I. Some Clarifications

You might be thinking: How does anyone stay young? Before I try to answer that question, I suppose I should say, right at the start, that I don’t mean young, like, well—the young. For the last fifty years or so we’ve seen an embarrassing adulation of “youth” that has at its heart an imitation of them, a courtship by indirect (or direct) flattery. Young people still set the standards in fashion in regards to clothing, cars, music, language (especially slang), film, entertainment, even, madly enough, food. The markers that for generations, even centuries, have demarcated the land of adulthood with its freedoms born, ideally, from grave responsibilities have been breached and discarded. Today toga virilis is an upscale brand of men’s shoes. Our romantic inheritance of idealizing the young seems infinitely merchandisable.

There are, of course, many things about young people that are clearly admirable: their energy, their wonder, their laughter, and especially their idealism. Such reserves can do amazing things. Yet because young people by definition lack the perspective of many years of living, these capacities can go off track, at times with harsh consequences. Hence the need for guidance, for mentoring, for real friendships with more mature souls. Parents, siblings, and teachers can all provide much-needed context, even wisdom, so that the energies in the hearts of the young don’t double back and inflict unnecessary wounds, sometimes lastingly so.

This is where teachers come in. While not their parents (but with delegated authority from them), teachers can assist their students in exercising judgment by helping them become self-aware of the unique privileges of their own humanity. Allied with a deep sense of responsibility for the gift of life, teachers can thereby contribute to that opening up of a student’s inner life by instruction in the excellencies of soul (the moral, intellectual, and theological virtues) that help us flourish in this life and, with grace, in the next. This task of teachers (in many guises) is necessary because the riches of being a human person aren’t self-evident; in fact, those gifts are endangered by our fallen state, whereby the very powers that would preserve us and the human race itself can also work to our destruction.

The situation I’m describing isn’t solely the burden of young people. It’s the challenge of every soul that comes into the world and strives towards maturity. This naturally includes teachers. When we forget that we too must daily climb towards a higher, more interior-driven, more reality-shaped relationship with others and the world around us—we can find ourselves sinking into that netherworld of fakery, infamously parodied in the 1980s film Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, where a teacher catatonically asks a question repeatedly, lifelessly, until the main character in the story tosses off a correct answer. This is to use the legitimate skills of presentation we may have developed to hide our lack of preparation, which often means that we’ve failed to show up for class, despite all appearances to the contrary.

II. Keep Digging

In order to keep our teaching fresh, enlivened by enthusiasm—better yet, by an ardor for our subject—it’s important to keep learning ourselves. Our free time during holidays and summer break should be opportunity for wider or deeper reading into our subjects. Our library at home should be well-stocked. We should have a map in our head of every used bookstore within fifty miles of us. We can make this work with our family too by venturing out to places of historical interest and actually laying eyes on what we teach. For instance, more than a decade ago, while visiting New England, my family and I spent a day at Walden Pond and the town of Concord, Massachusetts. We walked around the most famous pond in American literature whose vistas are largely untouched since the 1840s, when Thoreau lived among the woods and later wrote a lyrical account of great originality about the essential things of life. My colleagues who have a similar number of years in the classroom as I do try to follow this path: deepening our knowledge of what we know by expanding the horizons of what we don’t and heading out to the undiscovered country. We try to leave the digital world behind us in such endeavors.

A transactional view of things has its place, but it’s a lousy philosophy. I say this not out of some professional or personal pique, but because it’s the way the world is. Iain McGilchrist’s The Matter with Things: Our Brains, Our Delusions, and the Unmaking of the World (2021) is a demanding read, but it makes clear how our brain’s hemispheric division—beneath our conscious perception but amply demonstrated by neurology—integrates a view of the world with certain tendencies.

McGilchrist shows us how the left hemisphere is the great quantifier and manipulator of reality, a major driver of our science and technology; it narrows down to certainty; it sees things as “isolated, discrete, fragmentary.” The right hemisphere “tends to see the whole”; unlike the left hemisphere, the right understands “metaphor, myth, irony, tone of voice, jokes, humor more generally, and poetry.” The left hemisphere is “superior for fine analytic sequencing” and “more complex syntax.” The right “is better at seeing things as they are pre-conceptually—fresh, unique, embodied, and as they present to us.” Both ways of seeing are important. But when the left hemisphere articulates into a philosophy of the world, it necessarily robs reality of its richness. It crushes a perception of the whole, which is never a mere summation of parts. As McGilchrist points out, the lyric poets and most of the great scientists agree on this vital point: reality is endlessly, densely rife with meaning and implication, and therefore our way of understanding it must accord with its mystery. So, too, must our manner of teaching.

