When you take pen in hand and write a word, you do something approaching the divine. You are giving physical form to a thought. It is, in its way, an Incarnation. To do this with beauty and grace is to honor this Incarnation. This is penmanship.

Along with speaking, it is the most common form of Incarnation. We do it every day whether we’re signing a credit card receipt, writing a grocery list, or putting down our deepest thoughts in a journal. Like all Incarnations, it reflects who we are. And I think it sad, very sad, we think so little of it.

Gone are the days of graceful, legible letters sliding across a page; of pens and pencils making the mind and body partners in this divine act of the formation of a word. Now it is just punch, punch, punch, with about every fifth punch the wrong one so his comes out hit and fate comes out face, and you end up with hit face instead of his fate. Today, to propose penmanship as a serious scholastic subject is to be viewed with something close to suspicion. But we should esteem penmanship for two reasons: one, it does have a place in education and, two, it is an act of creativity and beauty.

We abandoned penmanship because of technology. Why waste time, so the thinking goes, learning how to form letters when we have word-processors (which makes writing sound like sausage making)? Besides, what adult actually writes anything of consequence anymore? We peck and poke on keyboards, or tap on (or speak to) “devices,” which will then correct (we hope) any mistakes we might have made in spelling or grammar. We say that because we have a technological way of doing things, a way that (supposedly) saves time and effort to get (supposedly) roughly the same results, we should jettison the old way. Our concern is efficiency.

Efficiency—economy of effort—is fine, but it is not education. Education, you see, is not only about the “what,” but equally, and perhaps more importantly, about the “how.” A more formal way of saying this is that education is not primarily about the distribution and acquisition of information, but more about the formation of habits of the mind. What is more, when we allow a lower good to replace a higher good, we lose both the higher and lower good. That is, when we view education as primarily the efficient acquisition of information—as opposed to formation of good habits of the mind—then, in the end, not only shall we not have good habits of the mind, but we won’t efficiently acquire information.

So what does this have to do with penmanship? Well, words are important. We use them to think, and so one of the “first things” of education should be the proper attitude towards words. Everything about a word—its meaning, sound, history, formation, pronunciation—should be approached with reverence and awe. I suspect, if I may be so bold, that God agrees. He has called Himself The Word. Also, consider our Lord’s words about, “heaven and earth must disappear sooner than one jot, one flourish should disappear from the law” (Matt. 5:18)? The words translated as “jot” and “flourish” refer to small parts of Aramaic letters. I don’t think our Lord was being entirely hyperbolic here. Remember the Jews were a people of “the Book”; it is one thing that greatly separated them from their pagan neighbors. The Hebrews’ faith and law were written down; in the case of the law it had been written in stone, by God. It wasn’t for them to be messing about with it.

Medieval monks understood this, too. They didn’t simply copy manuscripts, but colored and embellished them because what they were doing was worth the effort. Witness the glorious Book of Kells. By taking pains with the very letters of the word of God, they believed they were becoming one with The Word of God.

And so with penmanship: if we want our boys to value words, then we should want them to value words in every aspect, including how they are formed. Just as a meal is valued more by those who prepare it and those who eat it if it is “formed” better—home-cooked, served on a plate, with the steak here, the potatoes there, the veggies on the side, the napkin folded neatly, the wine in a wine glass—than if it is put together more “efficiently”—processed and in a plastic wrapper with a paper cup—so a word is more valued if more care is taken in its formation. And this is true again both for the writer and the recipient. We put more thought into a handwritten note than an email, and feel more valued when we receive the former than the latter.

That this takes time and effort should not surprise us. All good things take time and effort.

I am not averse to all uses of computers, but just as we insist that boys know their multiplication tables before we let them use calculators, we should require them to write legibly before they start using computers. Even after that, they should take notes by hand. It is a fact that those who write their notes in class retain more information than those who use keyboards. (Remember what I said about losing even second things when you put them before first things?)

