Without some prior wonder at creation as the declaration of its Author, and therefore as an intelligible reality that corresponds to minds because it is a product of Mind, all philosophy collapses into skepticism.

—Sebastian Morello’s Mysticism, Magic, and Monasteries: Recovering the Sacred Mystery at the Heart of Reality

Last year, my wife and I moved to a small Maryland town not too far from our Potomac campus. The house we bought was formerly a two-room public school house in Montgomery County, built in 1899. I’ve met a few neighbors who told me that their mother or father was a student in the school, which closed in 1939, and was sold by the town in 1943 to a private individual before undergoing remodeling to make it a more spacious family home.

The original school house had a coal burning stove as its sole heat source, with coal bins below the front steps. Two outhouses—presumably one for girls, one for boys—were out back. When we moved in, we had some of the chimney rebuilt and the firebox replaced. The slab in front was cracked, and so that too was taken out and a new one installed. Only this summer did I learn that the slab might have been from the chalkboard of the original school. I would have still replaced it, but would have hung on to part of it as a souvenir of the house’s earlier life.

What stories that slate likely held within its sooty depths! Children from my town—most didn’t go to college, many were from farm families—first walked into this school on the eve of a new and momentous century. Later students experienced world wars, and the lean years of the Great Depression. While those times surely were dramatic or just plain difficult, the slower pace of communication in those days must have left many rural towns enclosed in the quiet of a daily existence they had always known.

