American culture’s most successful export—since the late nineteenth century and continuing to today—has been technology. From Edison’s light bulb to the flight of the Wright Brothers all the way through the atomic bomb, the microchip at Bell Labs, and the internet connecting UCLA, UC Berkeley, and the Pentagon, we have been at the forefront of the profound changes that have influenced this century. Education and technology, though, have had a rocky relationship at best. We educators are often painted as stodgy worshippers of the past, asserting the consistent dominance of the older pen and paper over the pixel. Americans have been expecting technology to “revolutionize” the classroom for over a century. At least as early as Edison, we have also expected these technologies to radically alter our classrooms for the better.

Books will soon be obsolete in the public schools. Scholars will be instructed through the eyes. It is possible to teach every branch of human knowledge with the motion picture. Our school system will be completely changed inside of ten years.

July 1913, The New York Dramatic Mirror, Vol. 70, Issue 1803 (archive.org)

But the technology-as-educational-revolution narrative has been over-promising and under-delivering for much longer than a century. Yes, electricity profoundly altered our lives, and continues to do so as it powers almost all of the innovations that have come since, but what profound shifts did it bring to education? Most schools still meet during the day. HVAC was certainly an improvement over coal stoves or cross-breezes. But these transformations always fall short of the revolutionary human progress our tech-prophets have offered.

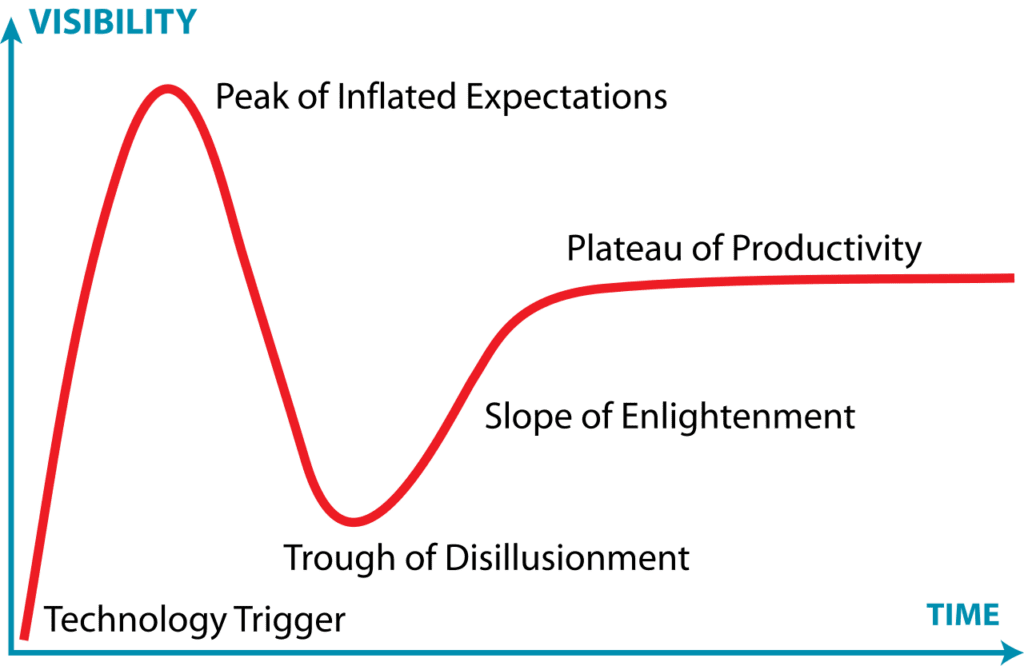

Generally, these technologies follow a pattern we can now see more clearly. As early as 1995, this pattern has been described as the “Gartner Hype Cycle.” When a technology is first introduced and improved rapidly in its early iterations, the trajectory of improvement is drawn up to infinity, and the tech-prophets promise to transcend the limits of human nature. Most people don’t necessarily believe all the hype, but there’s often so much of it, repeated so often, that it’s hard not to hear a ring of truth. As the irrational exuberance weakens, we notice the negative side effects, or the second and third-order effects. Thus, our love of a technology very quickly switches from prophecies of salvation to jeremiads against the permanent damage we’re inflicting on ourselves by adopting this technology. Things tend to level out, and we make peace with the tradeoffs inherent in each technology, only for the cycle to begin again when something new comes out. Optimism, Despair, Outrage, Apathy, but all without understanding. This trend maps to almost every technology since electricity, but we should try to stand outside the maelstrom and see clearly at each stage.