Writing by hand also reinforces correct spelling and helps to unlock the meaning of words. If we have formed “i before e, except after c (or when sounding like a as in “neighbor” and “weigh”) enough times, the rule sinks in. When we write by hand we also sound out our words more, which makes us more attune to their meaning and nuance. We become sensitive to their rhythm and cadence, the effects of alliteration and assonance. This helps our composition. Furthermore, there is strong evidence that teaching penmanship helps children with learning challenges such as dyslexia and dysgraphia. Writing in cursive (as opposed to print) connects letters to each other, reinforcing the connection between the letters, the sounds, and the words. It stimulates the brain in ways that printing or typing on a computer does not. This may have some relation with penmanship’s attribute of beauty—but more on that in a moment.

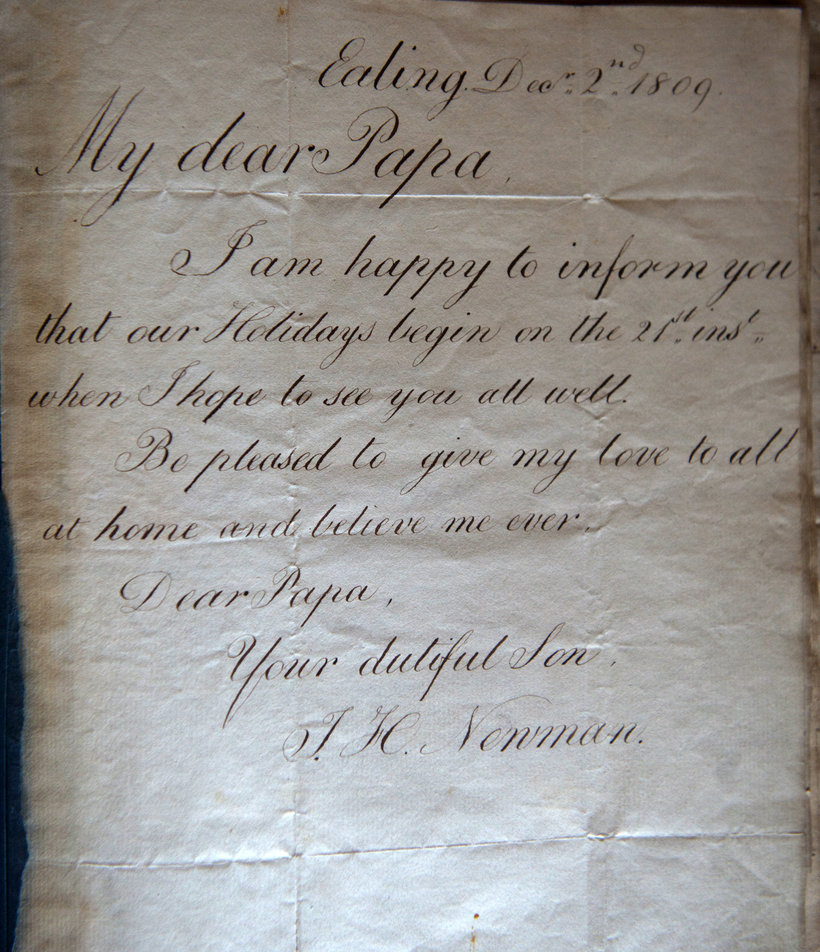

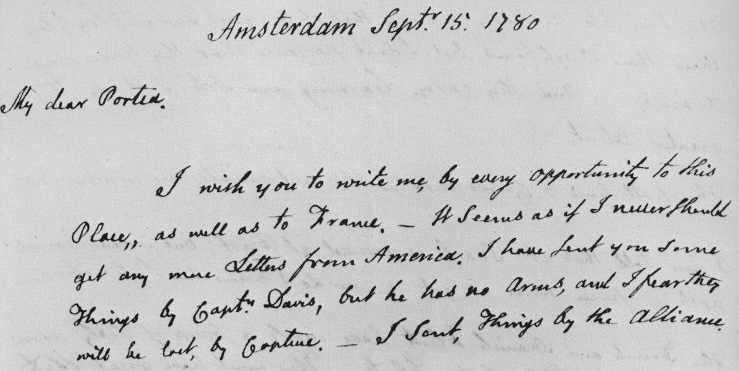

Yes, you can punch keys faster, but a key punch is a key punch. There is no connection with the formation of the letter and the word. Your mind is not making the sound, forming the letter, sending it to your fingertips to reproduce that sound on the page. When a boy writes by hand, he, not a machine, forms a sound, creates a sound, and then a WORD. He makes his own words become flesh, and, thus, in the words of J. R. R. Tolkien, he becomes a “sub-creator” with God. (It is telling that Tolkien, in creating the alphabets for his peoples of Middle Earth, made their scripts reflect their natures; the straight, rigid runes of the dwarves, the flowing, graceful script of the elves. It is true that a script reflects the nature of the person or people using it. This is sad news for a culture that cannot write but only punch.)