All of the above is crucial because good teaching always has something of the excitement of a first-encounter. For veteran teachers, reading and exploring, lengthening our personal reading list, getting out-of-doors, literally and psychologically, is essential not only to avoid fossilization but to bring an illuminating passion to our classes. In the manner of its acquirement, this passion for new learning shouldn’t be noisy or superficially dramatic. It will be manifest to our students in our patience, our sense of perspective, our love of how the details of our subject show forth the logoi of creation, witness to God’s infinite fecundity, and his gift to us of being able to behold these wonders. Reading judiciously will keep our contextual comments grounded in detail; and, likewise, help the details of our subject become illuminated by a grasp of the whole. None of this comes at once, of course. None of it comes by chance, either.

III. Stake Out New Territory

We haven’t entirely left off reading. (Can we ever?) One way to be a more effective veteran teacher is to study a new area of our subject specialty or one relevant to it. As a former chaplain at The Heights once told me, “read around the subject” to see it from fresh perspectives. A metaphor for this is to consider in your mind putting fences (wooden split-rail, please) around areas you’d like to learn more about and, in the process, reading deeply into specific areas of said subject much like a strong fence needs sturdy posts sunk deep into the soil to keep it standing. This can work in any of a thousand or more ways: In getting ready to teach a Dickens’ novel, read Peter Ackroyd’s London: The Biography (2000) or his Thames: The Biography (2007); or read one of the great biographies of Dickens, or one of his contemporaries such as Alfred Lord Tennyson, to get a comparison of literary lives, their glories, challenges, and legacies. The split-rail fence reference is actually more to the point than it may appear. We don’t want to box in our knowledge; to distinguish is not to separate.

Despite the apparently endless nature of new things to be learned, there are parallels, contrasts, and new insights to be had with this type of study. It does, however, take effort—and years to acquire. You’ll primarily be benefiting your students, but in the end, you will feel the gain too. A freshness. A sense of reverence at the inter-connection of so many things. As well, bemusement at the irruptions in history and in the arts that cannot be easily explained. They give evidence of humanity’s spiritual nature, its exaltations evident in grand architecture, the fine arts, the seemingly endless array of the humble habits of daily living, and tragic distortions that have afflicted nations and darkened histories.

We also need to find ways to use our leisure time that is restful without being escapist. For over a decade starting in the 1990s, I took up deer hunting on weekends and vacations. It was something I’ve wanted to do since I was in elementary school in a Boston suburb and walked into the carpenter’s workshop of my best friend’s dad and saw two deer hanging from the rafters. I’ve hung up my bow some years ago, but I’m glad I took the time to get out in the field, and test my skill against such amazing creatures. The time I’ve spent in a tree stand—with a small book in my pocket, of course—was an opportunity to contemplate the beauty of God’s handiwork in the silence of the woods with its varied, seasonal beauty. When teaching poetry from the Romantics or reading the great American Transcendentalists or even, more recently, Thomas Merton, who had a keen appreciation of nature, I’ve come to enter better into their works thanks to my own hours spent in the woods. It’s helped my teaching. Out in a wintery forest, you can see how all things are held in silence, how they in fact flow from God’s hidden closeness as sustainer of all being. Words, and the crafting of words, should come out of a similar silence stilled in wonder before the world.

It’s best to have some kind of plan, but people are different and there are many ways to broaden your way in the classroom. As well, having a friend to share in these forays into new subject areas, sports, wilderness activities, hobbies, and so forth is always helpful. What’s important is that these added junkets into something new to you should have some relationship to what you teach, if only peripherally. That’s actually the whole point. Teachers who are interested in many things almost invariably become excellent at their core subject because they see the world a little more comprehensively than they would otherwise. One of the best “tests” I have come across for what makes a good teacher came from something Jonathan Kozol wrote a few years back: Would you want to sit next to this person on a cross-country flight? Always be learning. It’s the only way to teach.

IV. Physician, heal thyself (Luke 4:23)

The meaning of this ancient proverb (ancient even in the time of Jesus) in the context of Luke’s Gospel centers around groundless charges of hypocrisy that were leveled at Jesus during his ministry, particularly in his home town of Nazareth. With Divine irony, a similar remark (Matthew 27:42) will be directed at the Messiah on the cross, the Savior of the world apparently unable to save himself. But for our purposes, we can take it in its original meaning: reminding us not to ignore our spiritual lives while at the same time urging others on to a path we do not follow. Obviously, we want to grow in the love of God as well as help others do so. But that means doing the first with sincerity so that—even with our defects and imperfections—we can teach our students from an overflowing of our interior life. Like a good steward, we can take from what we learned yesterday or even twenty years ago, and bring it to this group of students today, right now. The moment leavened by years of experience, even, perhaps, by our mistakes, will be particularly enriched. This sincerity will also help us see and share the wonder of life to those we teach, and thereby battle against the “flattening out” of our society whose secularization has nearly vanquished a sense of mystery, the splendor of God’s truth in God’s world, which is his gift to us.

