Tuesday, 24 May 1763:

The rain had stopped before sunrise, but the sooty-film it left on the cobblestones off Inner-Temple-Lane made Boswell nearly slip into the mire twice. A third time, and the thought of sliding into horse-dung and God knows what else might have warned him off, ill-omened, to be sure. But Boswell wasn’t so easily put off today, so he watched his footing, while the sounds of carriages and whipped horses and carts and jouncing coaches filled his ears with something like a medley, a humming tune of city life he relished, sometimes wickedly. His silver-buckled shoes were scraped more than he could tolerate, but that came with walking. He should have gotten a coach, he fretted. But he was almost there. As he turned a corner, he saw No. 1’s celery-green door, its brass knocker looking like a spoon big enough to feed a baby giant.

He lifted the knocker, and it fell with a thud, like a body dropping to the floor. Then he heard someone coming to the door, the steps deliberate, measured, ominous. Boswell wiped his left foot on the curb, and looked up.

The man who opened the door to Boswell that day in May was, of course, Samuel Johnson. Born in 1709, in the midlands of England, by the 1760s Johnson was already widely celebrated as “Dictionary Johnson,” the man who nearly single-handedly wrote the first comprehensive dictionary of the English language. His career as a writer was certainly impressive, its rise from obscurity powered by the success of his dictionary alongside poems that caught the attention of London’s literati. Over the years he would write more poems, and prefaces, pamphlets, and short biographies, in addition to editing the works of Shakespeare. But it was the dictionary that in 1762 inspired a young King George III to award Johnson a life-long pension for his labors in furtherance of their country’s literature.

Johnson’s work represents a high-water mark in literary history for its classical genius with roots deep into Western antiquity. Few could match the excellence of his work, and pretty much no one could replicate the oddities of his life—or want to.

Johnson’s mother meant the best for him, but when she had a local woman be his wet-nurse, she unknowingly exposed her son to a tubercular disease of the lymph glands commonly known as “the king’s evil,” as it was thought that a touch of the royal hand might cure it. When Johnson was a child, he and his mother traveled to London, but Queen Anne’s touch proved ineffective. So did the doctor’s efforts, who, when Johnson was an infant, cut deeply into his neck glands to bleed them, leaving lasting scars on his neck and face. The disease left another legacy: Johnson was deaf in one ear, and blind in one eye from his earliest years.

Despite these setbacks, he proved a brilliant pupil, and eventually made his way to Pembroke College, Oxford. After thirteen months, he withdrew due to an inability to pay tuition. He went back to his native town of Lichfield to his parents where his father ran a bookshop. Family finances were never steady. Melancholia, depression we would say today, stalked Johnson steadily. “The Black Dog” he famously called it, refusing to give it sway over him.

In his twenty-sixth year, he married a widow nearly twice his age—Elizabeth Porter—and after failing to set up a school in Edial, he went off nearly penniless to London accompanied by one of his few pupils, David Garrick who in a decade or so would become the most acclaimed Shakespearean actor in England. Johnson’s success took a bit longer amid the cheap byways of Grub Street, a virtual factory of hack writing for men who earned their next dinner from their pen.

Johnson’s wisdom was curated in his own sufferings. Aside from his physical ills, his melancholia made regular work difficult. But work he did: in the 1750s, while putting together his dictionary, he wrote essays twice weekly for several years rich with practical advice expressed in a style not always simple but invariably graceful and refined. He rarely edited these pieces before they went to press. He once composed a piece on the dangers of procrastination while a boy stood by, waiting to take the sheets to the printing press for publication.