I became serious about my penmanship in fifth grade when we were studying the Declaration of Independence. I saw those signatures; bold, decisive signatures of bold, decisive men who were not ashamed of their deeds and knew the value of honor. They weren’t afraid to let anyone know their names. John Hancock even said that he wrote his name so boldly so “the fat old king could read it without his spectacles.” And to this day, we use Hancock’s name as a synonym for a signature. (And to this day, I take care to write my signature neatly, even on a credit card receipt. It is I, Robert B. Greving, who is paying for this, not some meaningless number.) It is also curious why we take umbrage when someone mispronounces our name, yet take so little care in writing it—expressing it—ourselves.

That brings me to my second reason for the teaching of penmanship: it is a creative act. It is an act of beauty and Beauty is one of the aspects of God. Penmanship must be done slowly and carefully. It forces attention to detail, order, and deliberation. We even use the expression “dot your ‘i’s’ and cross your ‘t’s’” as a metaphor for taking care in a matter. It is hand craftsmanship in a literal sense, the natural scholastic counterweight to a boy’s innate precipitate nature.

If writing is an art, so is the act of writing. We have the boys take art and music class, and rightly so; why, then, balk at a discipline which is another form of beauty and which bridges the gap between the visual arts and the literary arts? Penmanship unites composition (forming our thoughts) and art (the creation of beautiful images). It is one art form that, barring physical or motor-skill impairments, a boy can learn to do well, and one that stays with him the rest of his life. It is also personal whereas computer fonts have all the personality of, well, a computer.

I find letters and scripts fascinating. There is beauty and joy in penmanship. There is the Georgian grandeur of a capital G; the precision of an i well-dotted; the defiant sword thrust of a t well-crossed; the sliding sibilance of an S; the effiness of an f looking like teeth biting down on a lip. Then there is the slash-swoosh-slash of a Z. Could Zorro have done what he did if his name began with a “W”? I think not.

Penmanship also fosters silence. Concentration is the door to contemplation. Remember the medieval monks and their manuscripts? In former days, schools and libraries were oases of silence; today, with all the screens and graphics and “click-clicking” of keyboards and “mouses,” they seem more like a cross between a video arcade and a chicken coop. If studying is a form of contemplation, or at least a stepping stone to it, then its two greatest obstacles are haste and noise.

Our culture, especially our communication, is frantic. Instant messaging and texting, accompanied by images flashing on screens, buzzes, beeps, chirps, and rings have shredded our relationships with others, even our very thinking. Is it any wonder we can’t study or pray? This is why natural history is so important at The Heights, especially in the lower and middle school. You can’t hurry an egg hatching or a plant growing, and they do it in silence. Penmanship links nature and the classroom. In fact, Platt Rogers Spencer, the father of American penmanship who gave his name to the “Spencerian script” that would be the model for writing for so long, based his script on the graceful ovals and curvatures he saw in nature. I would advocate a boy practice his penmanship for ten or fifteen minutes before studying. It will quiet his mind and slow his thoughts. (And if you are ever in a “huffy” mood, take some time to copy some verses from the Bible slowly and neatly; you will soon gain composure and perspective.)

A sacrament is a visible, tangible sign for a reality that is otherwise invisible and intangible, and there is something sacramental in writing by hand. A word, a thought, an idea is in our mind, and we give it form and flesh when we put it on paper. Should we not give it the care and attention it deserves?

It is odd that an age so concerned about the “practical” in education should abandon such a practical discipline as penmanship. Odd, but not surprising. For by “practical” we mean that which is efficient, fast, and impersonal. There is no place for beauty, silence, and deliberation. We can’t forget, though, that a human being is not simply a mind; it is a soul united to a body. To educate the soul, we must use the body. What literally connects us to words is the hand, that is, penmanship. By training the hand to form letters and words with care, we can train the mind to use words with care and appreciate beauty. That should be a main concern with any education.