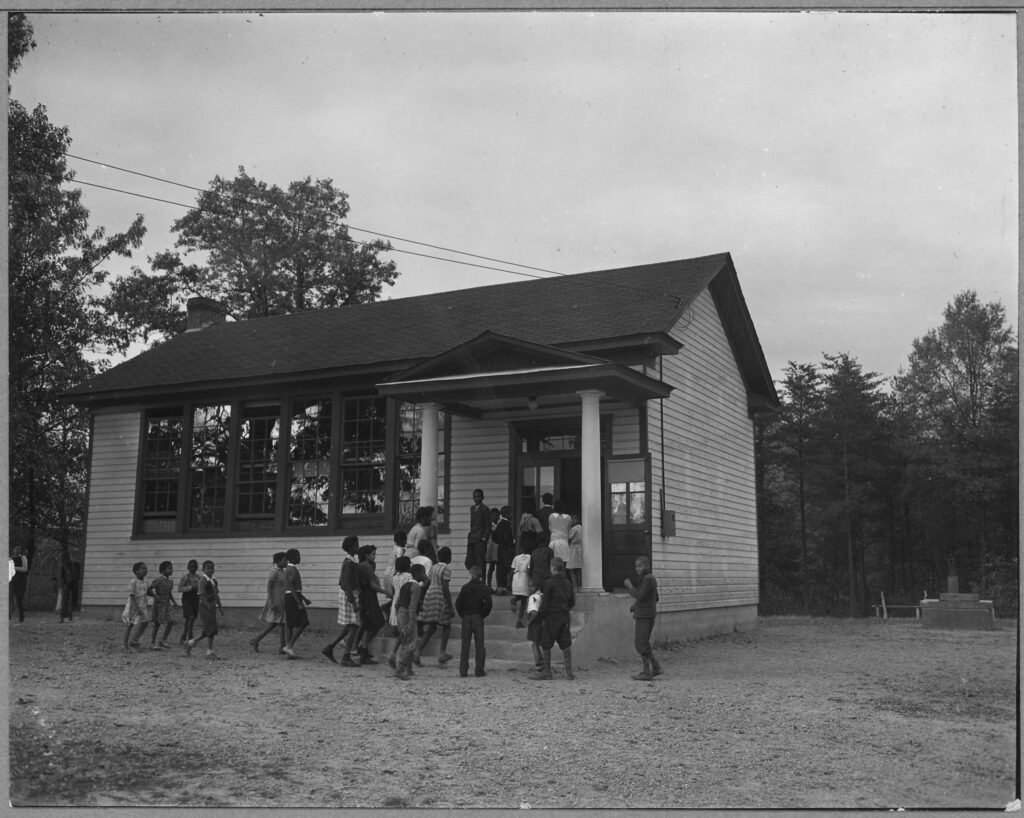

The Schoolhouse in the US

At the start of the twentieth-century, some estimates put the number of one-room schoolhouses in the United States at 200,000. Today, only about 12,000 remain standing as private residences, museums, banks, or sheds put to use on a farm. In Montgomery County, there are 34 former schoolhouses. The small schoolhouse, with 25 students and one teacher, was largely standardized out of existence as counties grew in population and wealth. In Montgomery County, the oldest standing one-room school is the Seneca Schoolhouse, built in 1866 from the same sandstone quarry that supplied the stone for the Smithsonian Castle in Washington, DC.

I have tried to lay my hands on a published study of Maryland schools in the year 1899, but it’s been hard to locate or purchase. Calvert County’s numbers from this volume were available online: there were 47 schoolhouses in the county; 6 male teachers or principals; 44 female teachers; subjects included bookkeeping, algebra, physiology (the most popular by number), geometry, philosophy, and Latin (the least popular by number). Although the ratio of white to black students was about 1:1, the spending for black students was a 1/3 of the monies spent on white students. More than half of these children worked on the family farm or business, so bookkeeping and physiology are certainly understandable favorites.

