Consider a puddle. Not a lake or a pond but a small, oval, shallow indentation in the ground containing rainwater, scattered dirt, and perhaps a smattering of storm-blown leaves. A collection of clouds hover above the concrete below, the reflection of the trees overhead; or in the city, a Mansard roof leans in from the left covered in copper, although the puddle could not tell you that. It takes a split second to see all of this or none of it and in that same moment, likely blocking out all that is held within, we make a choice.

Perhaps we note the puddle when we are still a way’s off and our feet adjust accordingly, veering left or right to avoid what lies ahead, or perhaps, our eyes already averted by some distraction in our hands, we simply march forward and meet the standing water with an emittance of dissatisfaction and mud-spattered pants, our confidence shaken by this seemingly innocuous pool that now sends a shiver of rage through the spine, a day already set off-kilter by the burnt toast at breakfast, now torched by the quench of an unplanned contradiction. I knew I should have brought my galoshes! Things can unravel quickly, a storm begins to brew.

But take another view: that of a child, a toddler, who sees the puddle from afar and races toward it, pudgy arms pumping, the tips of the shoes barely clearing the ground, every rushed step seemingly bound to end in a sprawl upon the ground, but somehow staying up, pushing forward; a grin spreads across the little face, squeals of joy leap from the heart, and soon the splashing and stomping commences. Other little ones might stop when they reach the puddle and look into it, staring into its depth—at what, the jaded adult might wonder, come on, it’s time to go. But the child is entranced and slowly reaches into the puddle and picks out a sodden leaf, more brown than yellow, examining it before mournfully looking back at the little paradise inside the puddle as he is pulled away, “not now, maybe tomorrow,” a little lie cloaked in the present rush of time slipping away.

G. K. Chesterton opined that we achieve our personality’s full potential at the age of six and spend the rest of our lives trying to get it back, and walking around American cities and suburbs, one finds it difficult to disagree. It is rare to hear real laughter on the streets, passersby eagerly avert their eyes, and those with dogs cross the street. It’s a far cry from the excited waves and “hi”s shared by my 18-month-old, who gleefully greets everyone she sees. This is not to castigate adults or victimize those who need to complete tasks but rather to reevaluate how we view seemingly mundane things. It would be odd, of course, if adults raced towards puddles on a regular basis and romped and stomped and stamped in them. But adults are also missing out if all such puddles are seen as mere inconveniences. In “growing up,” somehow the joy of a child is lost in the attempt to flee childhood, yet all the negatives seem to remain.

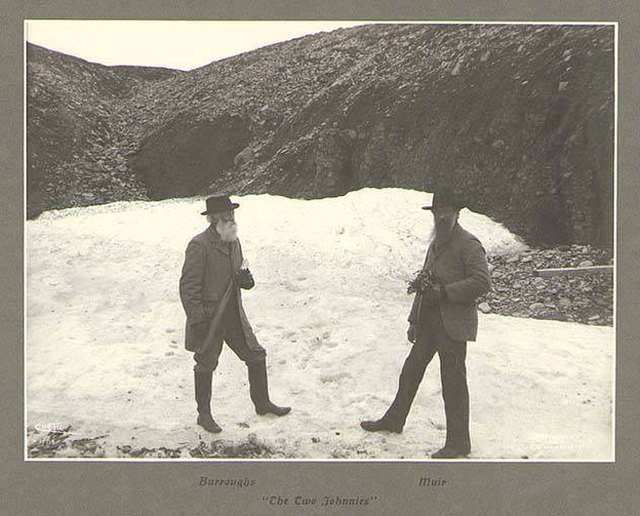

Recently, I ran into a John Muir line somewhere (perhaps on a summer trip to the Smokies) that buttressed a thought I have pondered for sometime: “Never go to Alaska as a young man because you’ll never be satisfied with any other place as long as you live.” As adults the temptation is always to share deeper loves because we feel that as we have already appreciated the road to that love, our younger steads might as well hop right in and enjoy the same. Skip the boardwalk through the local swamp and jump right to some rocky peak with existential views, skip the squeaky ski lifts and icy slopes of the East and head straight for the heated gondolas of Steamboat Springs, skip Tolkien’s Letters from Father Christmas and jump right to that trilogy he wrote. We should not then be astonished when things begin to go awry—when little novelties lose their joy because they do not provide the pleasures that deliver adequate “dopamine to the dome” as a ski-bum friend used to describe certain lines down the mountain.

This is not to say that exploration and “pushing the boundaries of possible” are not worthy—on the contrary, embracing the little novelties of everyday life allow us to not live for the vacations ahead, while preparing us for greater adventures when the opportunity arises. On a trip to Ireland several years ago now, I commented to an expat friend living in Galway that I was surprised not only by the constant stream of Irishmen marching up Croagh Patrick but also the empty churches, even on Sundays. She laughed and said this was only natural: that the Irish believed they could live as they wished and then cap it off with a great act of penitential contrition at the end of the fiscal year. This may strike us as surprising, but in reality, it is exactly how many of us live our lives, simply pining for the two weeks at the beach in August and forsaking countless opportunities for adventure and enjoyment in between (or, in the case of Croagh Patrick, missing out on countless opportunities to offer mortifications, little novelties in their own right). The tiny habits of joy we practice, or the little novelties of celebrating feast days, keep our eyes alive along the way to bigger things.