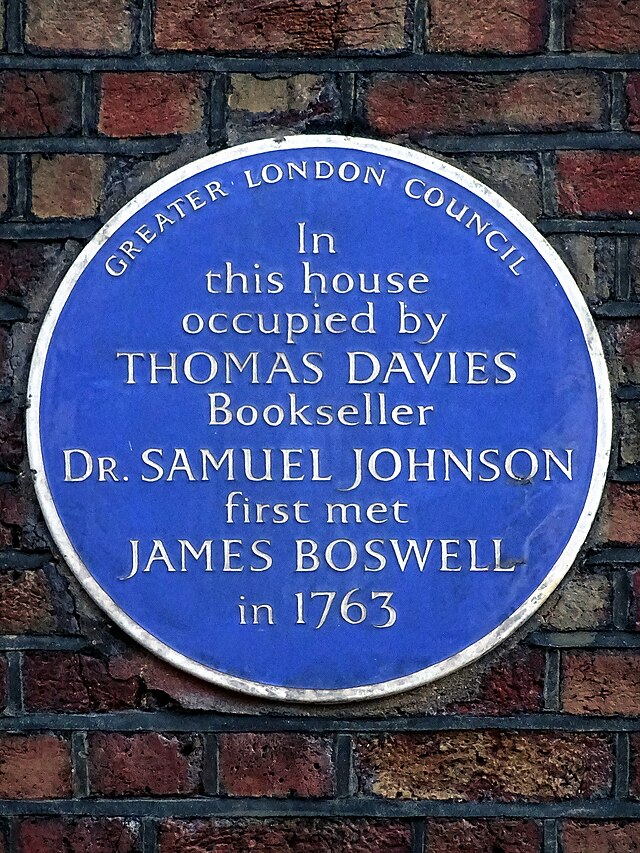

On May 17, 1763, a twenty-three-year-old James Boswell met Johnson for the first time in a London bookshop owned by Thomas Davies, a sometime actor. Boswell was the son of a Scottish Laird of Auchinleck. His father was a successful lawyer and a member of the Court of Assizes, a practical man who wanted his son to settle down into a life in the law, after which he would tend the family estate that encompassed nearly twenty square miles. Boswell was everything his father wasn’t: mercurial, witty, a drinker, a social climber, an impressionist of considerable skill, in short, the life of the party whose particular skill was bringing people out of themselves. This latter talent—alongside an ability to write up a scene or a character with fluency and imagination—made him perfectly suited to write the first great biography in English literature.

The two men had much in common: Boswell and Johnson were both subject to bouts of melancholia; they both had fathers either difficult to relate to, though Johnson’s father deceased early in his life; they both loved talking about literary matters as many men today love talking about sports. They also had many differences: Boswell came from a noble Scottish lineage, Johnson was an English commoner; Boswell had four children with his wife Margaret, while Johnson was a childless widower; and though Boswell was no dummy, Johnson’s intellectual abilities were clearly extraordinary. Their temperaments contrasted as well: Boswell was restless, even flighty, while Johnson was phlegmatic, inclined to late nights and mid-day breakfasts.

Eighty-percent of Boswell’s biography of Johnson chronicles the roughly two decades they knew each other. As such, it’s crammed with literary anecdote, witticisms of furious “mic-drop” megatonnage, letters (lots of them), and what seem like transcripts of conversation, often as not from some tavern where, in the glow of a crackling fire, Johnson held forth. Boswell gathered in his memory and notes each literate broadside as if it were a jewel about to be tossed to the floor, lost in the noisy chatter of London’s literate class:

*On Garrick’s successful acting career: “No wonder, Sir, that he is vain; a man who is perpetually flattered in every mode that can be conceived. So many bellows have blown that fire, that one wonders he is not by this time become a cinder.”

*On his being partial to being with young people: “I love the young dogs of this age: they have more wit and humor and knowledge of life than we had; but then the dogs are not so good scholars.”

*On his staunch Tory politics: “…the first Whig was the Devil.”

*On Johnson’s having argued for some time with an opponent, who said, “I don’t understand you, Sir,” upon which Johnson observed, “Sir, I have found you an argument; but I am not obliged to find you an understanding.”

*On Lord Chesterfield, his would-be patron: “This man I thought had been a Lord among wits; but, I find, he is only a wit among Lords!”

*On his love for dinner and conversation in a tavern: “There is nothing which has yet been contrived by man, by which so much happiness is produced as by a good tavern or inn.”

