for another’s salvation as well. So it seems there is a kind of secondary hope for others that operates as a subordinate operation in the primary virtue of Hope – bow anchor and stern. But extend the argument: if we can Hope in God for our salvation and also for other people’s salvation, then we can hope that God will allow a certain number of human things in this life to prosper with sufficient order and peace, such that we may bring many more souls to Heaven with us. The pope’s encyclical Redemptoris Missio was, in English, titled “The Mission of the Redeemer,” and it discusses how we too are sent (missio) into the mission fields as fishers of men (holy mixed metaphors!). The implication that we see unfolding in this argument might be stated in the following formulation: if Hope trusts that God will help us to victory unto salvation, both ourselves and others, then we can hope in God to continue bringing about many good things in this life such that we have both the good soil and the good seed to continue the mission of Christ on earth. Thus we can and should drop the stern anchor as well and foster many earthly hopes, trusting that God will help us struggle to attain many arduous goods of civilization such that we might build up a great earthly peace to whatever degree God deems fit and for which we correspondingly strive. But we know – we have the hope – that God wants the spread of the faith and peace and justice in this life for that end. Thus, passionately loving the world and fostering great hopes for building up the human community are not opposed to heavenly Hope; rather these desires are a secondary anchor to steady us in the storm of life and in particularly turbulent times.

Much follows from these considerations. Magnanimity for the Christian is not limited to one’s own heroic pursuit of holiness and heaven; natural, social, political, and human goals – such pursuits of earthly greatness, in all humility, are worthy proximate goals of the great-souled. As such, a new responsibility can be seen and felt not merely to give ourselves and others an otherworldly exhortation to Hope in the next life, but also to speak in terms of lesser hopes for the betterment of society and the achievement of human goals on earth, such as peace, amity, concord, justice, education, a large and prosperous family, a business that is just, productive, and lucrative. This realization and habit forms bonds of friendship with those who do not share our otherworldly Hope but who do care about human society. And with these responsibilities of magnanimity and friendship comes a certain more careful governance of the tongue to preserve human goods of friendship, civic life, peace, order, law, common work, and family life. That is, we must be wiser in our metaphor control; we must feel responsible for earthly civilization in a way that ignorance of that less obvious stern anchor of Hope may cause us to forget or even scorn.

If the present ugliness of society has fostered still grimmer thoughts in us, we may still have a retort to all this, one I mentioned in passing above, namely the great exception, the unveiling, the end of the world. We may decide that these times look like the end times and so the normal responsibilities to foster human society are somehow relieved and we need only worry about preparing for the afterlife, like a dying man who rightly leaves off earthly cares in the last hours of his pilgrimage. But this is not metaphor control of the virtuous. I’m afraid this is a combination of intellectual pride and cowardice that we ought not to indulge.

A few brief anecdotes may help to explain. A dear Evangelical friend of mine once bested me with scripture on the literal level like so. He’d been predicting a theory of the end times, with embedded microchips as the sign of the beast; the then-Prince Charles of England was somehow involved. To try to calm his somewhat fevered speculations, I cited holy scripture: “Don’t forget, ‘you know not the day nor the hour.’” He took a long beat and then dryly and wryly responded, “Well, that may be, Matt, but you can sure as hell know the month and the year.” After a good, long laugh, I reflected that this literal interpretation was a lack of metaphorical control. Obviously, the point of Christ’s words here in the Gospel of Matthew was to warn us to remain vigilant, doing one’s duty and living in utmost charity at all times because the end will surely surprise us. Our Lord goes so far even to say that “Heaven and earth shall pass, but my words shall not pass. But of that day and hour no one knoweth, not the angels of heaven, but the Father alone.” More recently, a friend confided that he thought these were the end times. I shot back, perhaps too glibly, “Don’t be lazy. You only wish we didn’t actually have to clean up this mess.” What’s more, the work before us may call many to great sacrifices. And there are the inevitable crosses, some of them truly formidable, that accompany any Christian life. So, if we claim to see the impending Apocalypse, what not even the angels can see and that which, we are told by God, we cannot predict, then perhaps we are not acting as we ought. Perhaps we are not acting as earthly creatures with earthly work in our hopeful and humble hands. Perhaps instead, it is our human way to do our loving earthly duty, buying and selling, marrying and giving in marriage, unto the last moment. When we indulge in apocalyptic speculation, when we raise – or worse, cut loose – the stern anchor in this fevered way, I suppose we might also be fostering a foolish desire to avoid being tricked by God’s surprise crosses or His surprise end of the world, as if doing one’s hopeful duties to the end were not the best possible preparation for facing disasters or one’s final judgment. As I said, the claim to see more than we really can does look a bit like pride, and the desire to be relieved of labor and sacrifice to uphold and rebuild civilization looks a little like cowardice or at least sloth and laziness. There is work to be done and done in Hope.

