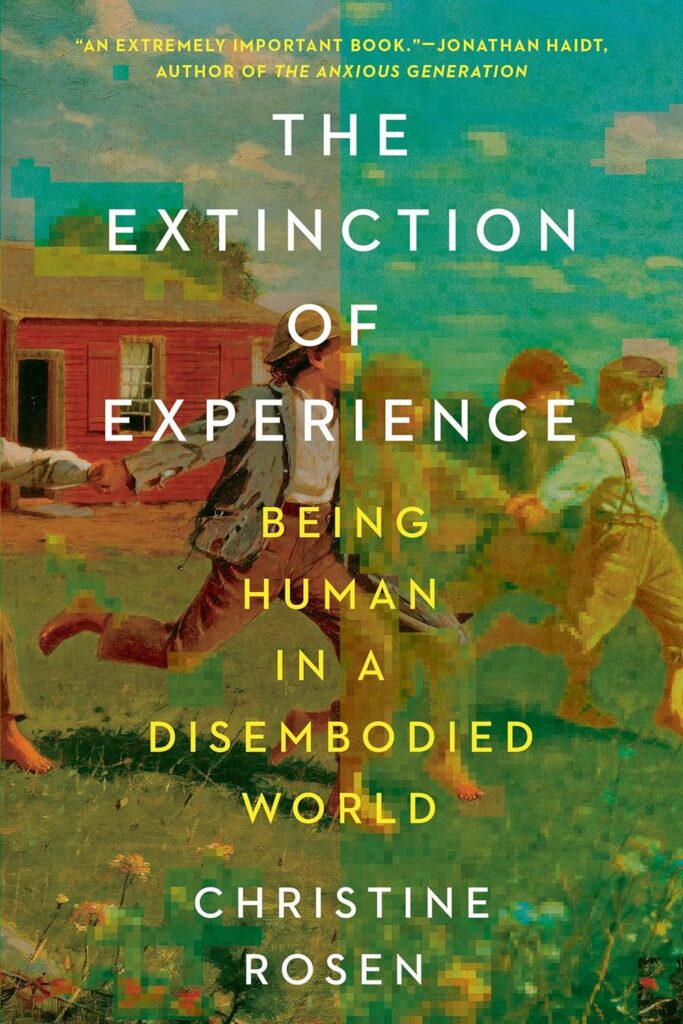

It’s been said that reading a translation is like kissing your wife through a handkerchief. What comes between changes the experience; something is lost. Today, as technology increasingly “mediates” our experiences, we are losing something too—perhaps our humanity. This is the argument of Dr. Christine Rosen, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, in her book The Extinction of Experience: Being Human in a Disembodied World.

Experiences are direct contacts between our human nature—our bodies, minds, emotions, and perceptions—and reality. Technology (and our desire for ease, comfort, and safety) has distanced us from it. It has happened often for good reasons, but more often for profit with no oversight or accountability, to the point that we don’t often recognize reality, we don’t want reality, and we can’t handle reality. We have become progressively susceptible to exploitation and manipulation. It is a sobering book.

It used to be, says Dr. Rosen, that “an experience was something … you enjoyed in your own physical body, in a particular physical space, at a particular time.” Now technology allows you to be (supposedly) almost anywhere at any time. It doesn’t even have to be your experience; you can use someone else’s. “We have forgotten we have bodies,” she says. Experiences are often inconvenient and full of surprises, as any Heights boy who’s been on a camping trip can attest. But technology has lured us with “seamless experiences.” “People won’t need to escape,” says Dr. Rosen. “They will replace their reality with one that is new and improved.” This allows our experiences to be controlled by others. We market ourselves on and are marketed by social media, which in turn devalues our experience. Memories are no longer something we reflect upon; they’re something Facebook reminds us of.

And we can ignore each other. “From birth we are wired to look at faces,” notes Dr. Rosen. “A body’s signs are among the things we know without knowing why we know them.” The ability to “read” another’s face, tone, and body language takes a lifetime, yet by replacing (real) “face to face” interaction with mediated ones, we are losing this skill. As a teacher for more than thirty years, I can attest to this. We’ve passed civil inattention and reached civil disengagement. “Attention is the rarest and purest form of generosity,” said French philosopher Simone Weil. By using screens to avoid confronting real people and real situations, we become less generous and less attentive as a glance around any public place—or even our homes—will show. While technologies such as Skype and FaceTime have advantages, they also allow us to become more manipulative and manipulated. Companies are introducing “real time photoshopping” so the face and voice you see and hear will be the one the other person wants you to see and hear.