These little novelties, or “local novelties,” are a delicate matter as, even definitionally, we encounter two seemingly opposing sides: on one is the quality of being new or unusual (I imagine we all recall the almost obsessive and redundant use of the word “novel” to describe the coronavirus which we all know as COVID-19), and on the other is the small and inexpensive trinket. The key to holding onto local novelties is never losing interest, or at least, constantly renewing interest in such things. This can be accomplished by living seasonally—both relating to the weather and liturgically—and by getting to know things better. Take Christmas trees: in most American metropolitan areas, we can acquire these trees for exorbitant prices if we have not already sold our souls in favor of the abomination of artificial ones. Mere weeks after attaining them, we are prepared to dispose of them, forsaking a full month of celebration and festivities, ending a season in January that rightfully ends with Candlemas on the second of February. Christmas thus passes in a flash of great expense and little enjoyment.

But strike that, reverse. What a season to practice the art of local novelties. Perhaps, the first weekend of December every year, we go and cut down our Christmas tree, whether at a farm or forest, the latter more exciting but perhaps less practical. We leave it bare for a week and then add lights, then later add ornaments, then later the presents start to appear beneath the tree, little by little. On the evening of the fifth of December, we put our shoes out for St. Nicholas, we listen to Advent music in Advent and save the Christmas carols for Christmas. Little gifts, such as books, are given on Epiphany. Each subsequent Sunday of Advent is celebrated with slightly more fervor—not approaching the Christmas feast, of course, but danishes instead of doughnuts or cocktails instead of wine. Something tied in with the day, something to look forward to, something special. In this way, we prepare for Christmas as we prepare for a wedding: gradually, little excitement by little excitement—a proper hors d’oeuvre titillates the appetite, it does not overcome it, it keeps us wishing for more. Now extend this to the four sun-driven seasons. For example, on the small scale, some friends and I have an–admittedly, recent–tradition of summiting Old Rag Mountain to watch the sunrise on the shortest day of the year, and on the grand scale, the opening of pools on Memorial Day rings in the warmer weather of summer. But we need not limit ourselves to the whims of others; while most of us are city or suburban-dwellers, cocooned from the elements by four walls, a well-shingled roof, and central air, we can still tap into the gifts that each season brings. Soon we will start reawakening little joys found in every season, every month, every week, every day.

The development of such local novelties is, however, based on a structure that must already exist. Routines create a safe haven that we can count on and are necessary for the simple joys to be embraced, though we must also be careful not to allow the routines to overcome our joys. Nor can we allow novelties to become slave to routine. Novelties only naturally lose their intrigue when we overuse them or our eyes are caught by shinier things or more complex issues. Thus, the idea of domestic novelties extends to the more foreign ones. There comes to mind a western romance series that my sisters used to enjoy titled Love Comes Softly—the story I cannot share as I do not know—but the idea behind the title rings true. We can do our children a disservice if we take them to far away places before they have developed an appreciation for the local. Love for things must be grown and fostered, and love is a constant giving of more.

That child entranced by the puddle is in love with the local world around him and that man pulling the child away faces a crisis because he has stopped caring about the local. Moreover, he is teaching the child—who will no doubt later be placed in front of a screen in an attempt to entertain—that the shiny moving pictures or cheap toys that make noises are more interesting than the sodden leaf. There is no joy in that leaf because he cannot see, he cannot engage his senses anymore without needing bigger, better views, seeing more things, faster, now. But recapture that appreciation of the local and the foreign will become all the more impressive.

Writing with an eye towards our nation’s national parks, Edward Abbey, the anarchist/environmentalist of southwestern fame, wrote in his delightful Desert Solitaire:

…the chief victims of the system are the motorized tourists. They are being robbed and robbing themselves. So long as they are unwilling to crawl out of their cars they will not discover the treasures of the national parks and will never escape the stress and turmoil of the urban-suburban complexes which they had hoped, presumably, to leave behind for a while.

Drag a child around from place to place, ‘scape to ‘scape, and they will become overwhelmed and underjoyed—theirs is naturally an interest in the small; “big picture” means nothing and the details everything. How many people take a picture of a scene before looking? So many that I think a fun modern art show would be photos of people looking at their phones in gorgeous places—I remember sharing the idea with my wife this past summer as we walked by the Smithsonian Castle in downtown D.C., just before passing a family of four on a park bench all on their phones. In the shade of a tree across the street was a couple holding hands but looking at their phones. Another couple was huddled in the shade of a portico, again, both on their phones. Is this the way to find joy?

But try a deep dive into one spot, perhaps several days moving by paddle or foot, or a visit to an art museum to see a specific selection of paintings, and one will not only appreciate the experience but be better for it. Further, adults, who can appreciate the grand, only do so because of a learned appreciation for everything the grand encompasses. What makes a view or painting masterful is very much reliant on all the parts that make it. And to truly benefit from the outdoors—and from art, novelties, etc.—we must allow ourselves to be removed, if only momentarily, from the norms of the everyday.

From this removal, not only is the present enhanced, but we develop a greater appreciation for the structures and habits which govern our daily lives. The structures cease to be inhibitive as we discover that, appropriately disposed, they help us flourish. In this way, joy and struggle, novelty and structure, are intertwined, necessary components of a life firmly rooted in the present with eyes set on an eternal goal. The toddler by the puddle is a joyous soul, and by slowing down and following the little one’s lead, we too can attain the joy of a child, loving every day as if it were our last.