I should say here I am heartened by my colleagues who have dedicated decades of service to The Heights. They are men of deep Faith and make exemplary efforts to live a life not just for others, but for others out of love for God. It’s an honor and an inspiration to work alongside them.

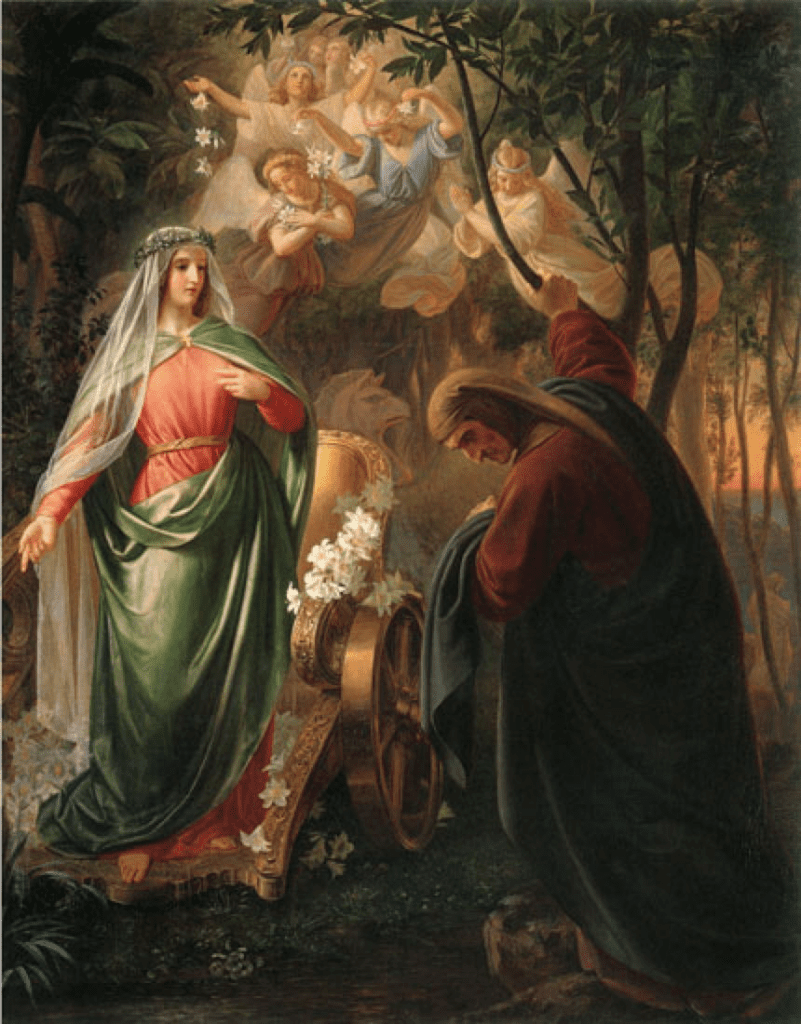

I would say, finally, that a life of virtue is a life preparatory for contemplation, the foretaste of that complete, unending beholding that is heaven. It’s important to avoid moralism, as Benedict XVI taught us so well. When students are stilled in concentration of an object, in art class, mathematics, or literary studies, this is a natural precursor and helper in a life of prayer. All excellencies are, by definition, goods in themselves; yet they only fully disclose their nature and purpose by the light of a supernatural faith in the Gospel. I sometimes think young people intuit this on their own. Their playfulness, when rightly grounded, reminds me of Dante’s presentations of the Heavenly Pageant at the end of the Purgatorio: all the virtues are allegorically embodied dancers, rejoicing in the liberating joys of serving God. There’s nothing dour or puritanical in Dante’s vision. It’s one of liberation, happiness, celebratory finesse before the giver of all good gifts.

As teachers get older, we should remember St. Augustine’s remark, “God is eternally young.” This is at times difficult to remember when youthful frivolity is in the air. But remembering that the proper goals of life are for our happiness and flourishing is a sure way to keep a youthful spirit allied to the sobriety of true wisdom.

So how does anyone stay young? I would say by following the advice of Psalm 1:3: “And he shall be like a tree which is planted near the running waters, which shall bring forth its fruit, in due season. And his leaf shall not fall off: and all whatsoever he shall do shall prosper.” Those “running waters” are, of course, an image of grace, without which we can do little over a lifetime that will amount to anything much before God. So the arc of a life dedicated to teaching must draw on something higher than earthly ideas, however noble. We must befriend God, who is always a source of renewal on the way that leads to Him here and now, and in the final banquet of heaven. Teachers who want to carry their years in the classroom lightly, full of joy and prudent circumspection, despite challenges now and again, will remain youthful because they know where to find that Well whose waters never run dry (John 4:14).