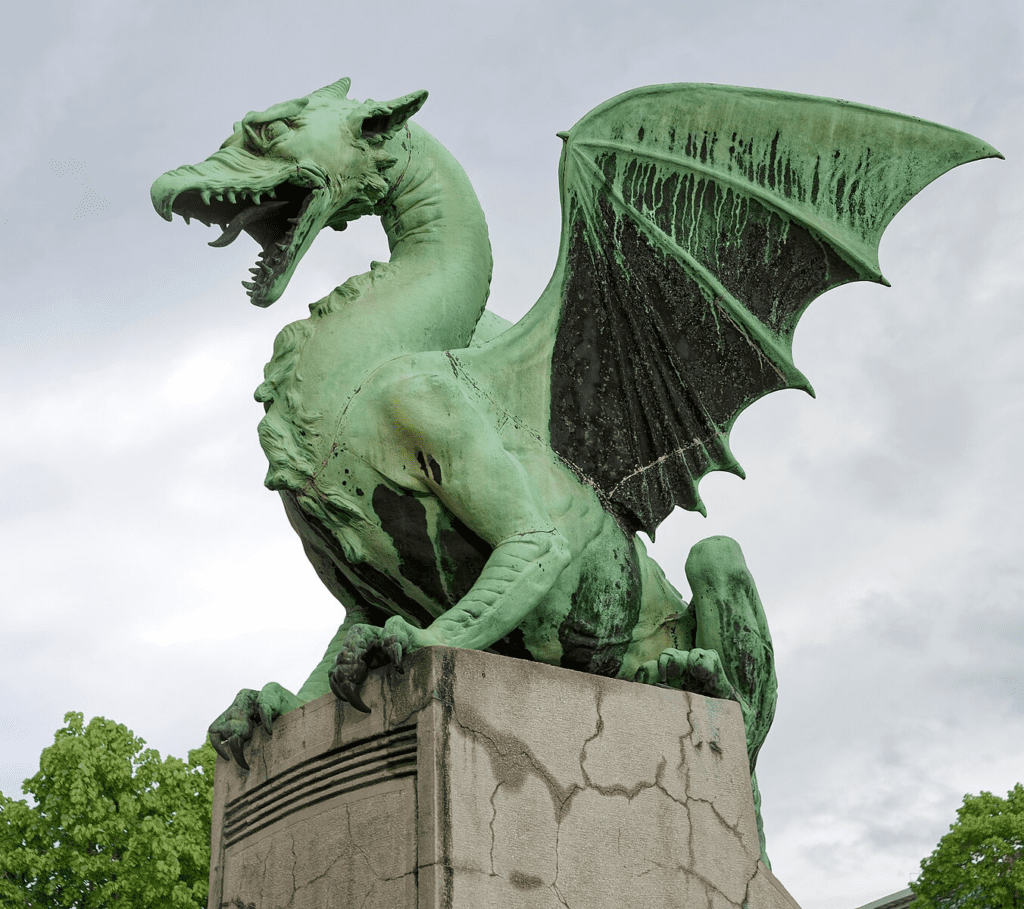

Metaphor control, it turns out, is required for reading the two great books, the Good Book of God’s Word and the Book of Life. And so I’ll repeat the maxim once more: civilization is metaphor control. Indeed, metaphor control may even be a lesser hope of mankind, metaphorically speaking. Let me close with a kind of grand metaphor, controlled in such a way as to foster these important lesser hopes. It may be wrong, but then it is only a metaphor. With metaphor control, we use them thoughtfully, nevertheless, to help us through life. When we look at the twenty-first century, with all its societal ills and political chaos, we can feel as though civilization is unraveling before our eyes. But what if we really are crossing a threshold of hope into a new era of Christian peace? What if the twentieth century introduced a great dragon of violence and error? Its head burst into human history with gnashing teeth and fiery breath with two world wars. Its hulking body then crushed the world with global communism and a long, Cold War. And now, our generation is left with the chaotic, thorny, and flailing dragon’s tail to subdue. The great dragon is in its death throes, and its tail may wipe out a good many in the fight. But there is no mind to these thrashing paroxysms of society. These are the necessary battles of a mop-up operation. For us Tolkien fans, it’s like the putting down of the last oliphaunts at Pelennor Fields. Still much danger, but this battle, at least, is coming to a close.

Now of course, we can explode these metaphors in a thousand ways. In fact, the dragon features in the Book of Revelation. But we must hold our hearts in Hope, my friends, and, as I’ve argued here, in hope.