Due to Johnson being a generation older, there is something of a father/son relationship to their friendship: the older, wiser Johnson reassuring the younger man on his choices of career and marriage. Yet Boswell helped his friend in immeasurable ways even as he helped himself to literary fame in his long-standing plan to write a biography. Johnson, in his sixties, acknowledged Boswell’s plan to write his life, and not only concurred but cooperated in the endeavor. Despite their failings (there were many on both sides), Boswell’s friendship with Johnson has an unflagging energy to it that’s inspiring, like a spring morning. Even amid the foul streets of London in the foulest of weather, they were delighted to see each other; even given Boswell’s sometimes ridiculous pestering or odd line of questioning (he once asked Johnson what he would do if he were stuck in a castle alone with an infant; “Why, raise it, Sir!” was the response). In periods in which one or the other suffered from melancholy, they supported each other with words of encouragement, the kindness of genuine concern. They brought out sides of each other’s personalities that, had they not met, might never have surfaced at all.

Thomas Merton, the twentieth-century monastic writer, once said “True friendship is a kind of singing.” If so, then the ability to stay on key when your friend misses a note, the sense that a good friendship is worth careful tending in and of itself, and given what you value in common—singing from the same page, so to speak—truly characterizes Boswell and Johnson’s friendship. They forged a relationship that had its challenges but talked for two decades about everything from peacock brains (in Johnson’s analogy for luxury goods in a free market) to the high questions of the soul’s destiny after death. Their friendship took on the world: art and history, pickles and pastimes, ghosts and literary forgeries, the quick and the dead, this life and the next. Boswell wrote the book to prove it.

Boswell and Johnson parted in London, at Bolt Court, on Wednesday, June 30, 1784, with manly but heartfelt restraint. Johnson’s last words to his friend, among others, included: “Nay, Sir…Endeavor to be as perfect as you can in every respect.” Boswell had gained a unique intimacy with a mind that he once compared to a Roman Coliseum, so vast was its mysterious, classical grandeur.

During the following autumn, Johnson’s health swiftly declined after many years of chronic illness. The portrait painter Reynolds would be executor of his estate. The bulk of it would go for an annuity to Francis Barber, a freed slave from Jamaica whom Johnson treated as something between a son and a servant, but always kindly. Around his deathbed hovered doctors and friends and fears and dark thoughts of judgment and damnation. As the weeks passed, his gradually failing heart caused many sufferings, including what was called dropsy, a collection of fluid in his legs that caused him much distress. When he asked his physician, Dr. Brocklesby, whether he could recover, and the answer was no, not without a miracle, Johnson swore off any further opiates so he “could render up” his soul “to GOD, unclouded.”

He died around seven in the evening, December 13, 1784, with no outward drama. In the last days of his life he expressed a deep and renewed faith in the redemptive sacrifice of Christ for the sins of the world. The day Johnson died, a Miss Morris, a daughter of a friend, begged Frank Barber for admittance so she could receive a blessing from the dying man. Upon her entrance, he turned towards her from his bed, saying his last words on this earth, “God bless you, my dear!”

Tuesday, 17 May 1791

Boswell sent the last sheets to the printers with a feeling of freeing himself of a terrible weight, attached by a chain forged by his own ambition. Seven years after Johnson’s death the biography was finally finished. Twenty-eight years to the day they met. That he was not in London when Johnson died hurt like a wound for which there is no salve.

He went for a walk, bundling up in the still damp morning. But he wasn’t thinking of his property or his books or even his deceased wife or his sometimes-wayward children. Instead as he walked into the garden on the southeastern side of his home, he thought of that bright day in July years ago on the Thames when he was in a sculler with Johnson. The great waterway opened up the horizons of the city with unusual splendor. He had asked Johnson as the wind made the man’s hat flutter whether a knowledge of the classics was essential to a good education.

“Most certainly, Sir,” said Johnson, “though it may not help this boy row any better if he could sing the song of Orpheus to the Argonauts, the first sailors.” The boy looked up.

“What would you give, my lad, to know about the Argonauts?”

The boy answered, “Sir, I would give what I have.” Johnson gave him a double-fare.

They continued rowing into the sunset and Boswell now realized he was that boy, and had given what he had to know this incredible bear of a man with a heart and a mind almost too much for the world. And so the world would know him too in those pages he so painfully gathered. But not like me, thought Boswell, not like me.

—Michael J. Ortiz teaches English in our Upper School. This past year, in reading Boswell’s The Life of Samuel Johnson with juniors and seniors, he wrote the journal entries that accompany this essay.