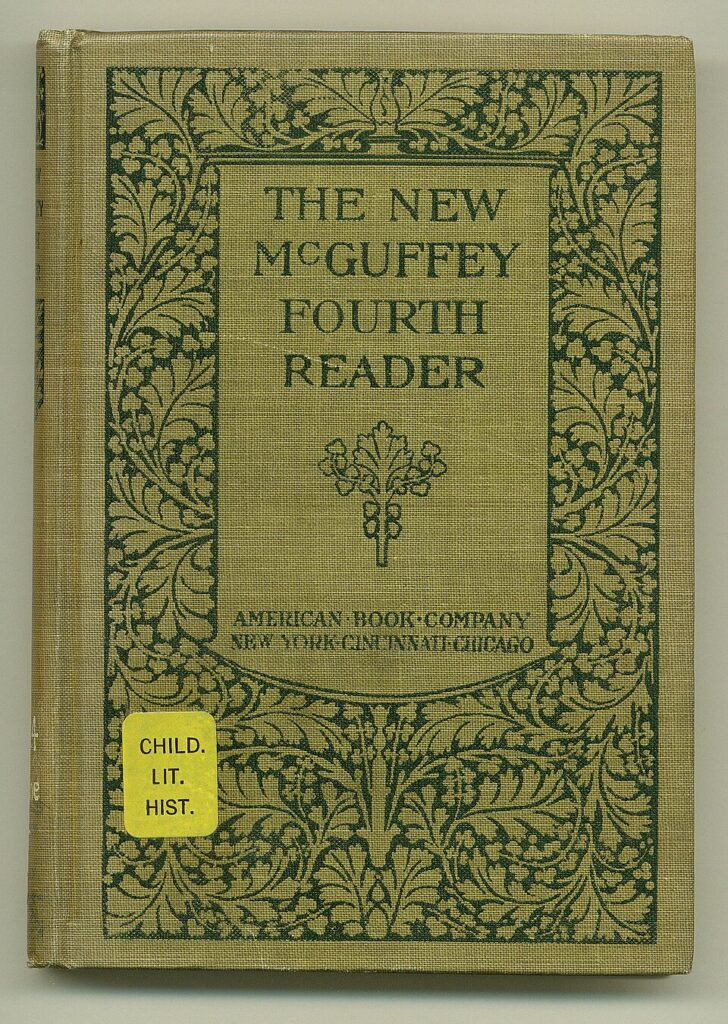

I have an obvious interest in the reading and writing curricula of these years. As many know, the McGuffey reader for grades 1-6 is pretty solid ballast for any child’s early years in school. Much was left to the teacher to bring to life the hundreds of excerpts from writers such as Longfellow, Thoreau, Whittier, Hawthorne, Irving, Dickens, and Tennyson. In the 6th year came excerpts from Hamlet and Charles Lamb’s deliciously sly “Dissertation on a Roast Pig.” The latter’s long paragraphs are broken down to smaller ones, but the wit and the wisdom of the piece are intact—for 12-year-olds. Yet we should remember: though the curriculum by our standards was solid and demanding, the delinquency rate of students in the late 19th and early 20th century was high: only in the 1930’s did students on average complete 150 or so days out of 175, numbers roughly comparable to schools today. Before that, say in 1900, the average number of days per year attended by students in the United States was in the low 90s. The demands of farm-life, alongside the poor state of medicine took their toll. Life in those days had limitations and sufferings we would find intolerable in our time. But is that all they had? I wonder.

Life in the Schoolhouse

We know from weather records that 1899 was memorably cold: the low that winter was minus 24 degrees in Garrett County, some ways from Montgomery County, but you get the idea. The roads were not paved in the small towns (paving began up county in 1910, at MD 118, in Germantown, with a macadam road), so walking to school in the winter months, even just a few miles, meant trudging through snow, mire, and horse droppings, getting by slippery bridges, fording frigid streams. The wind off the acres and acres of farmland cut at your face, prowled through your jacket and scarf, numbed your fingers through mittens your sister knit for you till it reached your core and tried to snuff it out. School didn’t start until around eight or nine in the morning, so at least you were spared walking in the predawn darkness.

Many schoolhouses didn’t have much natural light as windows might distract students with their view. You can actually see this idea built into the structures of the schools: windows tended to be built with the lower sill a little higher than three feet from the floor precisely to avoid distracted young eyes from gazing outside, away from their books. Those old-fashioned stoves could crank out the heat, so it’s likely that the school was blessedly warm when you walked in from the arctic streets. The schoolhouse held about 15-25 students; older ones sat in the back, sometimes helping the teacher with tutoring the younger students.

As your eyes stopped watering from the cold, and you started feeling your fingers again, waves of heat emanating from the central stove thawed out your brain. Wood cracked and snapped; coals seethed in the wind running up the flue. So went the day, scrolling across the hours as many a school day did before it. If you had to answer the call of nature, you went to the outhouse, whatever the weather. During lessons, there was the sound of scraping chalk, choral recitations, spelling bees, even speeches written and addressed to the class from the slightly taller landing where the teacher sat behind his or her desk.

Along with these inconveniences there were attractive elements too: the smell of hickory or oak burning in the stoves, the gratitude at not mucking out a barn on one of the coldest days in recent memory, the daily miracles of warmth in the ever-surrounding icy grip of winter. In 1899, there was an embeddedness in the material world for most people that surely spoke many wonders. Little of their comfort was abstract, especially when a teacher asked a student to go fetch a bucket of coal or a bundle of wood for the next few hours of warmth. If he refused—well, he wouldn’t, because freezing to death in school is a particularly unpleasant way to leave this life.

Lessons from the Schoolhouse

I read a substack column now and then by Ryan B. Anderson who writes about life on his family farm in Vermont. His handle on X is “Old Hollow Tree.” Anderson writes with grace and beauty of life with his honey bees, chickens, and his growing number of children. He’ll write whole essays brimming with observation and wisdom on the Milkweed. He seems to get with clarity elements of healthy family life that are also founding principles of life in a school that truly serves the human person.

Here’s how Ryan puts it, after reflecting he might not have cut enough wood to keep his family warm until spring: “As I shut the cellar door, I reflect on how we see people flocking to the natural world these days in spite—or perhaps because—of its harsh truths. The modern world allows us to avoid so much consequence, to be so unaccountable to what truly matters. The natural world offers a refuge from this strange inverse: a proportional, inexorable, and unyielding consequence for all things. Despite how grim and dire this sounds, make no mistake: we hunger for it. We need it now more than ever.” Fortunately, he had a reserve of oil in his basement to turn on the furnace if he ran out of wood, but the principle stands.