After noting how we’ve replaced the face with the screen, Dr. Rosen next shows how we’ve replaced the hand with the mouse. Central to this is “embodied cognition … the link between one’s mind, one’s body, and physical experience.” Changing how we learn and do something in effect changes what we learn and do, as well as how we understand the world. “You who do not know how the mind is joined to the body know nothing of the works of God” was carved on a beam in the study of sixteenth-century essayist Michel de Montaigne. Penmanship and other ways of working with our hands, such as drawing, painting, and woodworking, form habits of mind that computers don’t: patience, perseverance, and diligence. Losing skills that have spanned millennia, we lose touch with those who have had those experiences. A boy can’t appreciate what pioneers sacrificed when he can “build a house” in a few clicks. Screen learning has also left out something vital for children—play, the proving ground for cooperation, effort, and fairness. When we don’t confront our own bodies with all their foibles and faults, we’re less patient with the bodies of others, outsourcing their care when the task becomes too onerous for us.

More than ever we hate to wait. We see speed as an improvement, yet, as Dr. Rosen says, “how we wait tells us something about who we are; about what we expect from one another and how, both individually and as a society, we understand time and plan for the future.” An agricultural culture knew you had to let fields lie fallow for production, but the culture today in which a second is too long to wait for a download has problems with patience. (Road rage, anyone?) She quotes a monk from the Abbey of Gethsemani in Kentucky: “What is the main cause of our sins? Convenience. … Seeking to make things easier. Or more entertaining.” Yet patience and boredom—unstructured and unmediated time—are essential for the development of creativity in children. Kids no longer play “make believe” because everything is believed for them. The sinister note in all this is that tech companies harvest and share data to feed these appetites. Now more than ever they are helping us to “kill time.”

Emotions are funny things. Unique, fleeting, and unquantifiable, they nevertheless give us insights into people and situations. They are much of what makes us human. “I don’t know: I just had a feeling.” What earlier clock technology did to time—regiment and regulate it—modern technology seeks to do for our emotions. Emojis, memes, and automatic responses require little thought or reflection and so limit thought and reflection. We can “ChatGPT” our empathy. As a result, we’re often told what to feel, as “digi-lante justice” testifies. And do you really want to know what the other person is feeling or want him to know what you are really feeling? Don’t worry. Companies are installing technology to monitor employees’ emotions. So next time you say, “Have a nice day,” you had better mean it.

Our pleasures were once our pleasures: things we enjoyed by ourselves as ends in themselves. But now they have become mass entertainment as a means to an end—“sharing.” They are filtered through the eyes and approval of others and through the management of technology companies. As we “share” our experiences (to the extent that technology allows us), they become homogenized. Travel was once about the unknown and unexpected; today we have “tourism” which is about the safe, controlled, and predictable. Your “experience” will be pretty much like everyone else’s. Many works of art reveal their secrets slowly; they require time, attention, and familiarity. You don’t get that from a laptop. The camera’s “eye” is not the “mind’s eye, ” and as a result we can suffer from “reality disappointment.” The real Grand Canyon isn’t as awesome as the images on Google; the real “Starry Night” isn’t as vivid as the picture on my coffee mug. Other pleasures have become mediated. Pornography “outsources” our intimacy; we watch someone else prepare a meal rather than make it ourselves; we pay to watch others play games instead of playing them. Of course, this is all being monitored so Apple can know—and prescribe—your pleasure.

I grew up in Fargo, North Dakota. I knew, and my parents knew, every kid on the block and for blocks around. The best cookies (aside from Mom’s) came from Leeby’s Grocery store. I still have a North Dakota accent and, in many ways, the place is still home to me. Technology has now replaced places with spaces. Our “communities” are online. Good civil societies had myriads of “third places” such as cafés, taverns, parks, and playgrounds, that developed organically and fostered neighborliness. “Spaces,” by contrast, are engineered and designed to remake a place into our own image. They replace pure sociability with quantified popularity, which in turn increases ignoring and intolerance of those we physically live with at home, at the office, or in the waiting line. We don’t have to learn to get along with others because we are now with those only with whom we get along. Like terroir in wine, a sense of place requires cultivation; it can’t be reduced to a formula or algorithm. Judging by the amount of loneliness and depression in our society, it seems we’ve been entrapped by the worldwide web.

Dr. Rosen is not a luddite. Technology has done marvelous things. But the surrender of so much of our lives to it so quickly has had a cost. When we allow the mediated experience to become the predominant one, often the only one, when we allow it to replace our judgments or tell us what to feel, then we have lost something of our humanity.

In her conclusion, she makes a suggestion and gives a warning. She suggests that, when it comes to technology, we look to the Amish and cultivate a robust skepticism. Ask the right questions: How will this affect our community? Is it good for our family? Does it support or undermine our values? She says, “When we choose to conform to the demands of the machine and replace human interactions with mediated experiences, we risk becoming more machine-like ourselves.”

Dr. Rosen’s warning is stark. She reminds us that technology isn’t neutral; it’s ambivalent. The values it promotes will be those of the ones promoting it. And they do it for profit. We are no longer users and consumers, but the used and consumed. She quotes software engineer and venture capitalist Marc Andreeson who dismissed those concerned about the effects of technology as “Reality Privileged.” Well, I like reality. I, like God, think it very good. G. K. Chesterton said, “The trend of good is towards incarnation.” When it comes to our humanity, it’s a case of use it or lose it.