If we were to take a survey of popular attitudes, I suspect most people would prefer to reduce their exposure to arguments rather than increase it. I’m very confident this would be true of people with teenagers in the household. So why do I teach a history course that claims in its title that arguments make history?

The short answer is that arguments are ubiquitous in human existence, and they are often pivotal in human history. We could not avoid them in daily life, not even in our marriages, without estranging ourselves from our families and friends. And we cannot avoid them in historical inquiry without estranging ourselves from the people and events we are trying to understand.

I do not lament these realities. I believe having arguments is better than not having arguments, despite the frequently negative connotations of the word “argument.” Furthermore, I value the craft of argumentation; I submit that it is possible to learn how to make good arguments (such things exist), and that arguing well is manifestly better than arguing badly.

Conflict and concord

Our somewhat paradoxical attitudes toward arguments stem from the very different connotations of the word in different contexts. To the extent we think of an “argument” as a verbal conflict, possibly even a shouting match, then most healthy people would rather skip it. But arguments, even in this negative, conflict-focused sense, are an unavoidable consequence of our human freedom. Life presents us with many choices, not just as individuals but as groups and even as nations. Arguments occur when reasonable minds differ about what path to take, or how to proceed down that path, or who should lead. If we value the freedom to make those choices, we can hardly bemoan the conflicting opinions that freedom generates.

Indeed, many of the important turning points in history can be, and perhaps should be, understood primarily as arguments in this sense. “Mr. Gorbachev: Tear down this wall!” That’s part of a relatively recent argument between the free world and the communist world, and the outcome changed day-to-day life for hundreds of millions of people. We can be glad that argument is over without regretting that we had it.

Or this:

With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan.

That’s a nineteenth-century argument that has echoed so loudly down the years that we built a secular temple to the memory of its author and literally carved the words in marble.

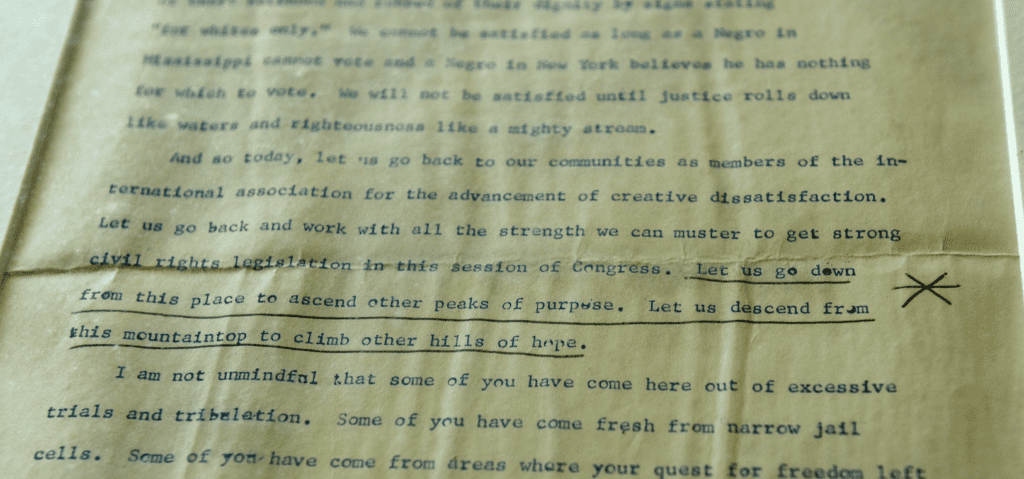

Or how about this one:

I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all men are created equal.’

That’s a twentieth-century argument quoting an eighteenth-century argument. It was a brilliant collaboration across the centuries by two men who never met and who were widely separated not just by time but by circumstance—yet look what it produced. Each of those men has taken his place in our secular pantheon, with good reason.

Sometimes the historical conflicts that generate such great arguments may be latent; the people locked in the argument may not even understand the ways their views have been shaped by images from their past, or by popular trends of which they are not yet conscious. They only know that they are at some fork in the road, some moment of decision. If we want to understand those forks in the road better, we can make an excellent start by attending to the way people argued about them at the time.

And this brings us to the more positive connotation of the word “argument.” It is striking how commonly our best leaders help us define and achieve social goals not with force or even mere authority but rather with reason—with arguments. We might think it unfortunate for Smith and Jones to be in conflict about anything, but if they are in conflict it is surely better for them to settle it with arguments founded on reason and morality than with brute force. Swap out “Smith and Jones” in that sentence for “Britain and her colonies,” “North and South,” “blacks and whites,” or “Catholics and Protestants,” and this becomes a point of no small significance. It is when we are in the midst of big and ugly arguments that we are most in need of great and beautiful arguments.