How right that it should. Just because we can deny consequences of our actions doesn’t mean there aren’t any. This principle of being accountable, of teaching ourselves and our family (and students) that magical thinking is no friend to our happiness in this life or the next, is essential to keeping the hearth flame, as it were, lit for our families and schools. Truth, being, the real: this gives light and warmth to the relationships in which we live.

This tangible encounter with what is comes to us in our childhood and, ideally, into our youth, giving us a taste for the real in our experiences of the wonderful (and sometimes dangerous) ways of nature. We learn in our finger tips the warmth of an open fire—and not to touch the hot grate with our hands. We learn in the smell of freshly baked bread or biscuits the love our mothers have for us. We learn in the providential thinking of our fathers (in their care for little things, in their planning for larger things, however imperfectly) of the universal and individual providence of God for the world and ourselves. A half-century later, I can still remember the clean smell of cut lumber, the orderly arrangement of tools, in my best friend’s garage. His father was a carpenter who knew how to take care of things.

The folks of the one-room schoolhouse were well aware of the necessities of life. Conveniences in their time were rare. Dinner would not arrive at the click of a keyboard. So when the real work of acquiring the basics of life was finished—for the day, at least—they could reach for the superfluous, in the best sense of the word: those overflowing natural gifts of higher culture—poetry, story, music, the musings of history. These treasures are won with some effort but more readily appreciated, perhaps, for what they are when seen in the uncompromising clarity of a society that doesn’t worship convenience. Did they reach for the higher things unfailingly? Of course not. But the texture of their lives led them towards the humanities in ways our culture—more fittingly called, at times, an anti-culture—does not.

Those natural gifts were themselves, on a human plane, transforming. The key is to avoid two opposing errors: letting ease and comfort deafen us to the calls of higher culture, and mistaking that higher culture for moral or religious virtue.

Our life, warmed by the fire of earthly loves, is meant for something infinitely higher. When a family or school forgets this, the light of grace can grow dim precisely while earthly goals are reached and even surpassed. Pelagianism—the idea that we can reach salvation without grace—may yield the most impressive practical results of any heresy, and yet it is perhaps the most damning. When we don’t make idols of cultural or professional achievement, we fortify ourselves against the fruitless task of trying to make finite goods yield infinite returns. That’s a fool’s game, in a Biblical and even worldly sense.

The key is to avoid two opposing errors: letting ease and comfort deafen us to the calls of higher culture, and mistaking that higher culture for moral or religious virtue.

With the right perspective, however, these earthly loves of culture can yield opportunities for grace precisely because they in some way dimly foreshadow divinization—becoming a child of God—by reminding us how even our humanity is a process of transformation to higher things, especially a refined articulation of our search for God, the basis of every true culture.

Preserving the Memory

In remembering these old-fashioned schoolhouses, let’s try to remember that limitations aren’t always bad, for they can be instructive in their demands on our character and imagination. They can shake us out of our abstracted experience of almost everything. These communities of simple schoolhouses now long gone knew that a school is so much more than its curriculum. It’s not that curriculum isn’t important; it’s that there is a whole pedagogy of the real that needs to prepare us for reception of the treasures of higher education, whether in the humanities or the sciences. (This is also true of the Faith, which is more than a set of intellectual propositions.) Such a pedagogy should induce wonder and reverence before the world which comes from God, that “infinite sea of being,” in the words of Dante.

In his fascinating book cited at the opening of this essay, Sebastian Morello reminds us that we in post-modernity often labor under delusions that drain the world of its wonder. To free one’s self from this is to see a world porous to transcendence, where the light of rationality inscribed in being yields the wonders of science as well as the raptures of the mystic.

So we should gather solid fuel for the hearth of our own families, chiefly by prayer. But also by watching in wonder bats skirt over a field on a summer night, or by figuring how to bake (no precision, no dessert), or by seeing bulbs bloom in our garden that we planted in the previous year, or just by learning to build a proper blaze in the fireplace. Teaching a youngster how to distinguish different trees for firewood, and how to handle an axe so he can chop some wood, can do wonders for appreciating, in our very limbs, where the warmth and the gifts of life find their source. Gift and effort, after all, are two essential poles of every life that flourishes.