One problem with the Gartner framework is that it doesn’t always unfold temporally. People can criticize a technology after it’s been introduced, or even more strangely, before. Russell Kirk called cars “mechanical Jacobins” after most Americans had chosen not to live without at least one. TV was no longer young, and TikTok not yet invented, when Postman wrote Amusing Ourselves to Death (1985). Science fiction can critique a technology before it has arrived. Ray Bradbury critiques immersive entertainment in the novel Fahrenheit 451 (1953) and his short story “The Veldt” (1950). These extremes do remind one of Aristotle’s definition of virtue as the mean between two vices on the extremes. The truth, for most tools, often lies somewhere in the middle.

And so, I would encourage all of us to use a different critical lens for new technologies. First, it’s unlikely we’ll be able to convince a large chunk of our society not to adopt a given technology. We must first work within our circle of control and influence, which in general does not encompass all of society or even our entire school. Second, we should ignore the larger social “conversation” and be selective about who we listen to and how often. Overall, I want to find and listen to people who will explain one of two things to me about a new technology: how it works (its tendencies) and the effects we can foresee of handing this work to a tool (tradeoffs).

Plato pointed out that writing would weaken our memories (Phaedrus 275). This is a tradeoff most of us would immediately agree with, even if we’d never thought about it in those terms. Nevertheless, the upsides of writing mean that none of us will put away that tool anytime soon. We continue to encourage our students to read and write well, in spite of the tradeoffs. But a newer tool looms to replace the old tool. Perhaps one only needs to be able to write well enough to prompt AI and then—poof!— all one’s thoughts are clear, compelling, and quick. I’ve been trying to learn more about AI as I’ve used it myself and share what I learn with my students.

For AI, I think about the following tendencies and tradeoffs:

| Tendencies | Tradeoffs |

|---|---|

| Prediction based on statistical frequency in which characters occur together (Source: Colorado State University Global Blog) | Precise quotation of original sources is nearly impossible |

| 10x-60x more costly in terms of processing power/energy than a standard Google search (Source: Cal Newport, Deep Questions Podcast) | What is returned is based heavily on what is seeded and tends towards the lowest common denominator (i.e., the most common and least creative) way of combining ideas or answering questions. This saves on processing power and gives an answer least likely to offend (see third tendency) |

| Programmed to please the user (common sense) | Hallucinated results (i.e., false information) ensconced in flattering language |

What practical upshot has this meant for me? Well, I’m a high school teacher, and I’ve used AI to create or duplicate resources I use all the time like quizzes and tests. In general, it’s about 80% accurate for things I ask it to create in Latin, and a bit less so in Greek. I’ve spent the past two school years attempting to learn how to make ChatGPT a truly useful research assistant and idea generator. While it has not lived up to social hype or even my (rather sanguine) personal hopes for it, it is useful enough that I continue using it as a tool.

Most recently, I’ve folded AI into an essay I’ve assigned to my students. They’ve read a work in English, closely related to what we’re translating in class. I read the prompt aloud in class, and the first draft is written in one class period, with only the text on their desks to help them source direct evidence.Once they’ve finished their first drafts of the essay, I look them over to get a sense of two things: each student’s thesis and the support he musters in quotations from the source. They then take the essay home and have a couple days to type it up, hand it to an AI, and ask for criticism. They then copy the first draft, the prompt they gave the AI, and its feedback into a Google Doc that is shared with me. I then give more detailed feedback on the original essay as well as critique the AI’s feedback.

They are preparing their final drafts of these now, but I have taken a bit of class time the last couple weeks to highlight some of the helpful comments the AI gave them and some weaknesses of the rewrites or suggestions.

Seeming vs. Being

There is, of course, already the danger of having AI “help” them craft the essay. All in all, we have no perfect way to prevent our students from abusing this tool, as we had no perfect defenses against CliffsNotes, SparkNotes, or any other shortcut that has come before. Nevertheless, we must make clear to our students that this tool can be used or abused. We can, of course, also suggest it remain unused until they’re older.

Using AI as one interlocutor from whom you can request feedback is a valid use. Using AI to write for you is like hiring someone to go to the gym for you, or going yourself to watch others work out. This far into my experience with it, it writes to sound like someone else well, but struggles more with a precise analysis of the author’s original voice. Granted, I see this much more clearly in domains over which I have a high level of mastery relative to the general population (Latin and Greek), but even in English I can get Chat to *sound* like Charlotte Mason, but not to extract all the meaningful quotations on a given topic from her works themselves.

While it will always be fruitful to think with the older, and stronger, tools of pen and paper, it can be helpful to consult the oracle (as some friends say) for a second opinion, even if it will need to be amended or rejected. The exchange has still clarified my own thinking and hopefully will continue to do so.