Rhetoric and history

Crafting great arguments is hard work. It requires sound logic, of course, but that’s not nearly enough. The great arguments also require rhetorical technique—the self-conscious use of linguistic patterns and devices that have worked across different cultures and languages for at least three millennia. There is a legend that the Gettysburg Address is short because Lincoln scribbled it on the back of an envelope while he was traveling to Gettysburg on the train; or in some versions, while the speaker who preceded him was droning on interminably. The story is provably false—we have the drafts from before Lincoln was in Gettysburg. But even without the hard evidence, the story is absurd to anyone who appreciates the rhetorical sophistication of the speech as it was given. The Gettysburg Address abounds with unmistakable echoes of what Pericles had said on a similar occasion twenty-five centuries earlier; there are themes of death and rebirth skillfully woven throughout the speech; a single word, “dedication,” is used in three different ways to unify three very different purposes Lincoln sought to achieve. None of that was an accident. I do not deny that some people just “have a way with words,” nor that Lincoln was such a person, but speeches like that are not jotted hastily on envelopes.

Is there more to say about the rhetoric than that it is lovely or stirring or persuasive? I think so, and the people who crafted the arguments thought so. Lincoln did not begin the Gettysburg Address with “Four score and seven years ago” because he thought that was the clearest way to count to 87; he was deliberately using Biblically resonant words. We have three score and ten years to a normal life in Psalm 90; three score and ten palm trees at Elim in Exodus 15. And so at Gettysburg with hundreds and perhaps thousands of the dead still lying around unburied, Lincoln uses “four score and seven” to elevate the discussion instantly to a plane far above the battlefield where he spoke.

We can think of this rhetorical craftsmanship as a giant spotlight on the speaker’s primary purposes. John F. Kennedy, in his Inaugural Address of 1961, said the mundane things in mundane ways, but he reserved the classical rhetorical device of chiasmus for the point that came to define his entire administration in the historical consciousness of a generation:

ask not what your country can do for you;

ask what you can do for your country.

We can’t ask Lincoln or Kennedy what their main points were, but we don’t have to, because their rhetorical choices already revealed the answer for all time.

Rhetorical choices also include choices about what not to say. When Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. chose to say, “I have a dream,” he was choosing not to say, “I have a complaint”—which he certainly could have said. When Abraham Lincoln chose to say that we should take care of the widows and orphans on both sides of the Civil War—“with malice toward none, and with charity for all”—he was choosing not to say that he would make those misbegotten rebels curse the day they were born. To notice this is to know their minds, long after their deaths.

The recovery of historical context

One of the greatest obstacles to historical understanding is presentism, the tendency to interpret events from the past as they were happening in the present. At The Heights, we try to rely heavily on primary sources—documents that provide direct, first-hand evidence of historical events because they are part of what actually happened rather than a later interpretation of what happened. This can really help us to understand historical actors on their own terms.

But it doesn’t do much good to use a primary source unless we do the work to understand that source in its original context. And when we read a primary source for the first time, we’re not always sure what to do with it. In fact, with primary sources, we’re supposed to have questions. Can we trust this source? Are there biases of which we should be aware? Is there another side? If we skip these questions and take everything at face value, we’re not doing it right.

I offer students an acronym to suggest a few of the questions we should routinely ask. It’s corny, but those are the most memorable acronyms. It’s SPEQRS. (We pronounce it “speakers”—get it?)

- S is for Setting. Where was this argument originally advanced? Was it a speech or an essay? (In a few cases, the answer is “both.”) Who was the intended audience? Was there a special occasion (say, a funeral, or a murder trial) that would necessarily shape the discussion and place constraints or demands on the speaker?

- P is for People. Who is advancing this argument? What do we know about the person and his or her prior history before this moment? Who are the other significant parties to the controversy—the other characters in the drama, so to speak? Do they come from parties or communities whose particular interests are part of the story?

- E is for Events. We don’t need to know much about the Peloponnesian War to understand Pericles’ Funeral Oration, but we should know something. And we should know a lot about the Kansas-Nebraska Act and the Dred Scott decision if we want to understand Lincoln’s “House Divided” speech. We want to be familiar with the events that were on the minds of the speaker and the other participants so we can enter into conversation with them.

- Q is for Questions. What are the principal questions the speaker tries to address—the main points of the argument? We haven’t really read the argument very carefully unless we could close the book and describe to a friend what conclusion(s) the speaker wanted the audience to reach and why. (We may have additional questions that we ask with historical hindsight, but let’s start with the speaker’s questions.)

- R is for Rhetoric. How is the speaker trying to persuade? Is the rhetorical style plain or highfalutin? Is it primarily factual? Emotional? Philosophical? Legalistic? How much of the speaker’s own persona is invested in the argument? Does it “work” rhetorically? Where are the rhetorical high points, and what do they tell us about the speaker’s purposes?

- S is for Sequelae. Okay, I had to reach for this one, but sequelae are later events, things that happened after the argument in question, and usually either because of it or in spite of it. That is, arguments “make history” not just in the sense that history remembers them, but also in the sense that they produce the decisions and events of which history consists. If we’re inclined to think an argument is unimportant, it’s often because we haven’t spent enough time thinking about the sequelae.

So, as much as our polarized public discourse might lead us to shy away from arguments in everyday life, the study of history is much richer with arguments than without them.